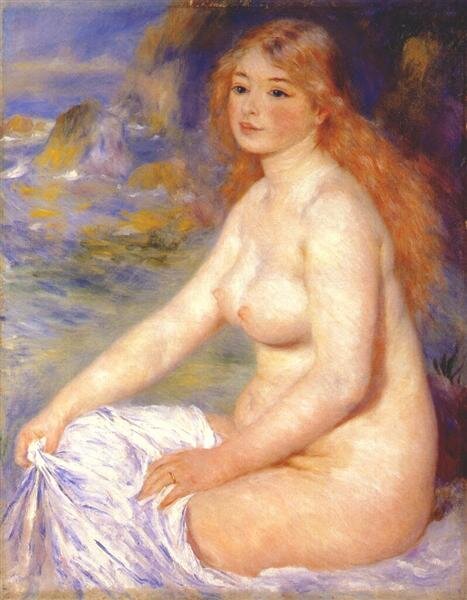

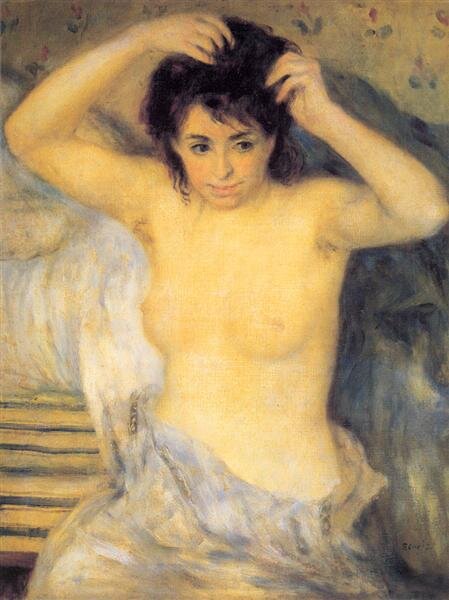

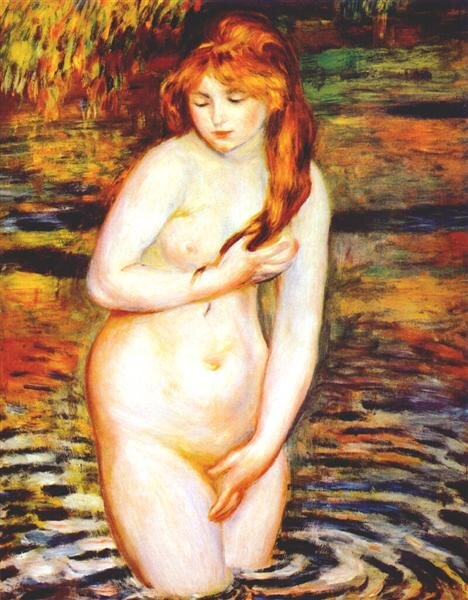

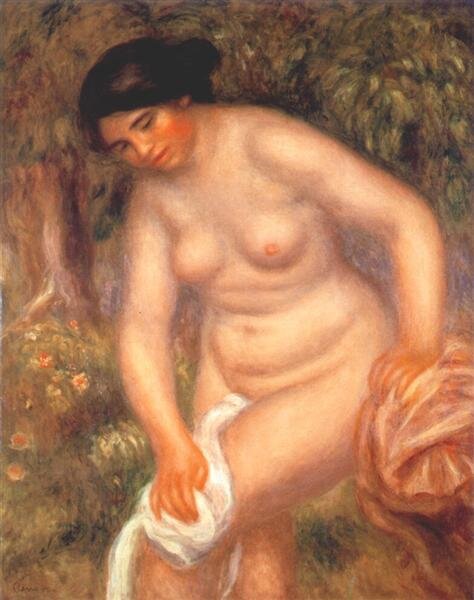

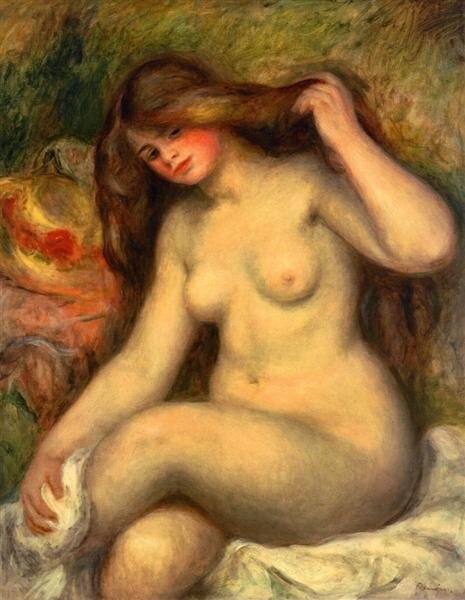

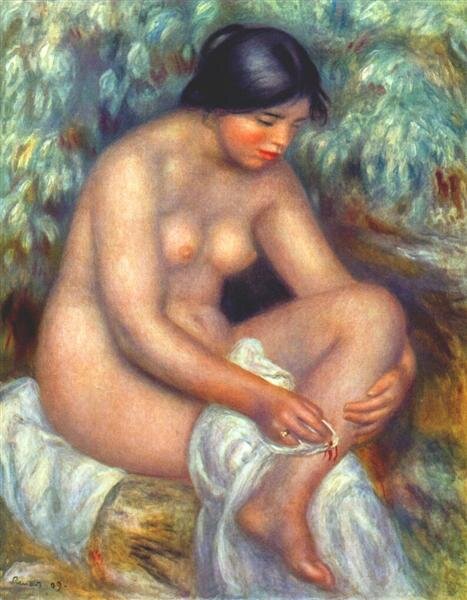

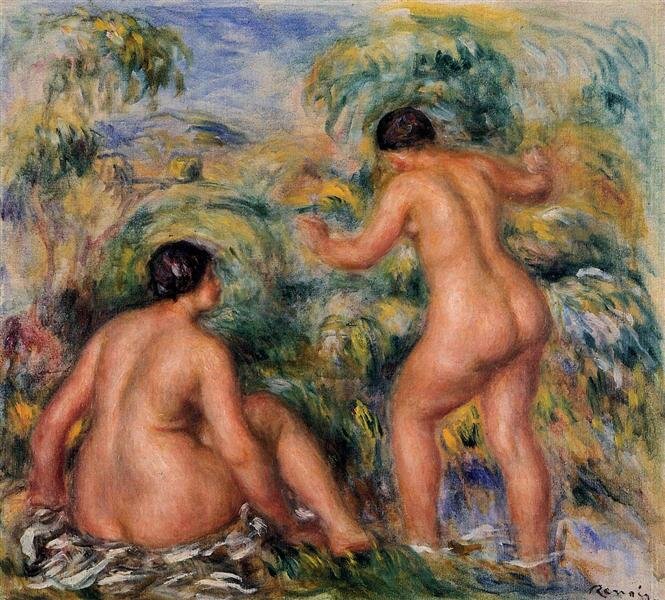

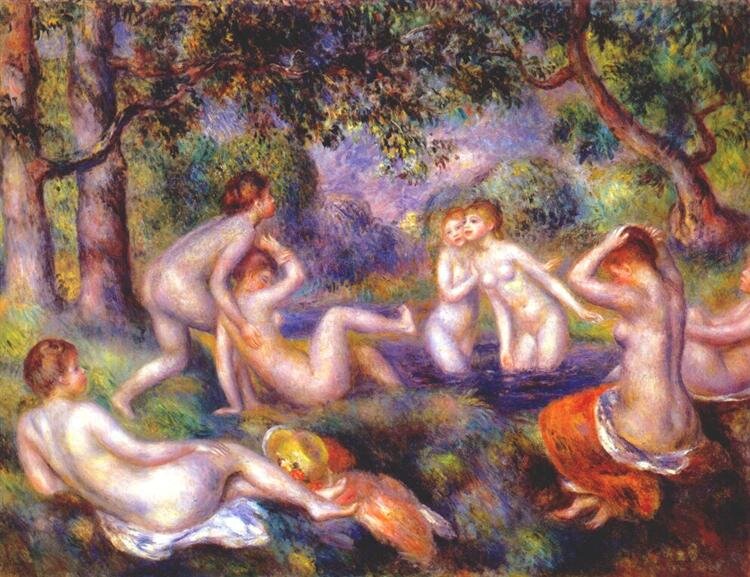

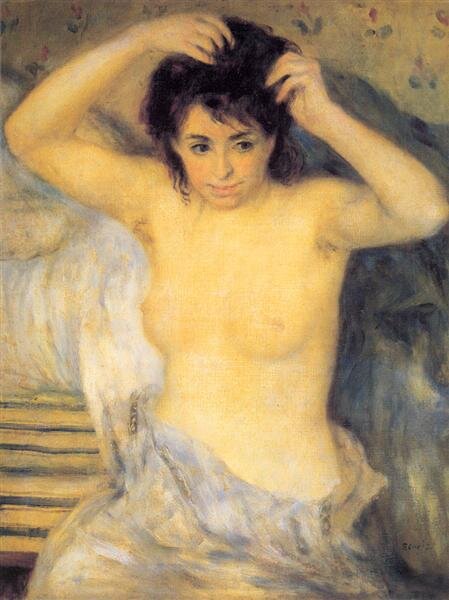

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

1875

Impressionism

Barnes Foundation, Lower Merion, PA, US

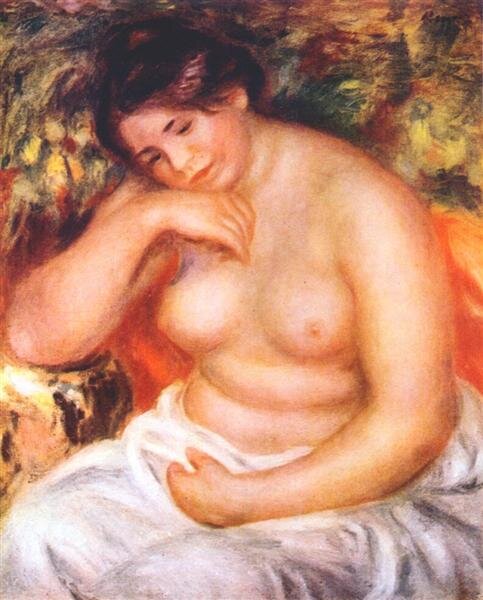

Musee des Beaux Arts de Montreal

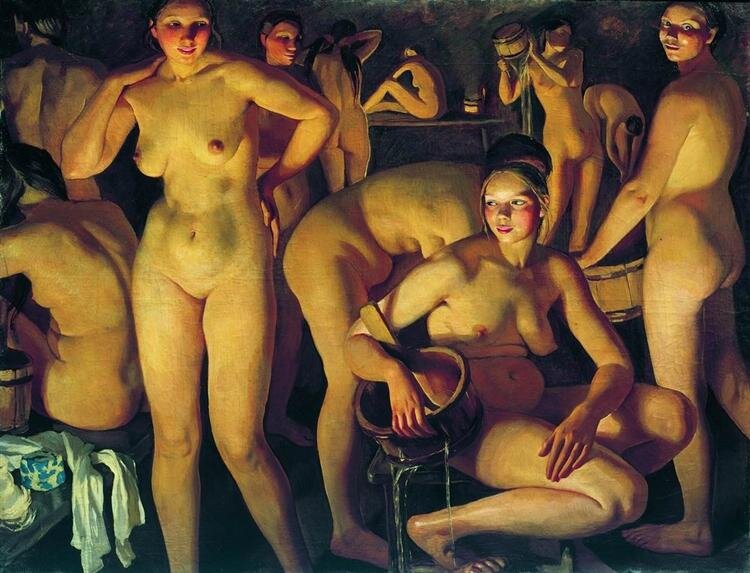

Wilhelm Lehmbruck

Duisburg, Germany, 1881– Berlin 1919

1914

Cast stone

93 x 46 x 45 cm

Purchase, inv. 1949.1023

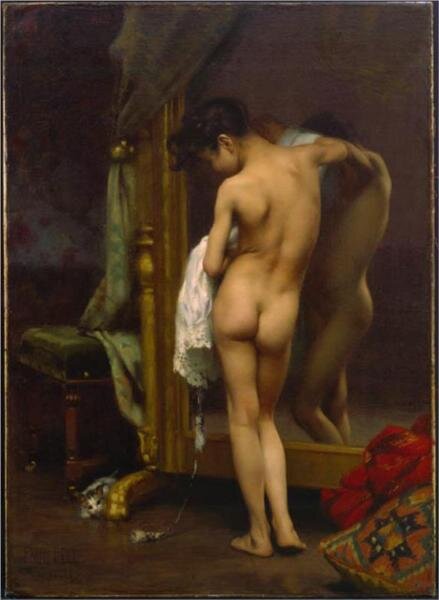

Lehmbruck lived from 1910 to 1914 in Paris, but ultimately returned to his native country, where he died an untimely death. The young generation of sculptors strove to forget Rodin by returning to the simplified, solid and measured volumes of antique statuary. This Bathing Woman evokes the classicism of the Greco-Roman Venus Pudica, a figure portrayed modestly covering her nudity. Though influenced by the French sculptor Maillol, Lehmbruck developed a personal style characterized by elegantly elongated forms described at the time as “gothic,” softened by a sfumato-like treatment of the smooth surfaces. The unusual use of cement, or “cast stone,” can be explained by Lehmbruck’s contact with other foreign artists living in Montparnasse, such as Brancusi and Archipenko. By opting pragmatically for this material—less expensive than marble or bronze, but more solid than plaster or terra cotta—they were able to produce low-cost editions in a distinctly modern manner.

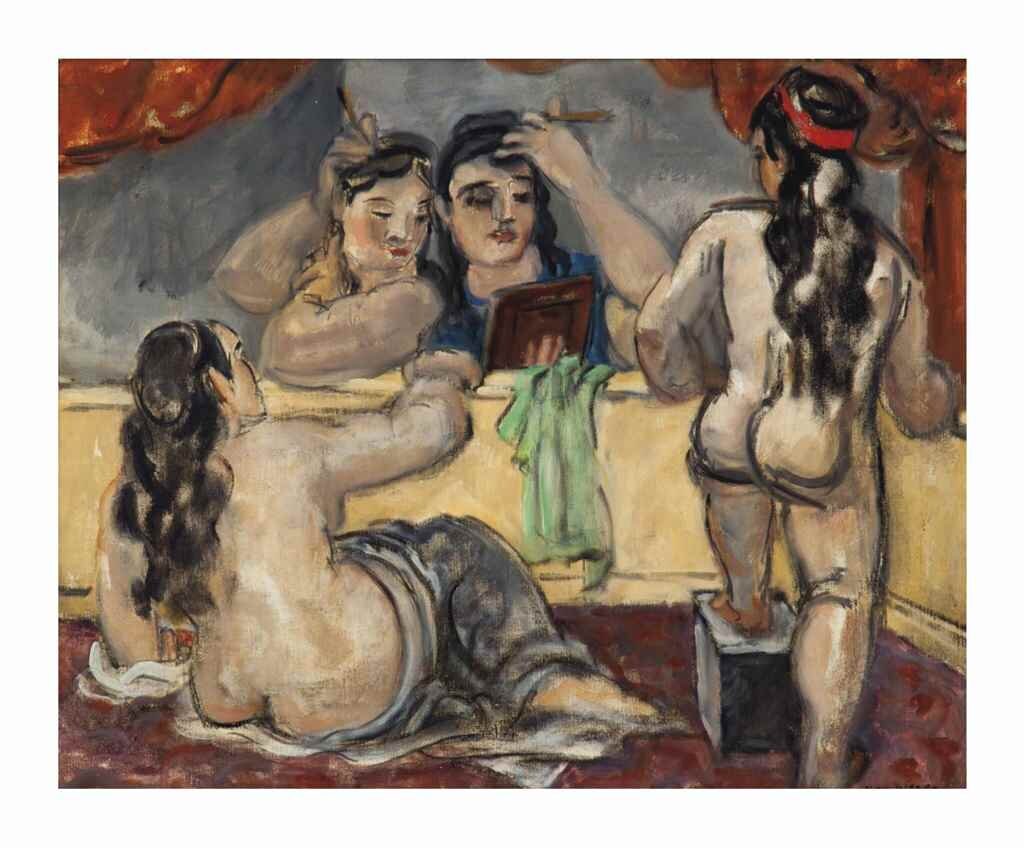

Eugene Delacroiz

1821-1822

Romanticism

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA, US

Rineke Dijkstra, 1993, Chromogenic print, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Purchased with funds contributed by the Photography Committee, 1998

Rineke Dijkstra is first and foremost a portraitist. Specifically, she documents individuals caught in transitional states of being: mothers just after giving birth; preadolescent bathers poised on various beaches in the United States and Eastern Europe; club kids just off the dance floor in England and the Netherlands; teenage soldiers in Israel. Formally, her comparative series resemble classical portraiture—frontally posed figures isolated against minimal backgrounds—and in some sense follow in the tradition of August Sander, the early- and mid-twentieth-century chronicler of occupational typologies in Germany. In contrast to Sander who sought to fix and identify social types—the baker, the bricklayer, the peasant—Dijkstra searches for glimmers of individuality among like types—a hair out of place, a bead of sweat on the brow, an uneven stance. The uniformity within each series is disrupted by the sitter’s emotional and physical particularities, which often expressly communicate a tension heightened by his or her shifting state.

Although she isolates the bathers in her Beaches series (1992–96) and frames them with only sea and sky, Dijkstra reveals much about them by capturing a subtle gesture or expression in these unguarded moments that reside somewhere between the posed and the natural. The end result is a collaboration between sitter and photographer, a record, however partial, of their interaction. In photographing the already awkward young subjects in their bathing suits, Dijkstra sets up a situation marked by exposure and self-consciousness that parallels the uneasy passage between childhood and adulthood. The images represent individuals from various countries and, as a whole, add up to a meditation on adolescent disconcertment. The photograph is the ideal medium for Dijkstra’s practice precisely because of its explicit suspension of the movement of time: like Dijkstra’s subjects, photographs are always between one moment and another.”

Thomas Hart Benton, 1938, 20th Century

Oil and Tempera on Canvas mounted on Panel

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

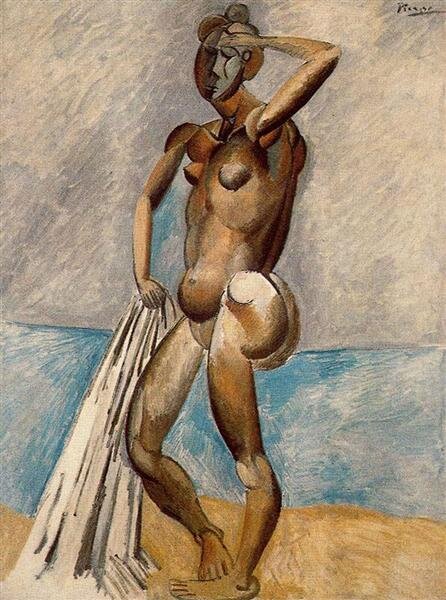

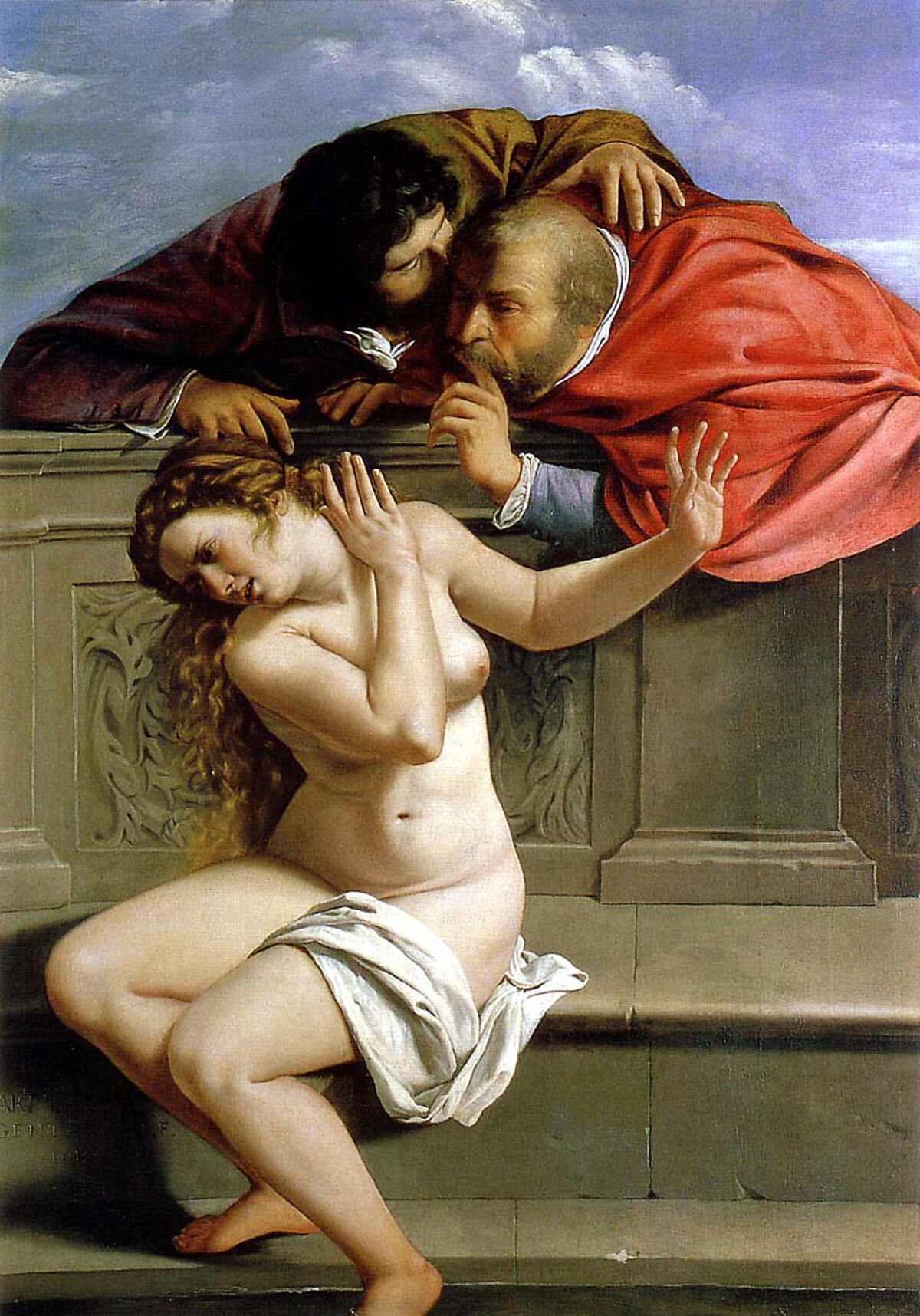

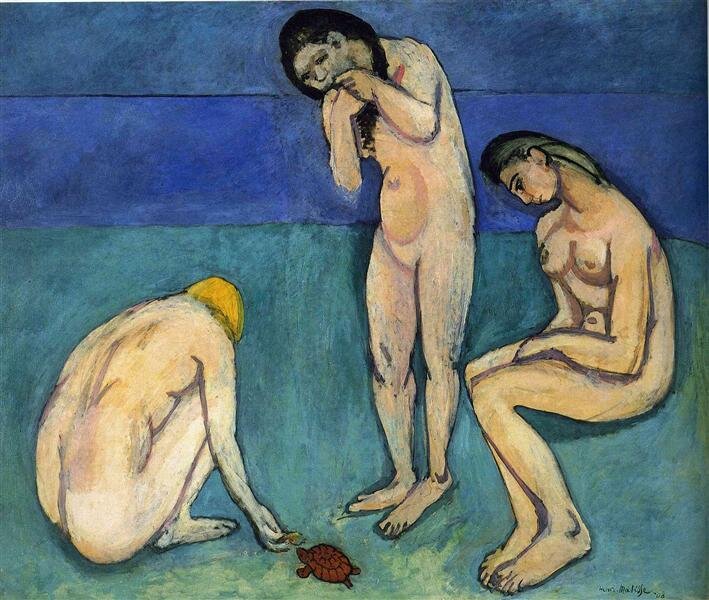

Pablo Picasso, 1937, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 1976

"During the early months of 1937 Pablo Picasso was responding powerfully to the Spanish Civil War with the preparatory drawings for Guernica and with etchings such as The Dream and Lie of Franco, an example of which is in the Peggy Guggenheim Collection. However, in this period he also executed a group of works that do not betray this preoccupation with political events. The subject of On the Beach, also known as Girls with a Toy Boat, specifically recalls Picasso’s Three Bathers of 1920. Painted at Le Tremblay-sur-Mauldre near Versailles, On the Beach is one of several paintings in which he returns to the ossified, volumetric forms in beach environments that appeared in his works of the late 1920s and early 1930s. On the Beach can be compared with Henri Matisse’s Le Luxe, II, ca. 1907–08, in its simplified, planar style and in the poses of the foreground figures. It is plausible that the arcadian themes of his friendly rival Matisse would appeal to Picasso as an alternative to the violent images of war he was conceiving at the time.

At least two preparatory drawings have been identified for this work. In one (Collection Musée Picasso, Paris), the male figure looming on the horizon has a sinister appearance. In the other drawing (present whereabouts unknown),¹ as in the finished version, his mien is softened and neutralized to correspond with the features of the two female figures. The sense of impotent voyeurism conveyed as he gazes at the fertile, exaggeratedly sexual “girls” calls to mind the myth of Diana caught unaware at her bath."

Lucy Flint

Pablo Picasso: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Thannhauser Collection, Gift, Justin K. Thannhauser, 1978

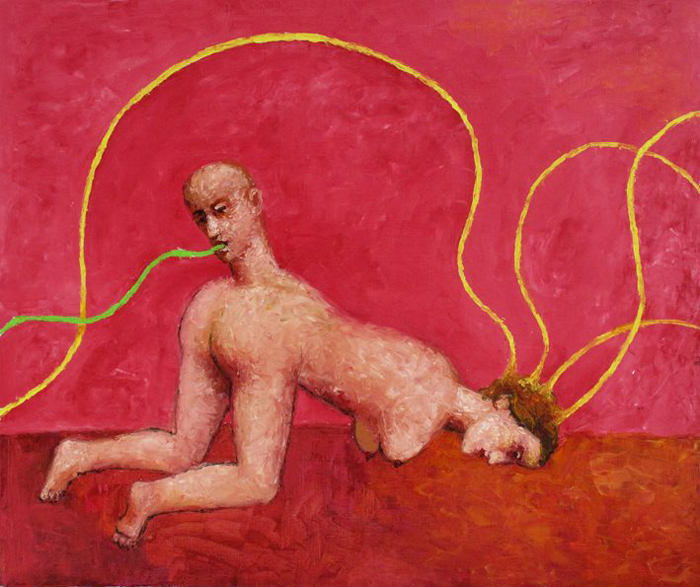

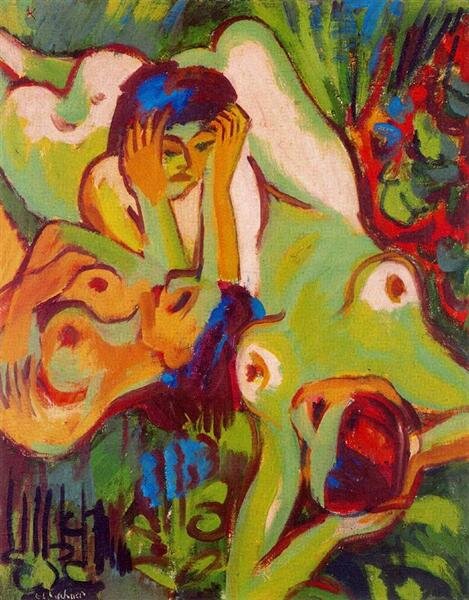

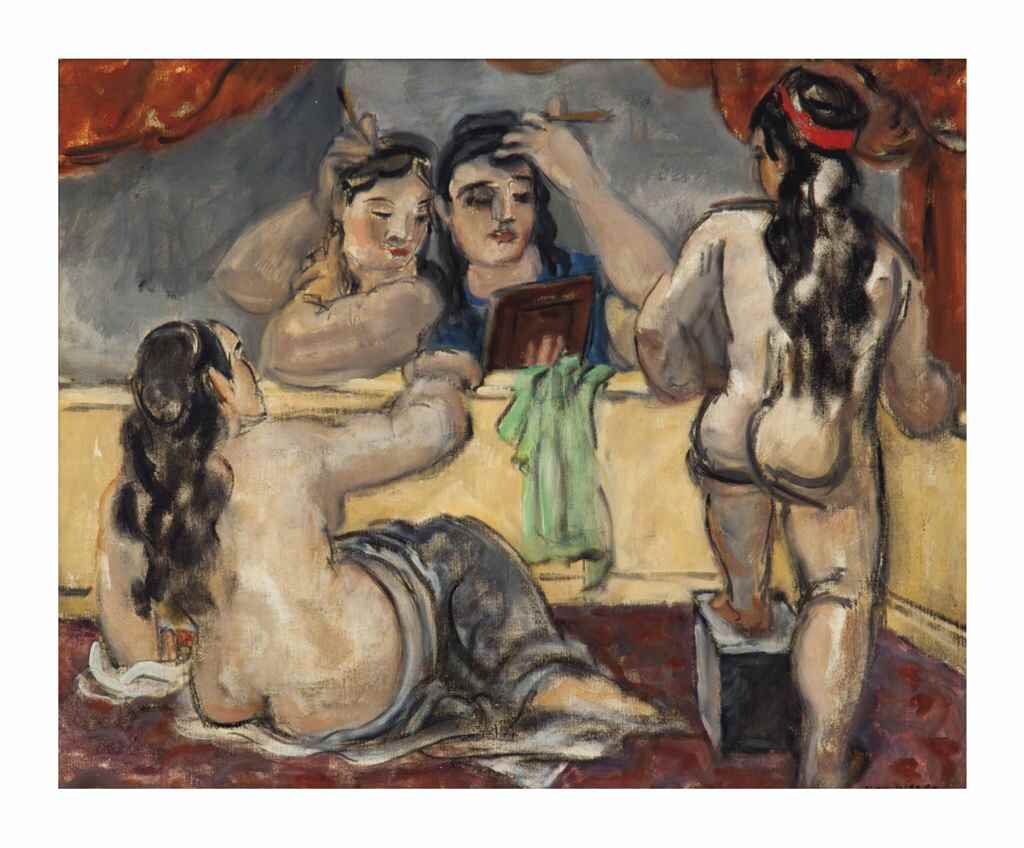

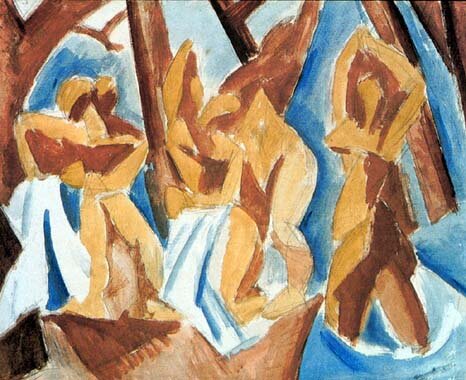

"After World War I, a number of artists active in the international avant-garde (including French painters André Derain, Fernand Léger, and Henri Matisse, as well as Italians Giorgio de Chirico and Gino Severini) turned to classicism as a source for form and content. This reinterpretation of classical imagery has been described as a search for tranquility in a world destabilized by the carnage of war and the socioeconomic upheaval caused by mass industrialization. The informal name for this period, the Return to Order, comes from French poet Jean Cocteau’s book Le rappel à l’ordre (1926), in which he discussed these developments.

One of Pablo Picasso’s early classicizing works is Olga Picasso in an Armchair (Portrait d’Olga dans un fauteuil, 1917), an oil painting of his future wife, a dancer with the Ballets Russes, in a style inspired by the work of 19th-century neoclassicist Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres. In Picasso’s static and calm composition, the figure is elegantly and ideally proportioned. Before long, however, the artist subverted his own placid style with works such as Three Bathers (Trois baigneuses, August 1920), in which he created what might at first seem like an Arcadian idyll, until one notices that the bodies of the languishing nudes are distorted. A gigantic hand and swollen arm cradle the too-small head of the reclining figure in the foreground, while the arms and legs of the seated nude are impossibly long relative to her head and torso. With these enlargements and attenuations, Picasso combined classical symmetry with its opposite, the grotesque. The liberties with form are magnified by the amount of space they take—nearly the entire width and height of the picture—and their placement against three bands of almost entirely unmodulated color meant to stand for blanket, water, and sky. The insertion of such inflated forms into a shallow space conveys a monumentality of scale, regardless of the dimensions of the work itself." — Robin Clark

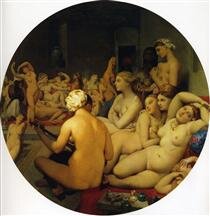

Paul Gauguin (1848–1903): Metropolitan Museum of Art, Manhattan, New York City