The FEMME FATALE

Click on links below to jump down to each section

Medusa | Women & Snakes | Cleopatra | Eve | Prudence | Venus | Helen | Desdemona | Calypso | Circe | Delilah | Pandora | Lilith | Medea | Jael | Judith | Clytemnestra | Salammbô | Salome | Omphale | Deianira | Esther | Potiphar’s Wife | sirens | vampires | evil | witch

The idea of the femme fatale and other treacherous women has fascinated writers and artists for centuries.

This likely stems from and feeds into a general fear of women (whether conscious or subconscious) and a resulting justification for oppressing them.

My research explores how we see women depicted in art and how this relates to how women are treated today.

This research in turn informs my artistic practice.

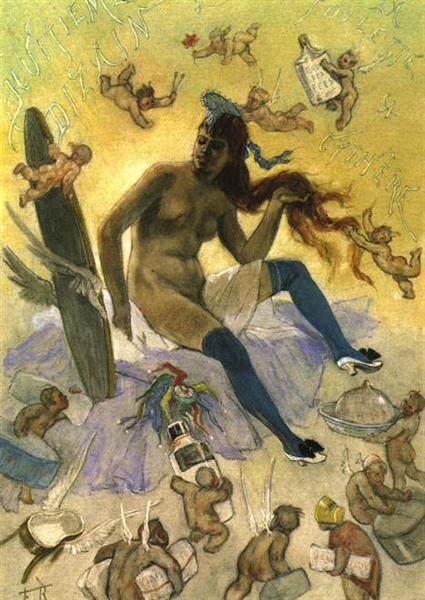

“The femme fatale is often called a seductress, temptress, sorceress, and is compared to such biblical personae as Eve, Lilith, Salome, Delilah, Judith, and Jezebel; and mythological figures such as Medea, Medusa, Circe, and Clytemnestra. Real or fictional women of power, such as Cleopatra and Salammbô are another type of the femme fatale. Monstrous seductresses, a further variant of the femme fatale, are represented as vampire and siren personified.”

Medusa

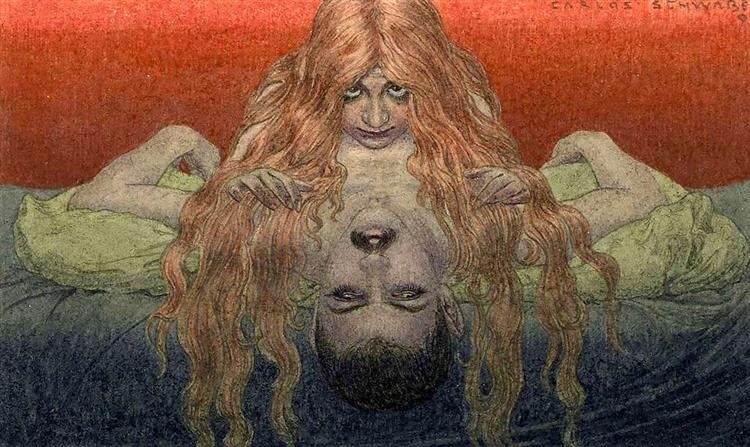

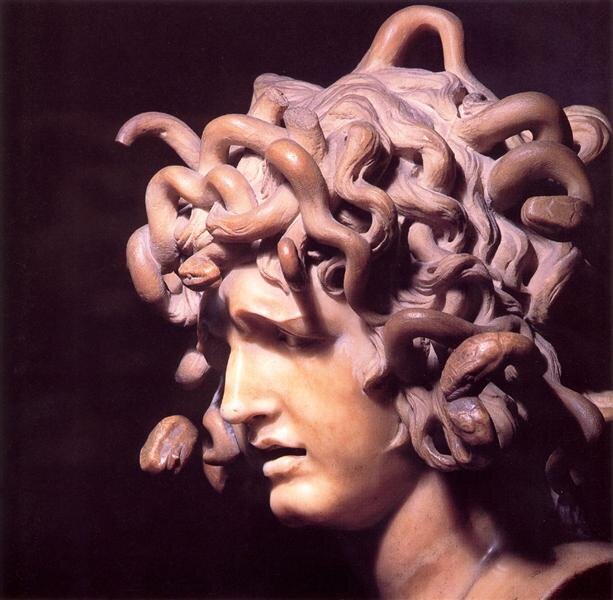

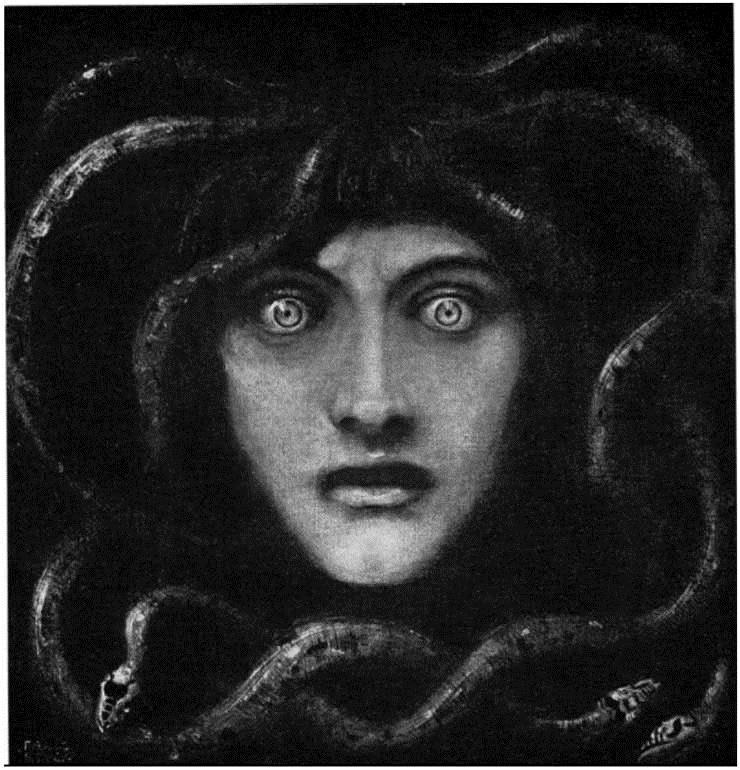

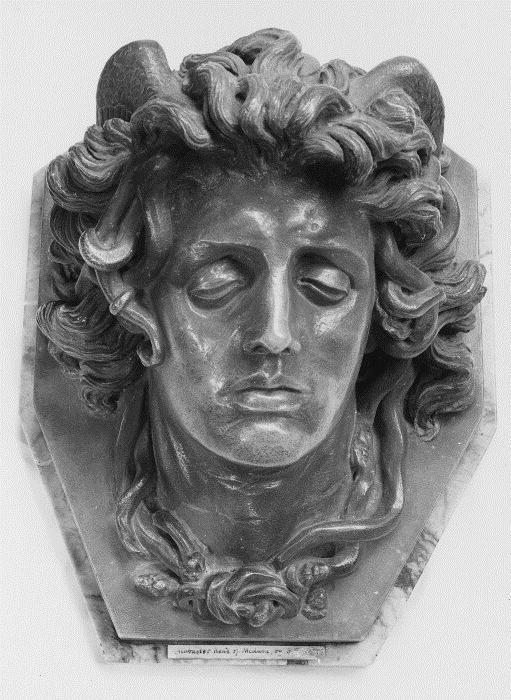

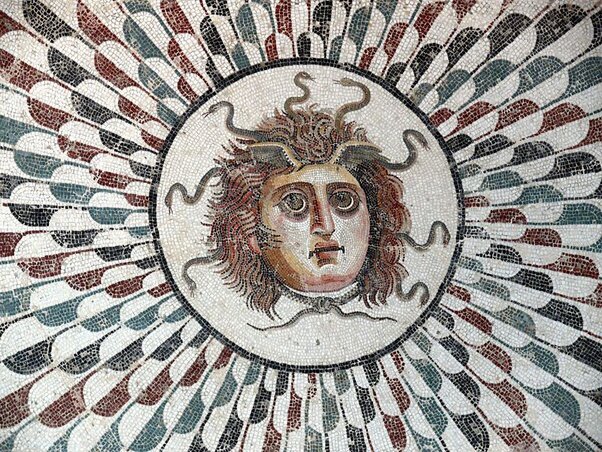

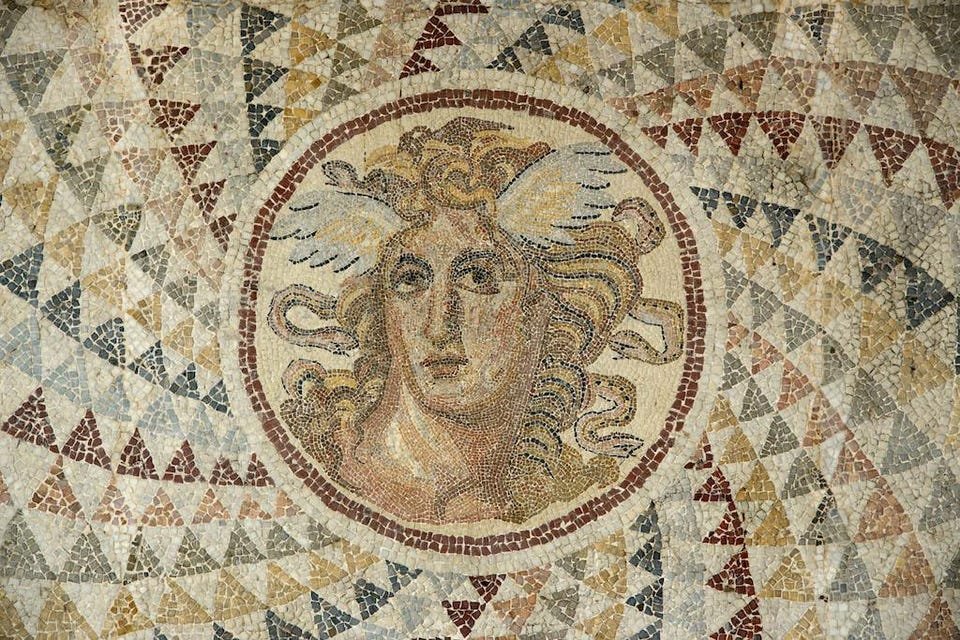

Medusa has a bad rap. She is the archetypal wronged woman of Greek mythology. Also known as the archetypal “angry woman”, Medusa has been adopted as a symbol of female rage, and the personification of female fury.

Many only know her as a hideous female monster with snakes for hair whose fury and frightful eyes will turn viewers to stone if they so much as glance at her. But Medusa was not just a Gorgon monster. She was a beautiful woman, who was raped (or sexually active); then blamed for being raped (or for engaging in sex); then transformed into a raging monster, banished from her homeland and subsequently beheaded.

“Medusa remains the symbol of the quintessential nasty woman that must be vanquished in order to restore the balance of power.”

Today Medusa evokes the idea of a woman with a terrifying potential power to emasculate men. Almost every strong woman, particularly those running for or achieving political office or fame, has been equated Medusa or photoshopped with snakes for hair, including: Marie Antoinette, Hilary Clinton, Angela Merkel, Theresa May, Condoleezza Rice, Madonna, Nancy Pelosi, Oprah Winfrey, Rihanna and Elizabeth Warren. The face of Medusa appears in paintings and sculptures throughout history; in literature, film and theatre; on boats and buildings; on housewares; and even as a logo by the fashion company Versace.

Torn from her spiritual path, raped, blamed, banished and ultimately beheaded — Medusa’s story echoes that of countless women throughout history. While her monstrous rage and debilitating grief petrifies all who look upon her, viewing Medusa is possible via mirror. Eyeing this ancient wild/wise woman requires facing our own fears, culpability and difficult questions — so we may recognize and stop perpetuating toxic beliefs and behaviours. Medusa's story has inspired a number of paintings in my installation Eyeing Medusa. Ultimately I believe that Eyeing Medusa can shift perspectives and change historically toxic narratives by focusing on respect, empowerment and self-actualization.

The oldest existing version of the story of Medusa comes from the poem Theogonia, composed circa the eighth century BCE by the Greek poet Hesiodos of Askre. Here, Hesiodos mentions that Medusa was the only mortal of three sisters, daughters of the ancient marine deities Phorcys and Ceto, chthonic monsters from the archaic world. In this version she is born a Gorgon with the ability to turn people to stone at a glance. She may also, according to some depictions, have had the body of a horse. Hesiodos writes: “With her lay the Dark-haired One [i.e., Neptune/Poseidon] in a soft meadow amid spring flowers.” Since Hesiodos makes no mention of this being a rape, we may understand that she was a willing partner in sexual activity. She was, however, still cursed and punished as a result.

In Ovid’s narrative poem The Metamorphoses, it is told that Medusa was the only mortal of three sisters (Medusa, Stheno and Euryale) known as the Gorgons. These sisters were also sisters of the Graeae: Deino, Pemphredo and Enyo — old women, grey ones, grey witches — who shared one eye and one tooth between them. However, being mortal, Medusa was also distinguished from them by the fact that she alone was born with a beautiful face. Ovid especially praises the glory of her hair, “most wonderful of all her charms.”

Medusa was one of the sacred priestesses serving in the Temple of Athena. Some say she had many suitors but had chosen not to marry in order to devote herself to her work. Medusa was lovely, and she knew it. Some suggest that her beauty rivalled that of Athena, but that soon changed. Was Athena jealous of Medusa?

One day her beauty caught the eye of the sea god Poseidon, who becomes enamoured with the lovely girl. Determined to have her at any cost, he rapes her in the sacred temple of Athena.

Furious at the desecration of her temple, Athena transforms Medusa into a monster with a face so hideous and a gaze so piercing that the mere sight of her is sufficient to turn a man to stone. Medusa’s enchanting hair is transformed into a coil of writing serpents; and she is banished to a remote and foreign land.

Soon after this, Polydectes, the king of Seriphos, sends Perseus on a quest to bring back the head of Medusa. (The king fully expects and hopes that Perseus will be unsuccessful because he wants to marry Perseus’ mother, Danaë, and requires her son be otherwise occupied.) Aided by Hermes and Athena, Perseus pressed the Graeae, sisters of the Gorgons, into helping him by seizing the one eye and one tooth that the sisters shared and not returning them until they divulged Medusa’s whereabouts, and provided him with winged sandals (which enabled him to fly), the cap of Hades (which conferred invisibility), a curved sword, or sickle, to decapitate Medusa, and a bag in which to conceal the head. Perseus finally reaches the fabled land of the Gorgons, located either in the far west, beyond the outer Ocean, or in the midst of it, on the rocky island of Sarpedon.

Creeping up on Medusa while she is asleep — using the reflection in Athena’s bronze shield as a guide so as to not look directly at Medusa and be turned into stone — Perseus decapitates Medusa with his sickle. At the time of her death Medusa was pregnant by Poseidon. The assassination of Medusa releases her two unborn children Chrysaor and Pegasus (the winged horse) from her severed neck. The resulting noise awakens the Gorgon sisters who endeavour to avenge Medusa’s death but they are unsuccessful because Perseus is wearing Hades’ Cap of Invisibility and Hermes’ winged sandals. Returning to their cave the sisters mourn their fallen sister. Hearing their gloomy lament it is said that Athena modelled the music of the double pipe, the aulos, after the sound.

On the way back to Seriphos, flying across northwest Africa, Perseus stops briefly in Ethiopia. There, he rescues and weds his future wife, the lovely princess Andromeda who he found naked and chained to a rock on the shore. (Save that for another story). The corals of the Red Sea were said to have been formed as Medusa's blood spilled onto seaweed when Perseus laid down her severed head beside the shore — attending to Andromeda’s rescue. Later as Perseus flies across the sands of Libya, with Medusa’s putrefying head clutched in his hands, the falling drops of her blood create a race of poisonous vipers of the Sahara; and also spawn the Amphisbaena (a horned dragon-like creature with a snake-headed tail). And that is why that, to this day, Libya abounds with serpents. Perseus then flew to Seriphos, where his mother was being forced into marriage with the king, Polydectes.

Perseus used Medusa’s head to turn him and various other vicious islanders into stone — which explains why the island became famous for its many rocks. Perseus then gave Medusa's head to Athena, who placed it on her shield, known as the Aegis. Athena also collected some of the remaining blood and gives most of it to Asclepius, who used the blood from Medusa’s left side to take people’s lives and the blood from her right side to raise people from the dead. The rest of Medusa’s blood – a vial containing two drops – Athena gave to her adopted son, Erichthonius; Euripides says that one of the drops was a cure-all, and the other one a deadly poison. She also put aside, in a bronze jar, a lock of Medusa’s hair for Heracles, who subsequently gave it to Cepheus’ daughter, Sterope, to use to protect her hometown Tegea. Although the lock of hair lacked the power of Medusa’s gaze, it could still cast terror into any enemy unfortunate enough to behold it, accidentally or otherwise.

Women & Snakes

“The snake is life force, a seminal symbol, epitome of the worship of life on this earth. It is not the body of the snake that was sacred, but the energy exuded by this spiralling or coiling creature which transcends its boundaries and influences the surrounding world. [. . .] Its seasonal renewal in sloughing off its old skin and hibernating made it a symbol of the continuity of life and of the link with the underworld.”

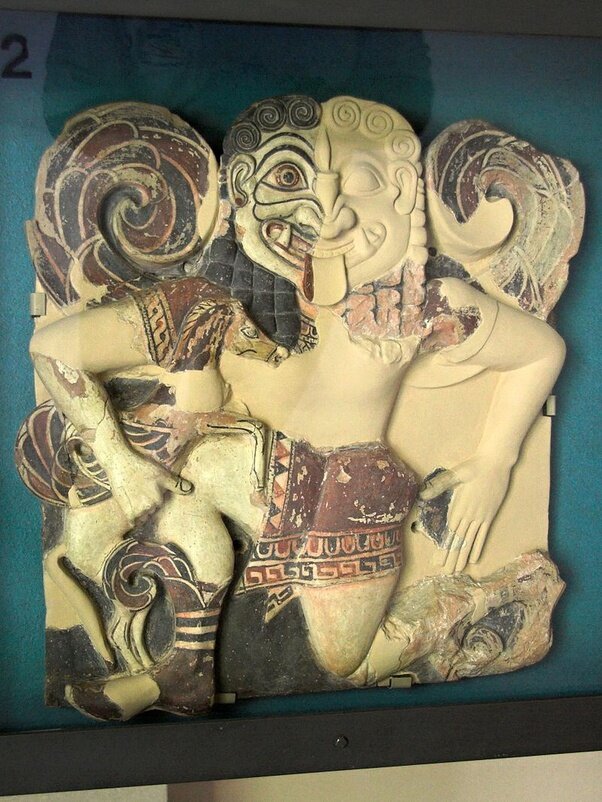

The Gorgon was a protective deity from the ancient world. The power of a Gorgon was so strong that one would be turned to stone upon daring to gaze at her. A Gorgon wore a belt of serpents that intertwined as a clasp. Such images were therefore used for protection and put upon a range of items, including armour, shields, temples and wine vessels.

An archaic Gorgon (circa 580 BC), as depicted on a pediment from the temple of Artemis in Corfu, Archaeological Museum of Corfu

Detail from Alexander and Bucephalus - Battle of Issus mosaic - Museo Archeologico Nazionale - Naples. Image courtesy of Wikipedia

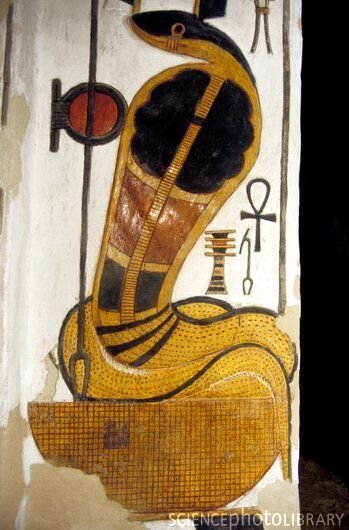

Medusa’s origins may be rooted in the Egyptian Cobra Goddess Wadjet. Greek historian Herodotos of Halikarnassos (c. 484 – c. 425 BCE) wrote in Histories 2.91 that Medusa and her sisters lived in the land of Libya, which, for the ancient Greeks, meant the whole part of North Africa west of Egypt. Depicted as a snake-headed woman or a cobra she was associated with the land as matron and protector of Egypt; of kings and of women in childbirth. As the nurse of the infant God Horus, Wadjet was closely associated with the Eye of Ra. The word “Egypt” comes from the Greek word for “Black”, referring to the Black Nile, but possibly also referring to the people. Her serpentine hair may have been dreadlocs.

The Cobra Goddess Ua Zit was revered on the Nile Delta in pre-dynastic Egypt as the Uraeus serpent, the Eye, featured on the foreheads of Egyptian deities and royalty. This Egyptian serpent goddess is also known as Buto, Uto, Wadjet, Wedjat, or Bast — worshipped in Lower Egypt, usually portrayed as a woman or a cobra wearing the crown of lower Egypt. She was also associated with images of Au Set (Isis) and may have been connected to the Sumerian belief in Ama Usum Gal Ana, Great Mother Serpent of Heaven. She may also have survived in the Arabian Goddess Al Uzza who was regarded as either Venus or Sirius.

The most sacred centre of the worship of Ua Zit was the Delta town of Per Buto (the Greek Buto), said to lie beneath modern day Dessuk. Buto was regarded as one of the most important oracle sites of Egypt at the time of Classical Greece. The placement of the Ua Zit Cobra on the forehead is comparable to the Indian concept of the Shakti Kundalini serpent rising to the Ajna Chakra, considered the Third Eye of Wisdom.

Closely associated with Horus the Elder, and the counterpart to the Upper Egyptian Goddess Nekhbet, Ua Zit/Wedjat was called “Lady of Heaven” and “Queen of all Gods”. She is depicted as either carrying a papyrus stem around which a cobra was coiled, or as simply as a cobra coiled in a basket wearing the crown of Lower Egypt. She is also called “the Lady of the Flames, and considered a protector goddess because she spits out her venom against the enemies of the king. She was depicted either as a cobra or snake with a woman’s torso; or as a woman with a snake’s head, a two-headed snake, or a woman wearing the uraeus. Wadjet was associated with the Milky Way–the primal serpent. In later dynasties she was elided with the goddess Bast, combining the attributes of a lion and a cobra.

“The etymology behind the word “venomous” explains the relationship between women and snakes, coming from the Latin venenatus, “furnished with poison, poisonous, venomous” or “imbued with magical powers.” Thus, the snake imagery depicts the capability of a woman unleashing her venom, her magical powers, and striking those holding her captive. ”

Python was a Greek serpent goddess, daughter of Gaea, who guarded the oracle of Delphi on Mount Parnassus until she was slain by Apollo who claimed the oracle as his own.

“The shrine that perhaps offers the deepest insight into the connections of the female deity of Greece to the Serpent Goddess of Crete is Delphi. [...] In the earliest times, the Goddess at Delphi was held sacred as the one who supplied the divine revelations spoken by the priestesses who served Her. The woman who brought forth the oracles of divine wisdom was called the Pythia. Coiled about the tripod stool upon which she sat was a snake known as Python ... described in the earliest accounts as female [. . . ]

It was the priestesses who most often supplied the respected counsel.”

The caduceus, two serpents entwined around an axial rod carried by Hermes, is considered the symbol of human consciousness.

The caduceus first appeared as a symbol of God Ningishzida, c 2100 BCE, a Mesopotamian underworld deity considered to be the god or goddess of medicine, nature and fertility.

Medusa may also have derived from the Minoan Snake Goddess.

The Caduceus, symbol of God Ningishzida, on the libation vase of Sumerian ruler Gudea, circa 2100 BCE.

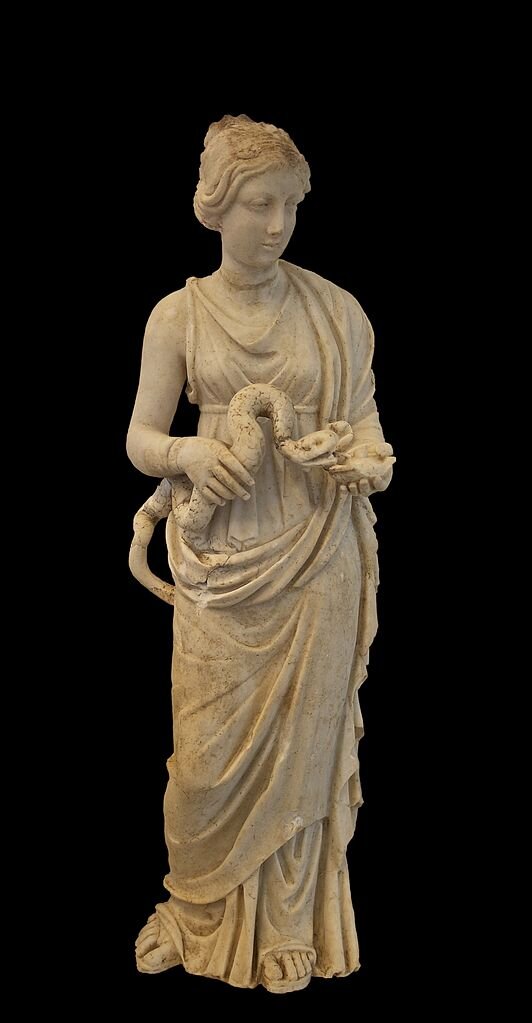

Hygieia is the Greek Goddess of Health, Cleanliness and Sanitation. She was the daughter or wife of Asclepius, the God of Healing and Medicine. Hygieia is often depicted as a young woman feeding a large snake which is wrapped around her body or drinking from a jar she carries. The Bowl of Hygieia is one of the symbols of pharmacy, as is the Rod of Asclepius depicted as a rod with a snake entwined around it.

What caused the snake to morph from a symbol of sacred life energy into the symbol of evil? When did the snake first come to represent evil?

CLEOPATRA

Cleopatra was an Egyptian queen, (70/69 BCE - 30 BCE) famed in European history and drama as the lover of Julias Caesar and later as the wife of Mark Antony. She became queen on the death of her father, Ptolemy XII (51 BCE) and ruled first with her brother Ptolemy XIII and then with her brother Ptolemy XIV, then with her son Ptolemy XV Caesar. In the battle of Actium, Octavian (the future Roman emperor Augustus) waged war upon Egypt, defeating Antony and Cleopatra, who then committed suicide and Egypt fell under Roman domination. Cleopatra actively influenced Roman politics and has come to represent the prototype of the femme fatale. Given that the symbol of a snake featured prominently upon the headdress of the Egyptian pharaoh and that the Romans were appalled at the idea of a female leader, as Cleopatra might have become had she and Antony been successful — could this be one of the origins of the idea of the snake being seen as a symbol of evil?

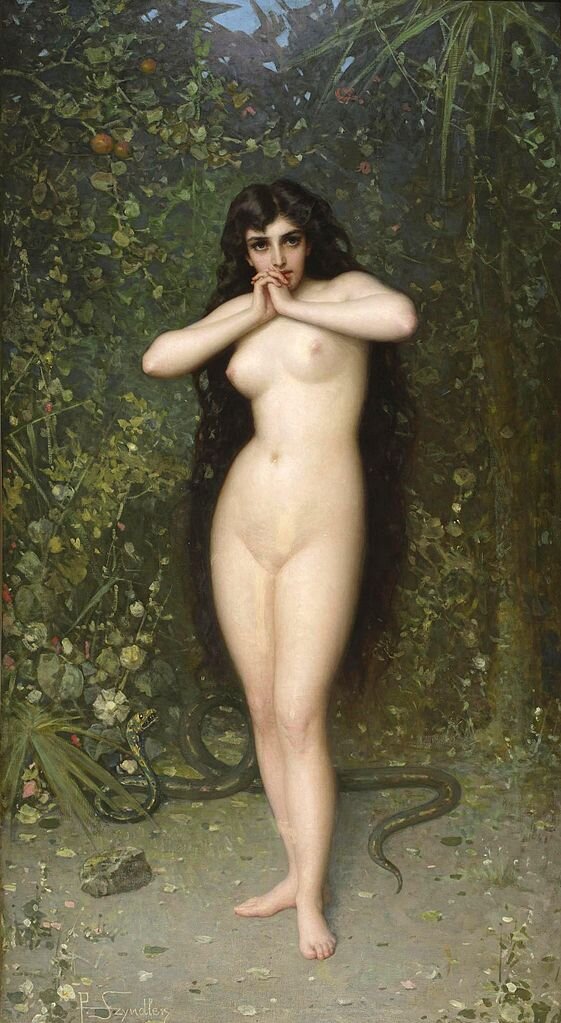

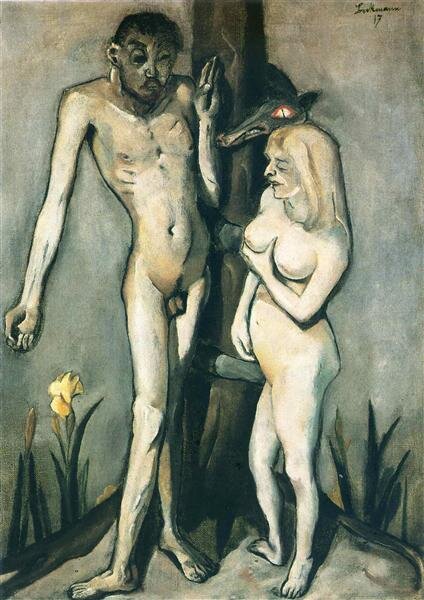

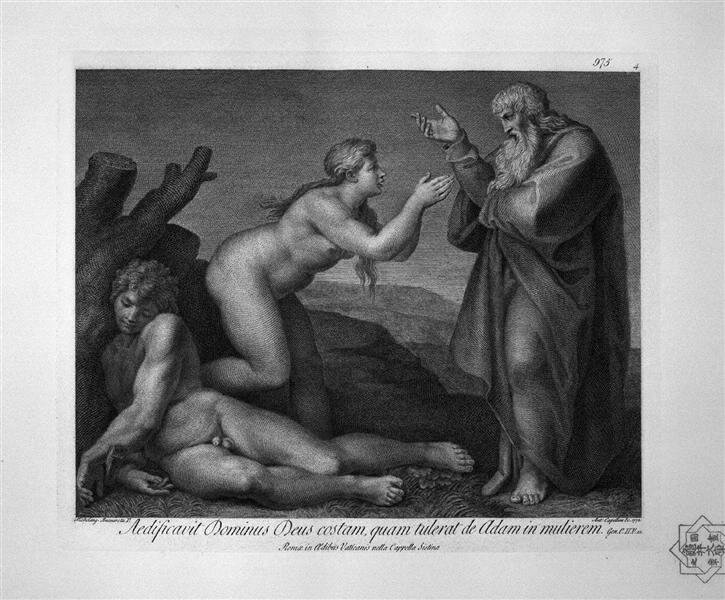

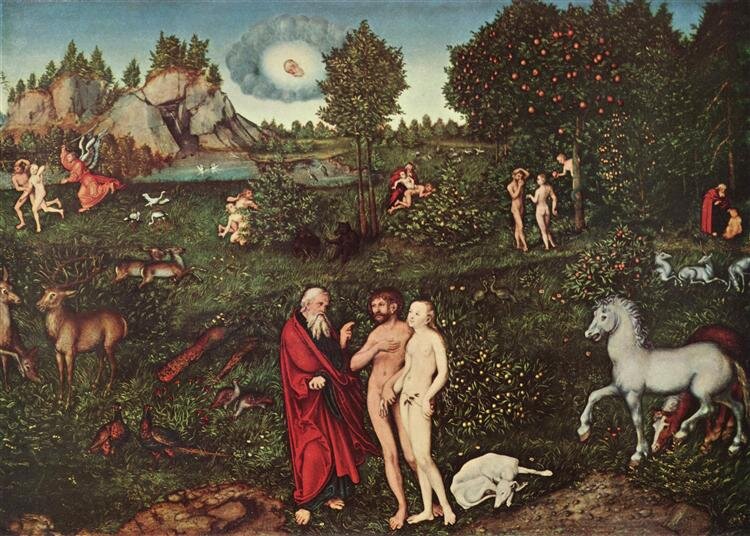

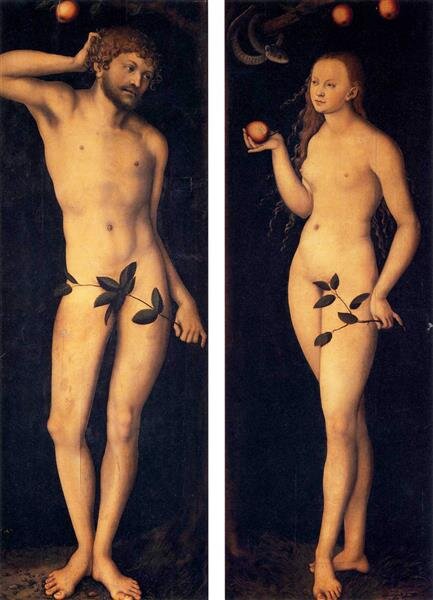

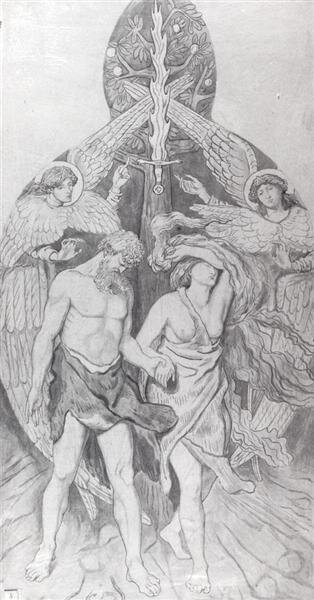

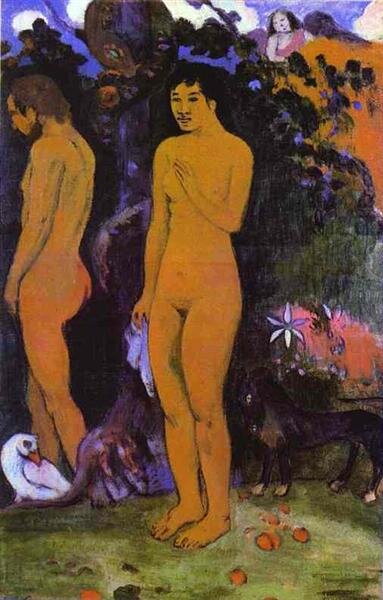

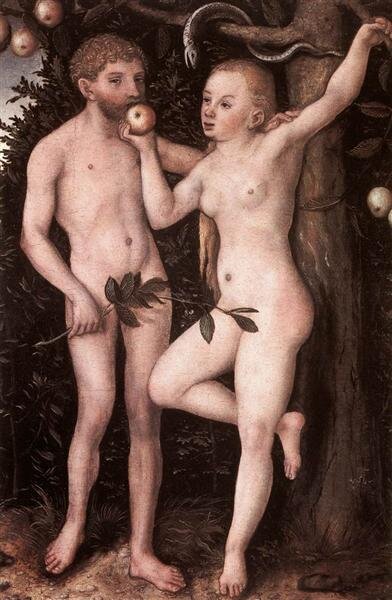

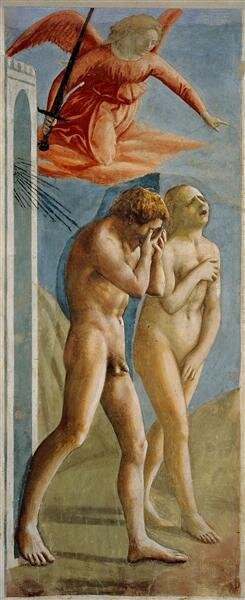

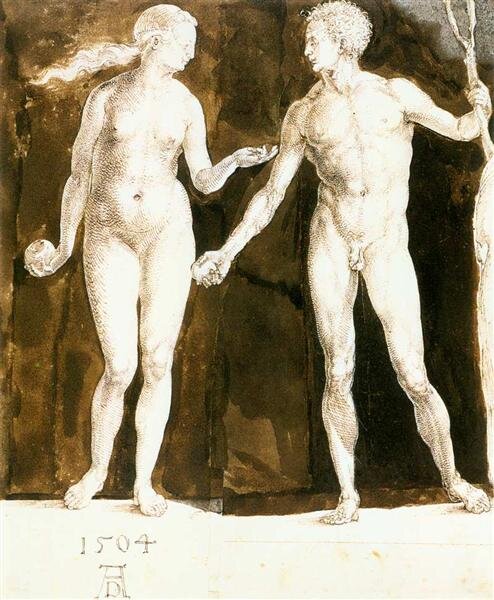

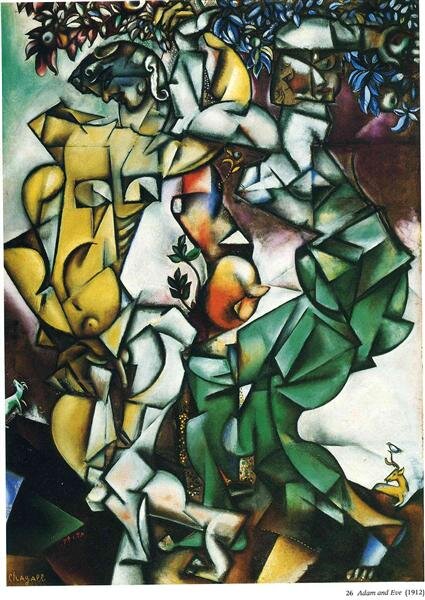

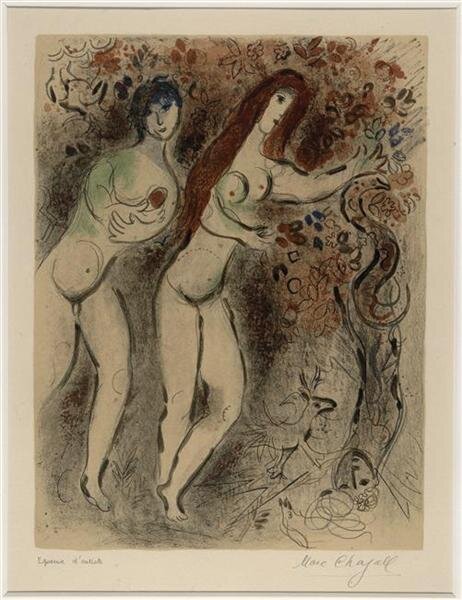

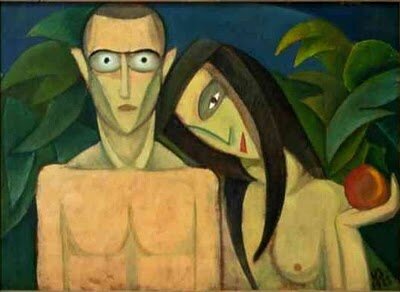

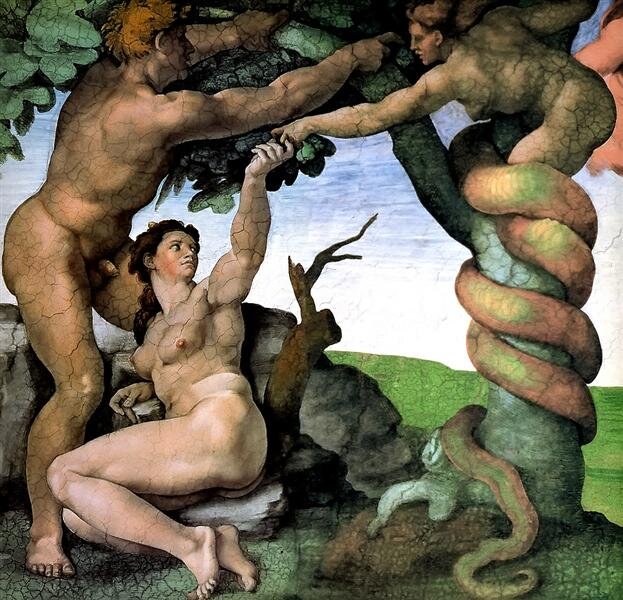

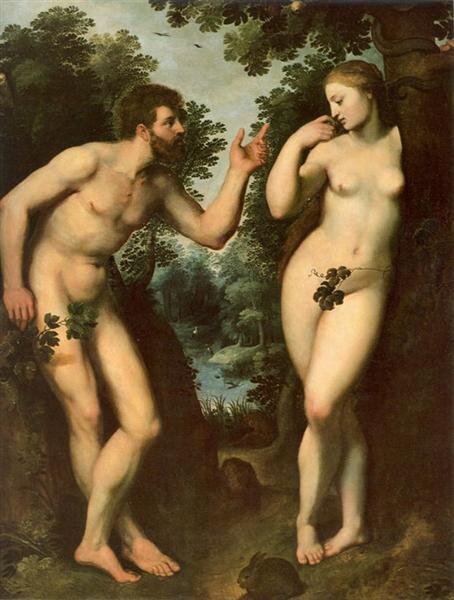

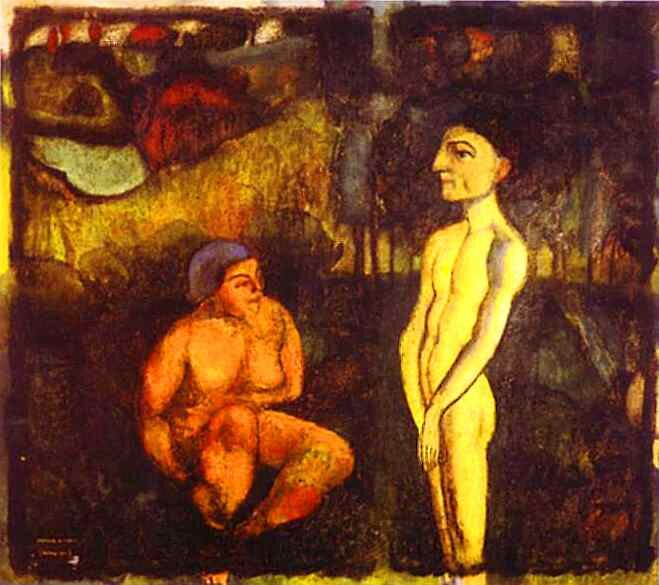

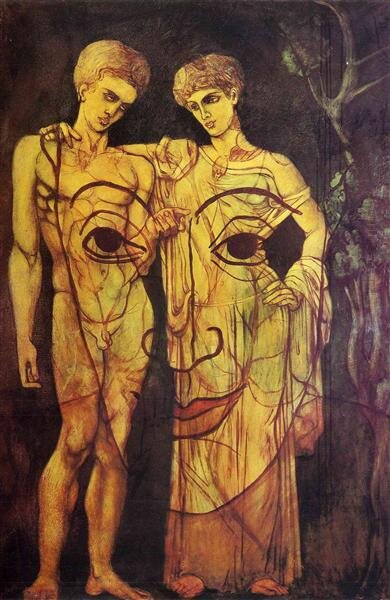

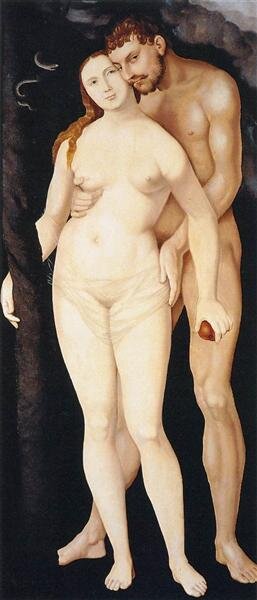

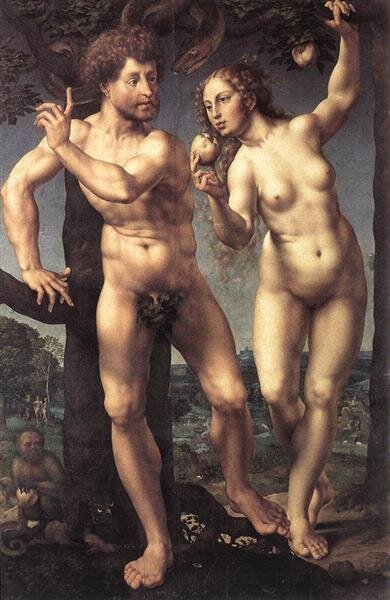

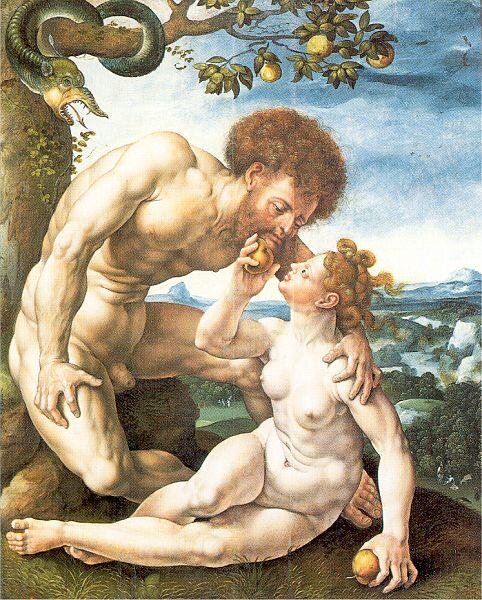

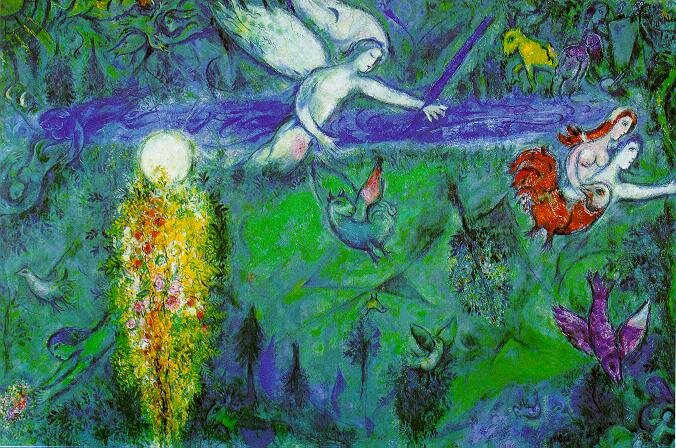

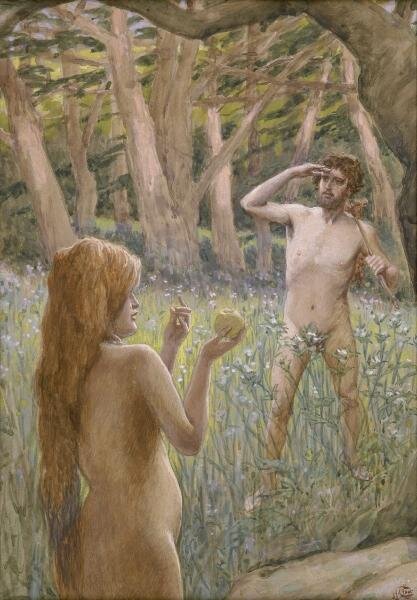

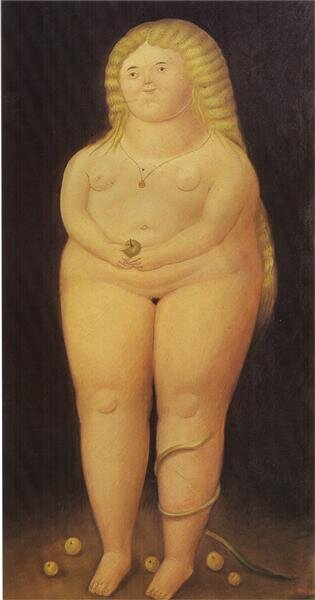

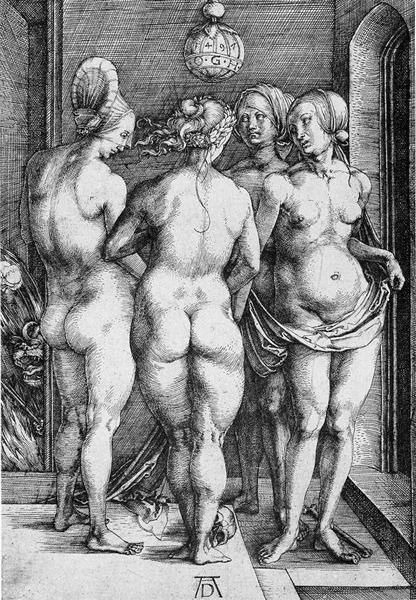

EVE

Eve appears in the Book of Genesis in the Hebrew Bible and also in the Quran. In the Apocrypha, she is said to be Adam’s second wife, after Lilith leaves him. In Genesis 2, Eve is created by God (Yaweh); taken from the rib of Adam to be his companion. The two are given the task of guarding and keeping the Garden of Eden. Adam is instructed that they are forbidden to eat the fruit from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Although Eve is apparently not present when God commands Adam not to eat the fruit, it is understood that she is aware of the command. One day, however, a wily serpent (with legs) speaks to her and entices her to taste the forbidden fruit. Eve succumbs and shares the fruit with Adam. Having eaten the fruit, the pair become aware of their nakedness and hurriedly construct some garments to cover themselves. All of this incurs the wrath of God. The three are then judged and subsequently expelled from the Garden of Eden. Eve (and all resultant womankind) is cursed with a life of sorrow, the pain of childbirth and a subservient relationship to her husband; and the serpent is cursed to crawl on its belly the rest of its days. In some versions of the story the serpent is equated with Satan, and Eve’s sin is equated with sexual temptation.

While in the story of Eve, the snake is a symbol of Evil, in the story of Prudence, the snake seems to regain it’s original sacred power.

Prudence/ Metis

Prudence is an allegorical personification of virtue. Her attributes are a mirror and a snake. Known as one of the Cardinal Virtues (Justice, Temperance, Courage and Prudence) Prudence is often depicted holding the mirror of truth in her left hand, symbolizing the reflection of every thought which must wisely contemplated and assessed; and holding a compass in her right hand, symbolizing the extent of any action; accompanied by a snake, or two. Often she is depicted with two faces: at the front, a young woman looking to the future while at the back of her head is seen an old man implying the wisdom of the past.

Prudence is frequently depicted paired with Justitia, the Roman goddess of Justice.

The word, prudence, derives from the Latin, prudentia, meaning seeing ahead, sagacity, and the ability to govern and discipline oneself by the use of reason. Known in Greek mythology also as Metis, she was the first deity of wisdom and deep thought and, interestingly, magical cunning. Perhaps this is where we find a connection with the symbol of the snake.

Notable for being the first wife and advisor of Zeus, King of the Gods, Metis helped Zeus free his siblings from their father Cronus’ stomach. Metis was both a threat to Zeus and an indispensable aid. When she was swallowed by Zeus after it was foretold that she would bear a son mightier than his father, Metis helped their daughter Athena escape from this forehead, fully grown, wearing the armour Metis had made for her. Athena became the goddess of wisdom, warfare and crafts.

In Greek mythology, Themis is the goddess of justice, divine order, law and good counsel. She was Zeus’ second wife. What either of these women saw in Zeus as a spouse is difficult to imagine.

It is interesting to consider the connections between idealization and vilification.

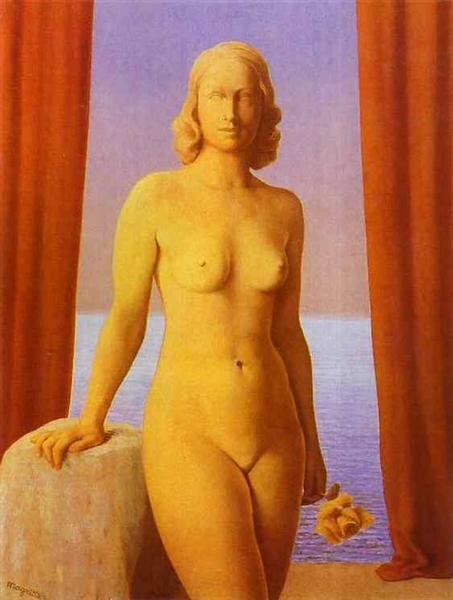

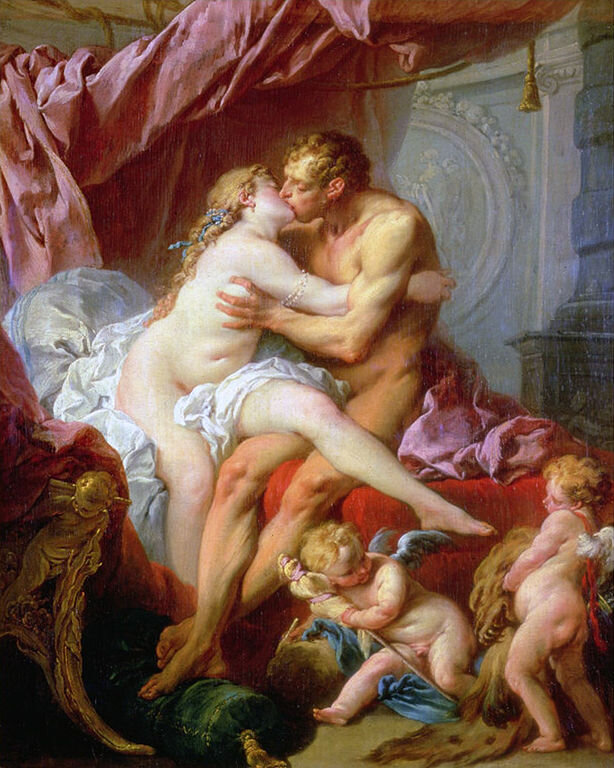

Venus

Venus is the Roman Goddess of Love, beauty, prosperity, fertility, truth seeking, sexuality, and victory. In Greek mythology she was known as Aphrodite. Venus was the mother of Cupid, the god of love. Venus-Aphrodite was born of sea-foam, which represented the watery, fluid, yielding aspect of the female personality. Aphrodite — Venus is idealized as the pinnacle of feminine beauty and charm. She is also vilified for being unfaithful.

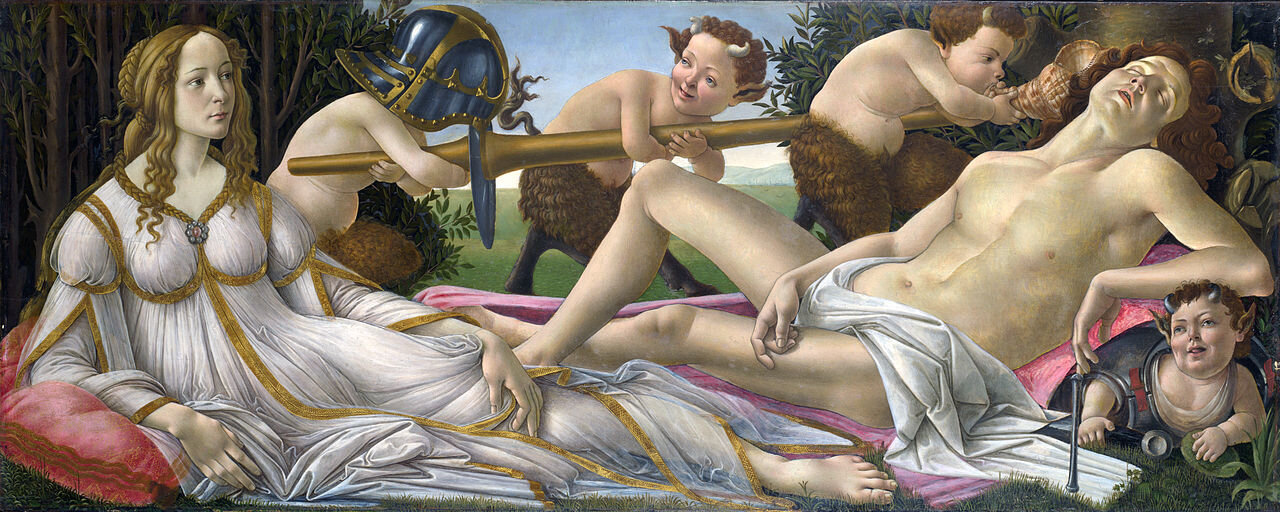

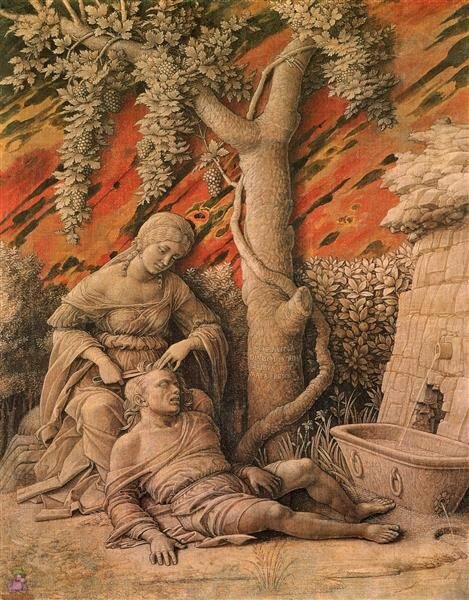

Botticelli’s masterpiece, Venus and Mars, depicts an intriguing moment in the illicit relationship between Venus and Mars.

In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the lovers Venus and Mars are discovered by Venus’ husband, Vulcan, who forges an invisible net of light bronze chain which descends unnoticed upon the cavorting couple, capturing them in the act. Vulcan then calls all the other gods and goddesses to gather to witness and mock the adulterous couple.

Botticelli’s painting does not depict the moment of their discovery. Instead we see a very different scene which seems laden with the symbolism of Christian morality. Venus — fully clothed and very much awake — sits opposite Mars — sprawled naked, fast asleep and evidently snoring in post-coital oblivion. Venus seems to be displeased or disappointed. Her hair seems to become part of the jewelry and costume she is wearing. This may be an oblique reference to the hair shirt worn by penitents. Mischievous Satyrs meanwhile play with Mars’ armour and leer out at the viewer. Satyrs are followers of Bacchus the god of wine, fertility and religious ecstasy. One of them is about to blow a conch shell in Mars’ right ear, which both threatens to awaken Mars and startle the wasps buzzing around his left ear. We know from the story that the couple will get stung in more ways than one. The shape of the painting indicates that likely belongs in the category of paintings called Spalliera: a decorated backboard mounted on a wall, often mounted above a cassone (a wooden chest used for storage), or as a headboard to a bed. It might have been hung in a room called a camera (chamber) a special room used occasionally as a bedroom for a married couple on special occasions or for impressing important guests, The painting might have been given as wedding gift to welcome the wife. It might have been intended to serve as a warning that infidelity will not necessarily bring happiness, that it will be the woman who suffers or comes to regret her ways. (Read more in an interesting article on wikipedia.)

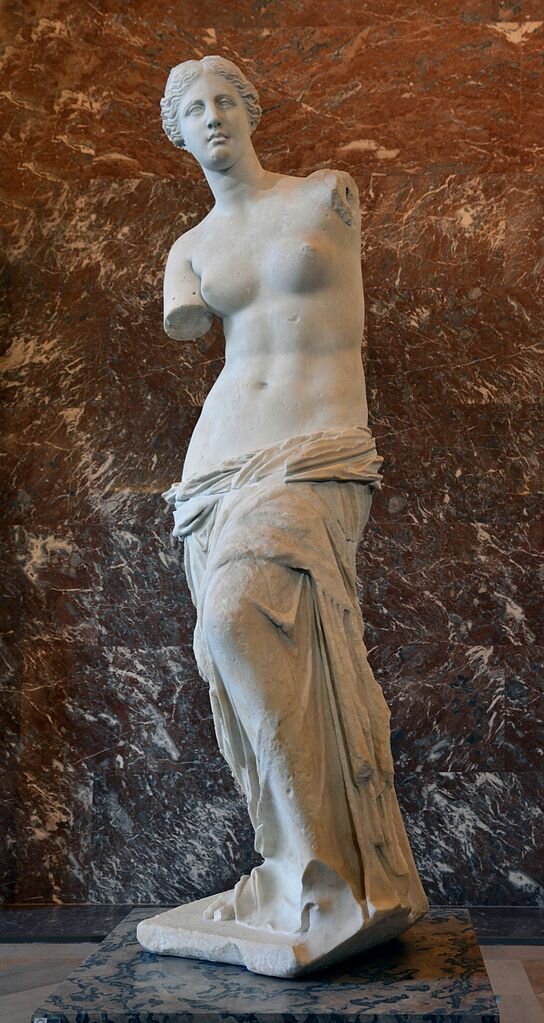

Venus de Milo, Alexandros of Antioch, 130-100 BC, Louvre Museum, image via Wikipedia

It is worth considering the art world’s response to the sculpture of Venus de Milo. Found in pieces, its arms in fragments, the sculpture is considered one of most beautiful images of the idealized female form — due at least in part to its imperfections.

Interestingly, motivational speaker and disability rights activist, Malvika Iyer survived a grenade exploding in her hands, blowing off her arms and severely damaging her legs. Today she works unceasingly to raise awareness about coping with disabilities, modelling accessible fashion and motivating others worldwide. Malvika Iyer asks us to reconsider our ideas of beauty and our definitions of the “ideal woman”.

Helen

Helen was said to be the most beautiful woman in the world. In Homer’s Illiad and Odyssey, Helen is described as the daughter of Zeus and Leda, sister to Clytemnestra, Castor, Pollux, Philonoe, Phoebe and Timandra. (Other sources cite her as the daughter of Zeus and the goddess Nemesis). Helen was married to the Spartan King Menelaus. Her abduction by Paris was the cause of the Trojan War. Although she did not leave Sparta willingly, some have seen her as treacherous because she came to love Paris. When the Trojan horse was admitted to the city, Helen is said to have led a chorus of Trojan women in Bacchic rites, and, holding a torch, signalled to the Greeks from the city’s central tower. Homer describes her as imitating the voices of the Greek women left at home thereby torturing the men inside the horse with the memory of their loved ones. As the war progresses Helen is filled with self-loathing and regret for what she has caused; and by the end of the war the Trojans have come to hate her. In some versions of her story, when eventually Paris is killed in action, she is reunited with Menelaus. In other versions she ascends to Olympus.

Desdemona

Desdemona is a character from Shakespeare's play Othello. She is a Venetian beauty who enrages and disappoints her father, a senator, when she elopes with Othello, a Moorish Venetian military prodigy. When her husband is deployed to Cyprus in the service of the Republic of Venice, Desdemona accompanies him. There, her husband is manipulated by his ensign Iago into believing she is an adulteress, and, in the last act, she is murdered by her estranged spouse.

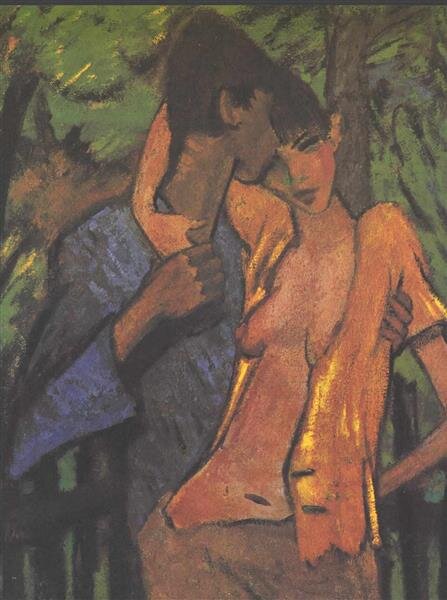

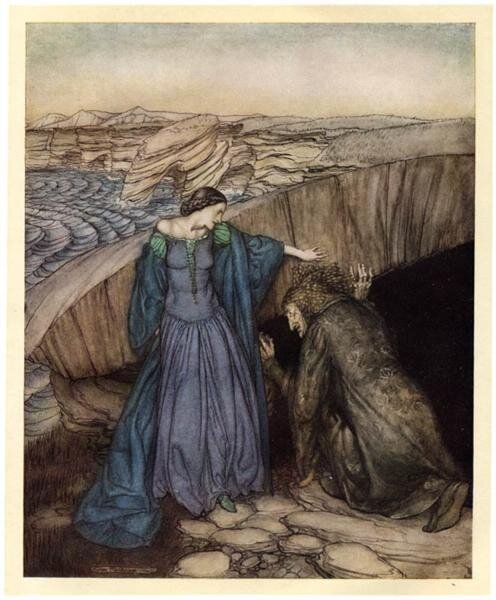

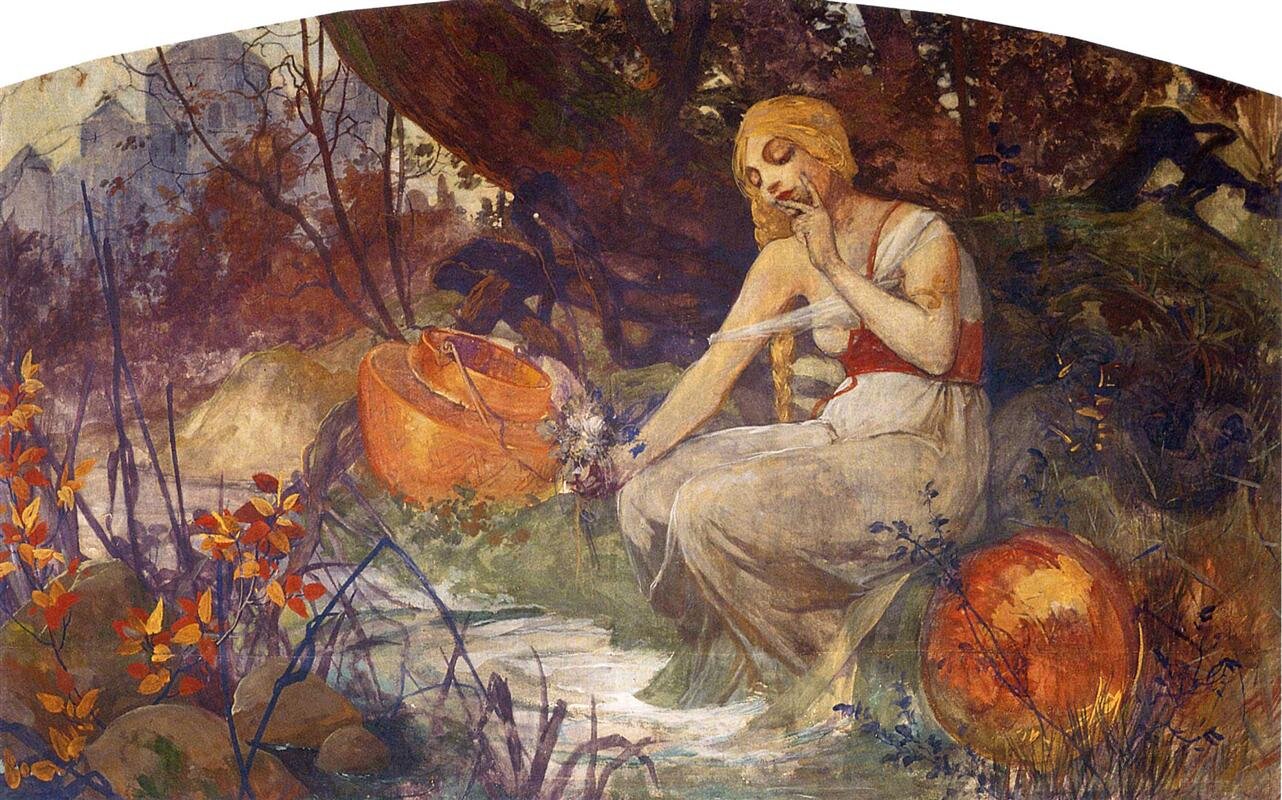

CALYPSO

In Greek mythology, Calypso was a beautiful nymph who lived on the island of Ogygia, where, according to Homer's Odyssey, she detained Odysseus for seven years against his will. Calypso promised Odysseus immortality if he would stay with her, but Odysseus preferred to return home. Eventually, after the intervention of the other gods, Calypso was forced to let Odysseus go.

CIRCE

In Greek mythology, Circe was a beautiful and enchanting goddess, renowned for her vast knowledge of potions and herbs. Through the use of these and a magic wand or staff, she would transform her enemies, or those who offended her, into animals. Homer's Odyssey tells that when Odysseus visits her island of Aeaea on the way back from the Trojan War, Circe transforms most of his crew into swine. Odysseus manages to persuade her to return them to human shape, lives with her for a year and has sons by her, including Latinus and Telegonus.

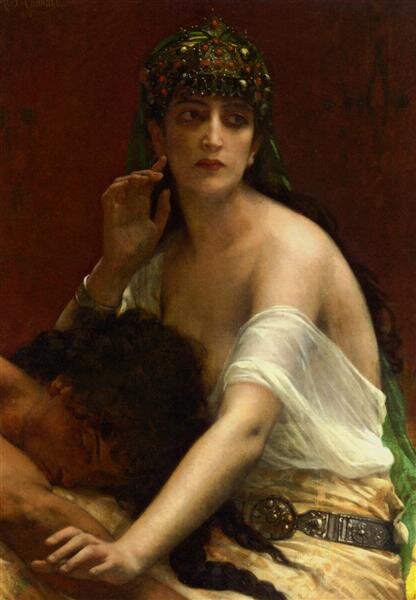

Delilah

Delilah, also spelled Dalila, in the Old Testament, is the central figure of Samson’s last love story (Judges 16). She was a Philistine who, bribed to entrap Samson, coaxed him into revealing that the secret of his strength was his long hair, whereupon she took advantage of his confidence to betray him to his enemies. Her name has since become synonymous with a voluptuous, treacherous woman.

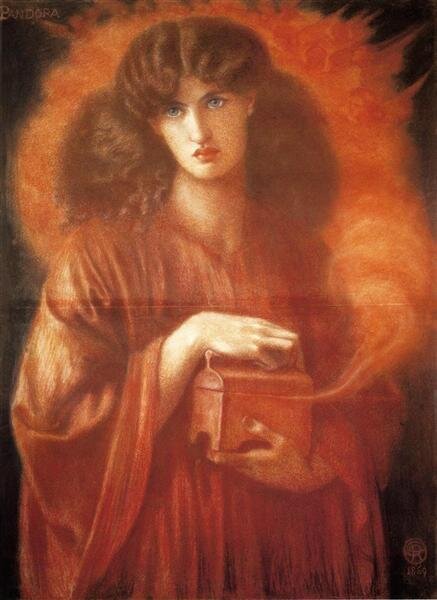

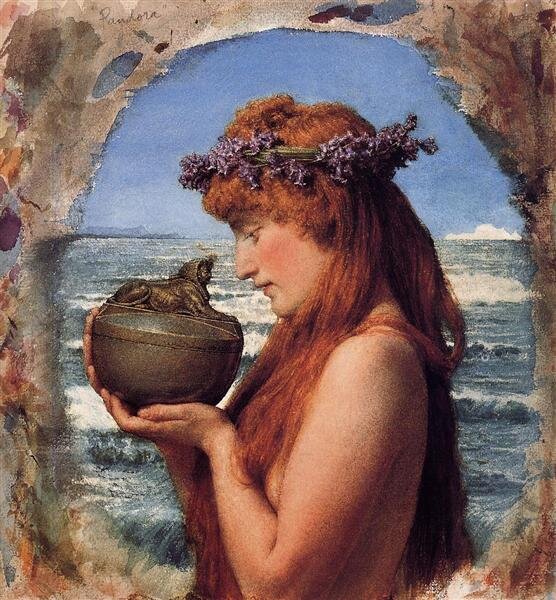

PANDORA

Pandora was the first human woman created by Hephaestus on the instructions of Zeus. Pandora opened a jar, commonly referred to as "Pandora's box", thereby releasing all the evils of humanity.

LILITH

Lilith is a character in Mesopotamian and Jewish mythology, and in the Apocrypha, the hidden writings removed from the Bible. Lilith was Adam’s first wife, created from the same clay as his equal. Lilith, however refused to sleep or serve under Adam. When Adam tried to force her into the “inferior” position it is said that she flew away, copulated with demons and refused to return to Adam.

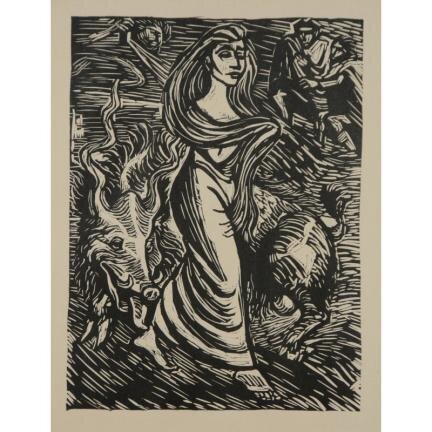

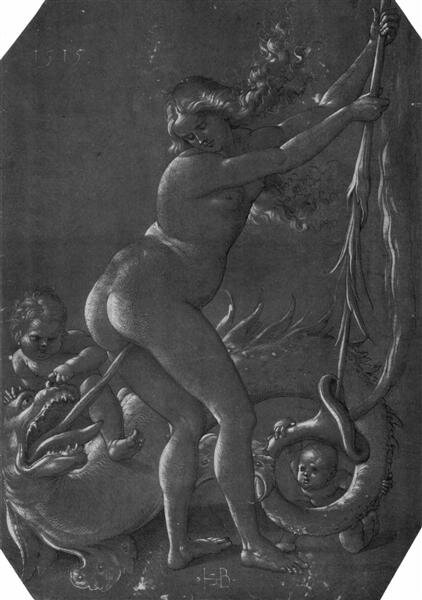

Medea

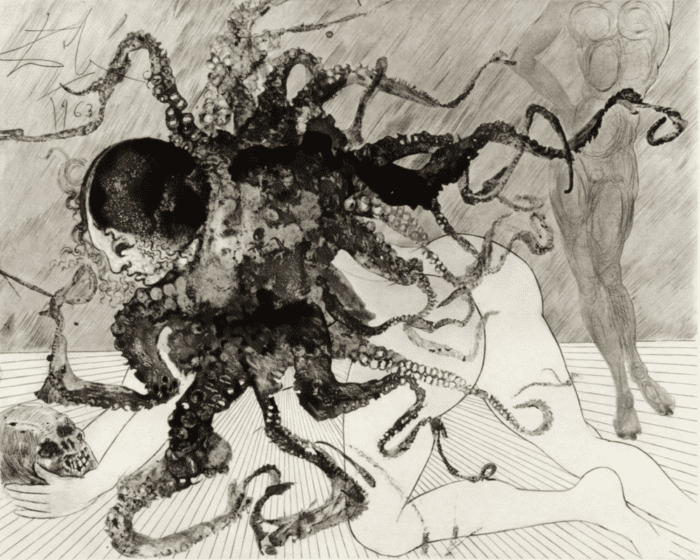

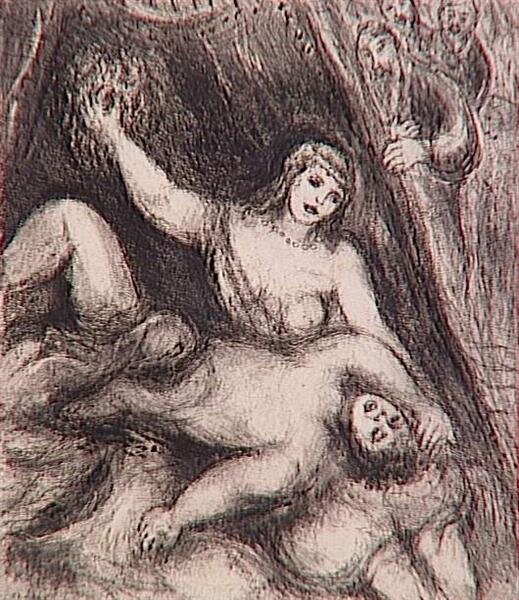

Medea is the daughter of King Aeëtes of Colchis, a niece of Circe and the granddaughter of the sun god Helios. She is primarily known as a sorceress and is often depicted as a priestess of the goddess Hecate. Passionately in love, she aids Jason in his search for the Golden Fleece, assisting him with prescient warnings and magic, saving his life in a series of quests set by her father and playing the role of an archetypal helper-maiden. Jason and Medea then sailed away from Colchis with the fleece, leaving behind the body of her brother Absyrtus who Medea is said to have dismembered and scattered on an island, knowing her father would stop to retrieve them for proper burial.

Medea and Jason then head westwards and eventually settle in Corinth where they have many children. After ten years of marriage, Jason abandons her to marry king Creon's daughter, Creusa, while Medea and two of her sons are banished from Corinth. In revenge, Medea murders Creusa and the king with poisoned gifts (a dress and golden coronet, covered in poison). Medea then continues her revenge, murdering two of her children herself and refusing to allow Jason to hold the bodies. Afterward, she left Corinth and flew to Athens in a golden chariot driven by dragons sent by her grandfather, Helios, god of the sun.

Jael

The story of Jael comes from the Book of Judges, verses 4:11-22 and 5:24-31. Sisera, a defeated Canaanite general flees to a nearby settlement, where Jael takes him in, promises to feed him and hide him from the authorities. The moment he is asleep she drives a tent peg through his temple; an act that earned Jael praise for her courage.

Judith

The story of Judith is from the deuterocanonical books in the Old Testament. Judith is a Jewish widow who uses her beauty and charm to destroy an Assyrian general and save Israel from oppression. Judith and her maid go to the camp of the enemy general, Holofernes. Gradually Judith gains his trust by promising him information on the Israelites. One night, allowed access to his tent, Judith decapitates him as he lies in a drunken stupor. She then takes his head back to her countrymen. The Assyrians, now leaderless, disperse; and Israel is saved. Judith remains unmarried for the rest of her life.

For a modern-day Judith who saved over 3000 Jews from persecution in their homeland, Syria, see Judy Feld-Carr, or click here

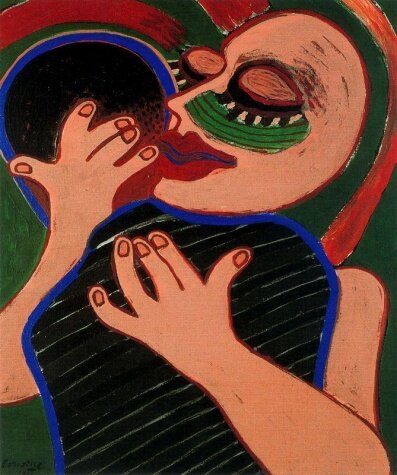

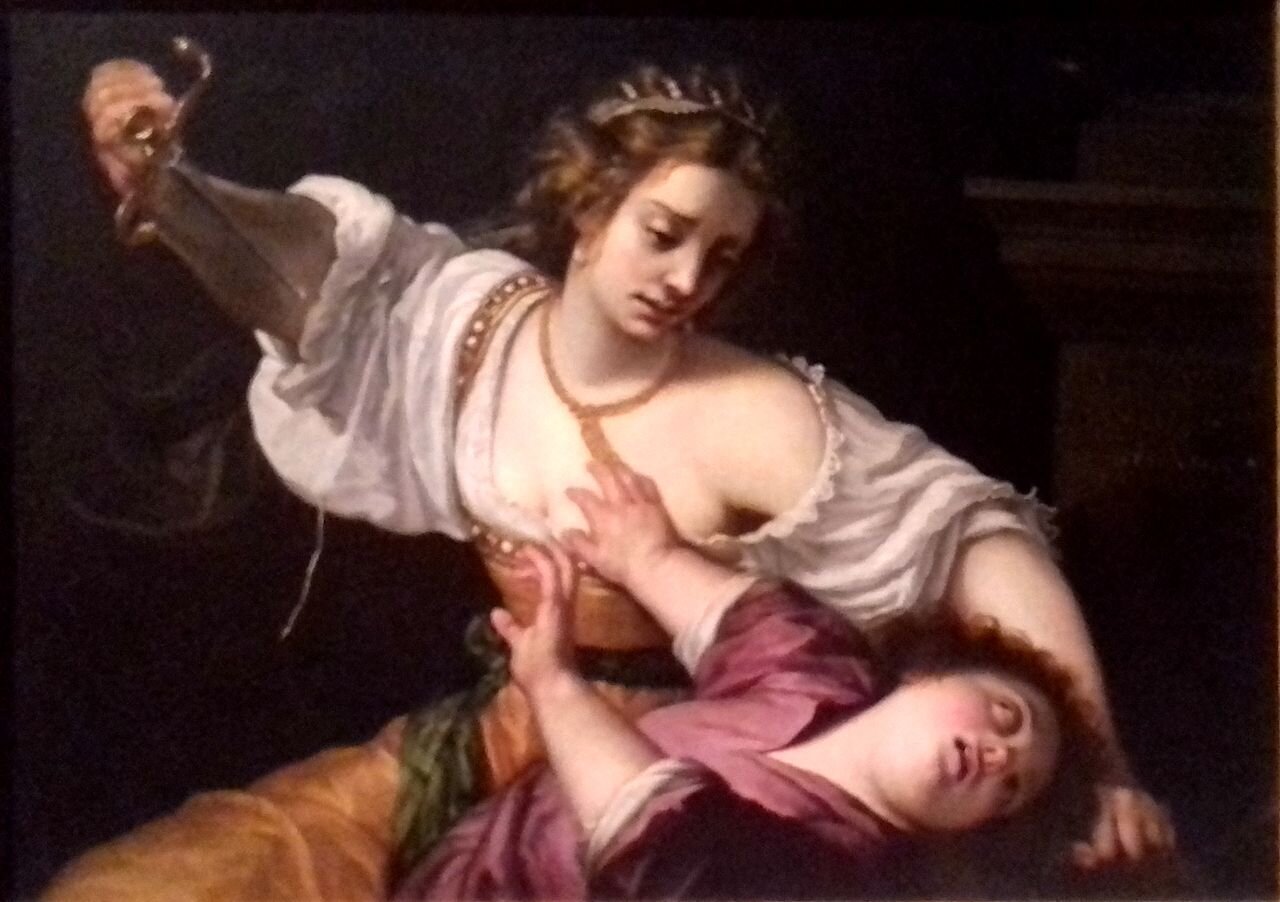

Clytemnestra

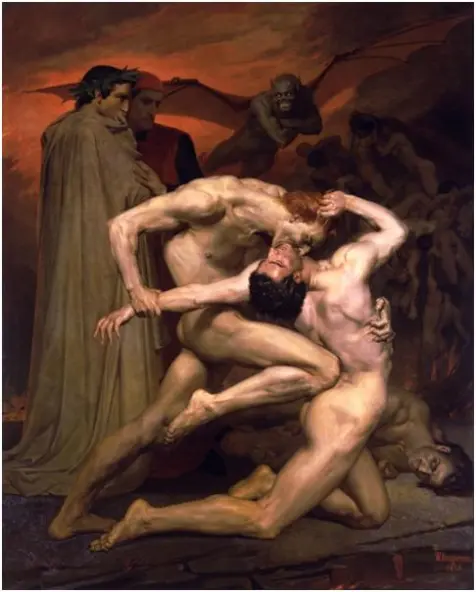

One of the most notorious women in Greek mythology, Clytemnestra was a Spartan princess, daughter of Tyndareus and Leda, wife of Agamemnon, King of Mycenae, and the half-sister of Helen of Troy. During the ten year Trojan War Clytemnestra begins a love affair with her husband’s cousin, Aegisthus. When her husband Agamemnon arrives for a banquet with his concubine, the Trojan princess Cassandra, greeted by his wife Clytemnestra, he tells Cassandra to wait in the chariot. Clytemnestra meanwhile waits until he is in the bath, and then entangles him in a cloth net and stabs him. Trapped in the web, Agamemnon can neither escape nor fight off Clytemnestra — who murders him for sacrificing her daughter Iphigenia to the goddess Artemis. She also murders Cassandra.

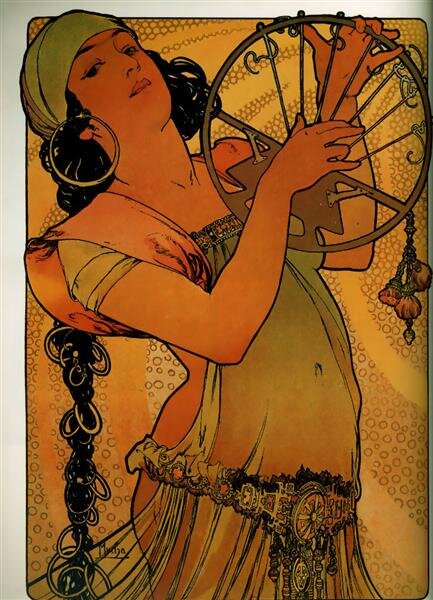

Salammbô

Salammbô is a character in a highly popular, romantic, violent and sensuous historical novel by Gustave Flaubert. A priestess of the city’s moon goddess, and daughter of Hamilcar, chief magistrate and general of Carthage, Salammbô becomes the object of the obsessive lust of Matho, a mercenary leader. The novel tells the story of the siege of Carthage by mercenaries who had not been paid for their help in fighting the Romans.

salome

According to the Gospel of Mark, Herodias bore a grudge against John for stating that Herod's marriage to her was unlawful. Herodias's daughter, Salome danced before Herod at his birthday celebration, was told she could ask for anything in return for her service. After consulting with her mother, Salome is said to have asked for the head of John the Baptist.

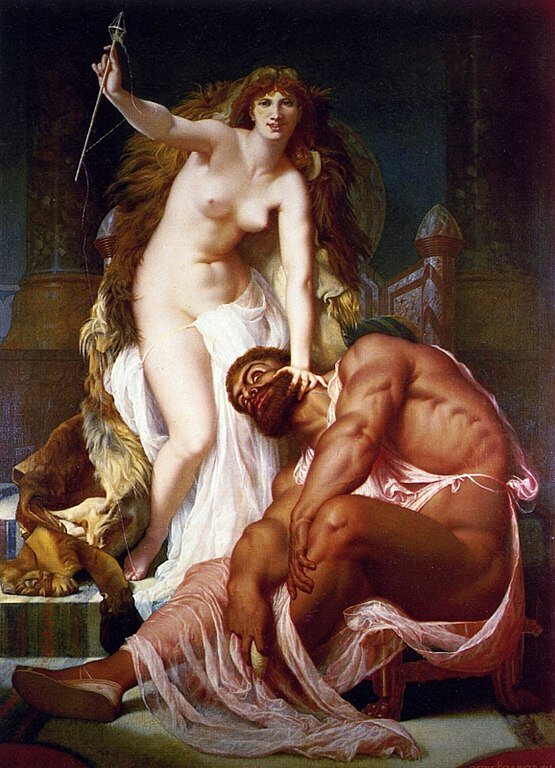

omphale

In Greek mythology, Omphale was the queen of Lydia in Asia Minor, who bought Heracles as a slave, from the god Hermes. Omphale was the daulghter of Lardanus, king of Lydia or a river-god; and became the wife of Tmolus, mountain king of Lydia. After Tmolus was gored by a bull she continued to reign on her own. The Lydians were considered barbarians by the Greeks. It was considered shameful for Heracles to serve a woman in this fashion. Many stories refer to Heracles being forced to do women’s work and wear women’s clothing and helping Omphale and her maidens while spinning.

Deianira

In Greek mythology Deianira is a princess in the court of King Oeneus of Calydon, with whom Heracles falls in love, rapes and promises to come back and marry. While he is away the centaur Eurytion appears and demands her as his wife. Her father complies but Heracles reappears before the marriage, slays the centaur and claims his bride. Deianira has subsequently been associated with combat and described as one who “drove a chariot and practices the art of war”. In some accounts she is known as Hippolyte.

In another version of the story, Deianira and Heracles are on their way to visit a friend. A centaur named Nessus offers to carry Deianira over the river. The centaur, however, promptly runs off with her instead. Heracles shoots him down with one of his venom-tipped arrows. As he lies dying, the centaur realizes his blood is poisoned. He asks Deianira to dip a cloth in his blood, telling her that, mixed with a little olive oil, it will have infallible properties as a love potion. He tells Deianira that if she ever suspects she might be losing her husband’s affections, she must sprinkle some of this potion over his clothing and he will never leave her. When the couple reached their destination Deianira surreptitiously wrings Nessus’s blood from the still-damp cloth into a small phial.

Years pass in which Deianira feels no need for Nessus’ gift. Heracles is busy fighting battles, sacking cities, challenging champions and fathering illegitimate children all across Greece. However, when Heracles captures and falls in love with Princes Iole, Deianira becomes concerned. Previously, Heracles had been sentenced to three years of servitude as punishment for killing Iphitus, the son of King Eurytus. Heracles had killed him because Eurytus had insulted Heracles when he sought unsuccessfully to wed the king’s daughter Iole. With Princess Iole again on the scene Deianira sees a very real rival for her husband’s affections, and this time in her own home.

Deianira takes the supposed love potion and rubs it into one of her husband’s garments: his famous lionskin shirt. The potion begins to act, burning into his skin, and Heracles collapses in agony. Upon discovering that the centaur has deceived her, and that the supposed love potion is in fact poison: Deianira takes her own life. Her name has subsequently been translated as “man-destroyer” or “destroyer of her husband.”

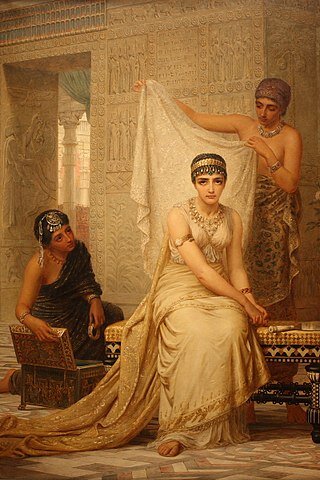

Esther & Vashti

In the Book of Esther (a story found in the Jewish Tanakh (the Hebrew Bible) and in the Christian Old Testament) the Persian king Ahasuerus (also identified as Xerxes I) seeks a new wife after his queen, Vashti, refuses to obey his request for her to leave her own banquet with the women — to dance, wearing nothing but a crown, in front of his male guests. Esther is chosen for her beauty. The King’s reasons: if Vashti refuses to display herself, she must be punished with invisibility and will never be allowed to appear before the king again. She must be replaced with “another who is better than she.”

“The innate fear of women as unworthy partners (and women’s conversations as acts of betrayal) is not new to us as readers. The fear harks back to Eve, the archetypal woman. According to some traditional interpretations, by hosting this banquet in which women reveal secrets to each other, Vashti has committed an act of betrayal and is as guilty as her mother Eve, “the arch betrayer in the eyes of traditionmakers.””

The king's chief advisor, Haman, is offended by Esther's cousin and guardian, Mordecai, and gets permission from the king to have all the Jews in the kingdom killed. Esther foils the plan, wins permission from the king for the Jews to kill their enemies, and they do so. Esther’s story is the traditional basis for Purim, which is celebrated on the date given in the story for when Haman's order was to go into effect, which is the same day that the Jews killed their enemies after the plan was reversed.

“I find in Esther a postcolonial feminist icon – a figure of empowerment who achieves success, not in spite of, but rather because of her identity which becomes a path to achieving liberation for herself and her people.”

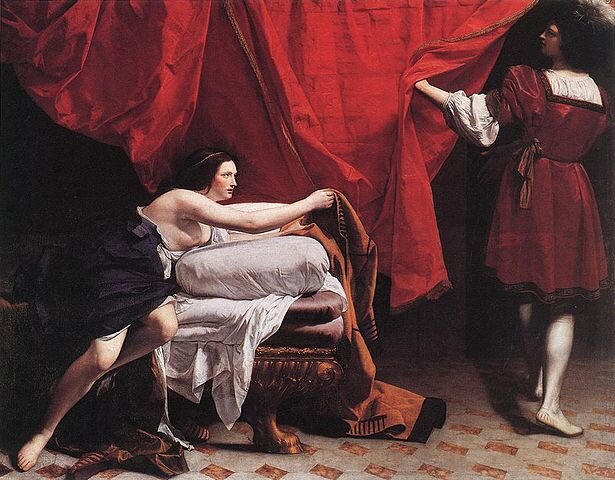

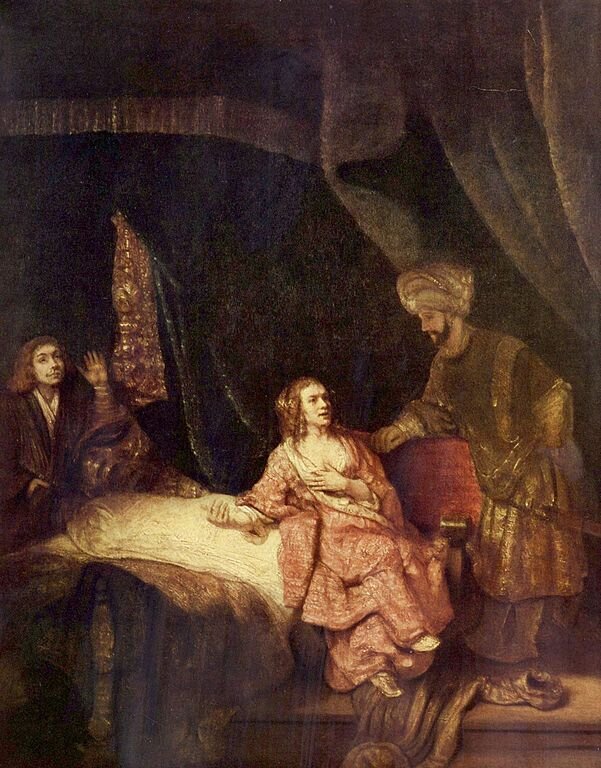

Potiphar’s wife

Potiphar, also known as Aziz in Islam, is a figure in the Hebrew Bible and the Quran. The story begins with Joseph who is sold into slavery by his jealous brothers. Potiphar, the captain of Pharaoh's guard, purchases Joseph as a slave and, impressed by his intelligence, makes him the master of his household. Potiphar's wife, Zulaikha, rather known for her infidelities, takes a liking to Joseph, and attempts to seduce him. Joseph refuses her advances and runs off. Zulaikha retaliates by falsely accusing him of trying to rape her.

Potiphar decides to spare Joseph's life, as rape was punishable by death, but nevertheless has Joseph imprisoned. Because of this there is reason to wonder if possibly Potiphar secretly knew his wife was lying. As for Joseph, his imprisonment causes him to meet a fellow prisoner who introduces him to Pharaoh. Joseph subsequently rises to become vizier, the second most powerful man in Egypt next to Pharaoh.

This story has been told and retold countless times in many Arabic, Persian, Bengali, Turkish and Urdu. In a Sufi interpretation, Zulaikha's longing for Yusuf is said to represent the soul's quest for God.

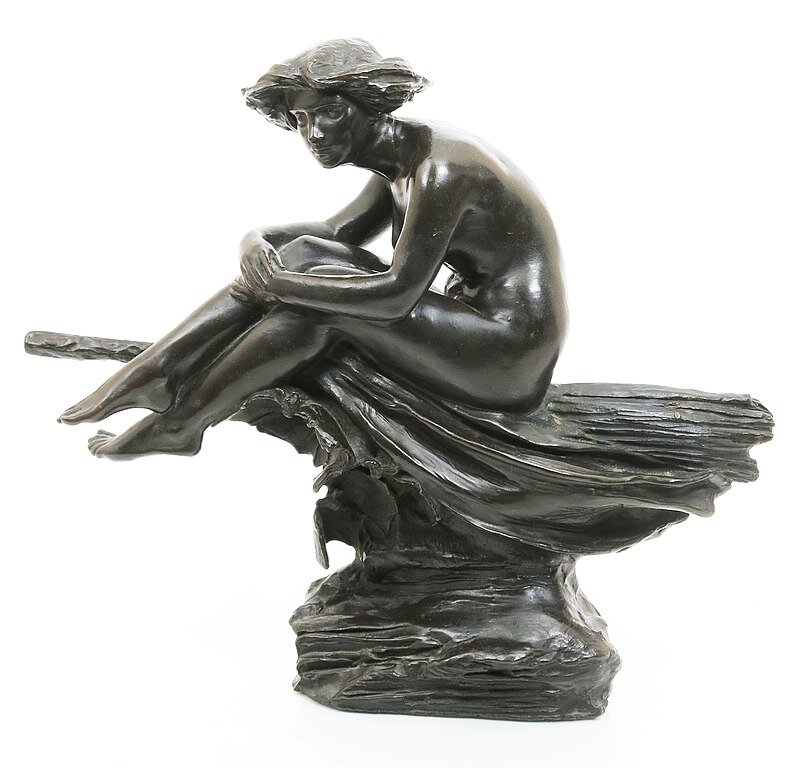

sirens

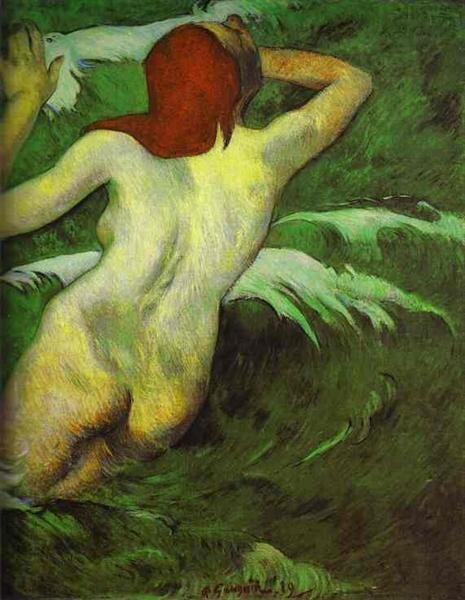

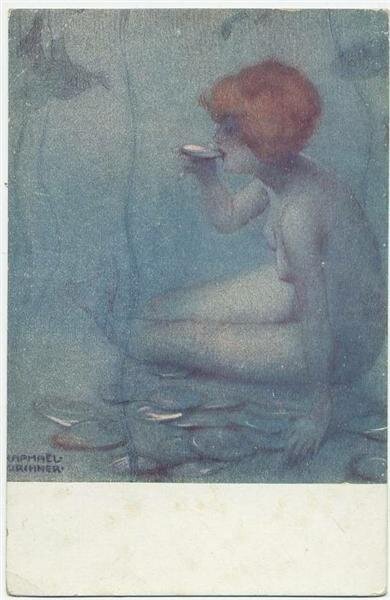

In Greek mythology, Sirens are humanlike beings with alluring voices who lure sailors to their doom. Synonymous with mermaids, sirens were often portrayed with the upper half of the body as human and the lower half as a fish tail. They were also sometimes described as part woman and part bird, either as human-headed birds, or with human upper bodies and bird legs, with or without wings.

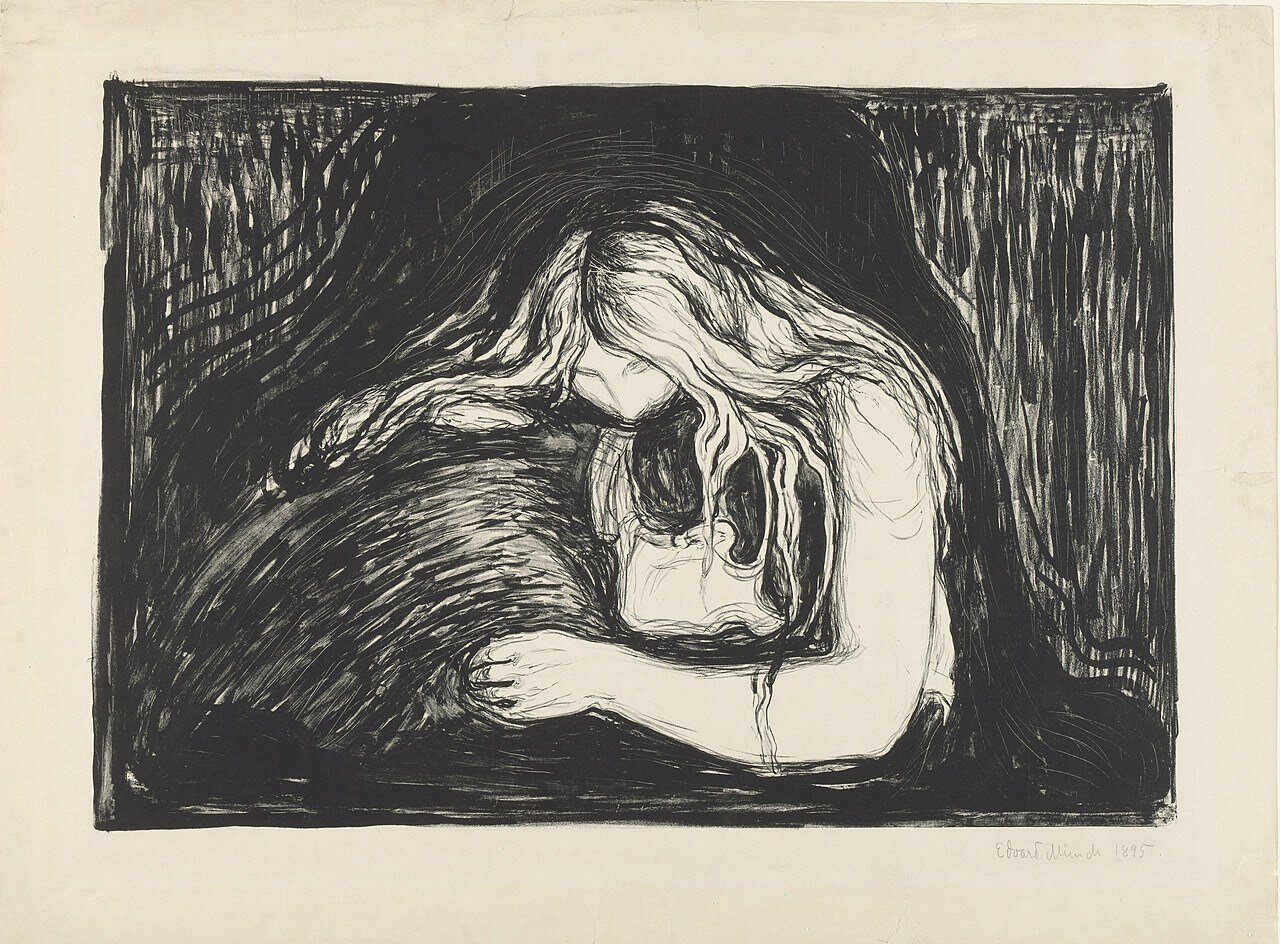

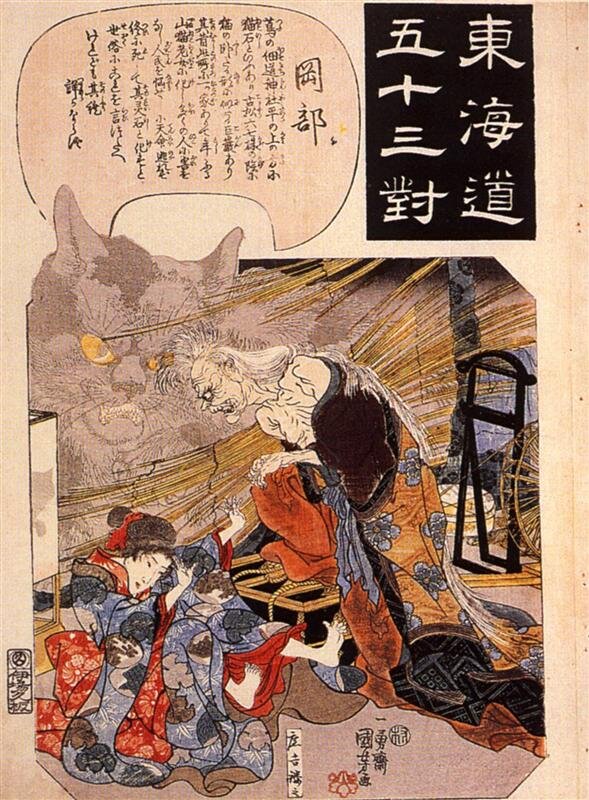

vampires

EVIL TEMPTRESS

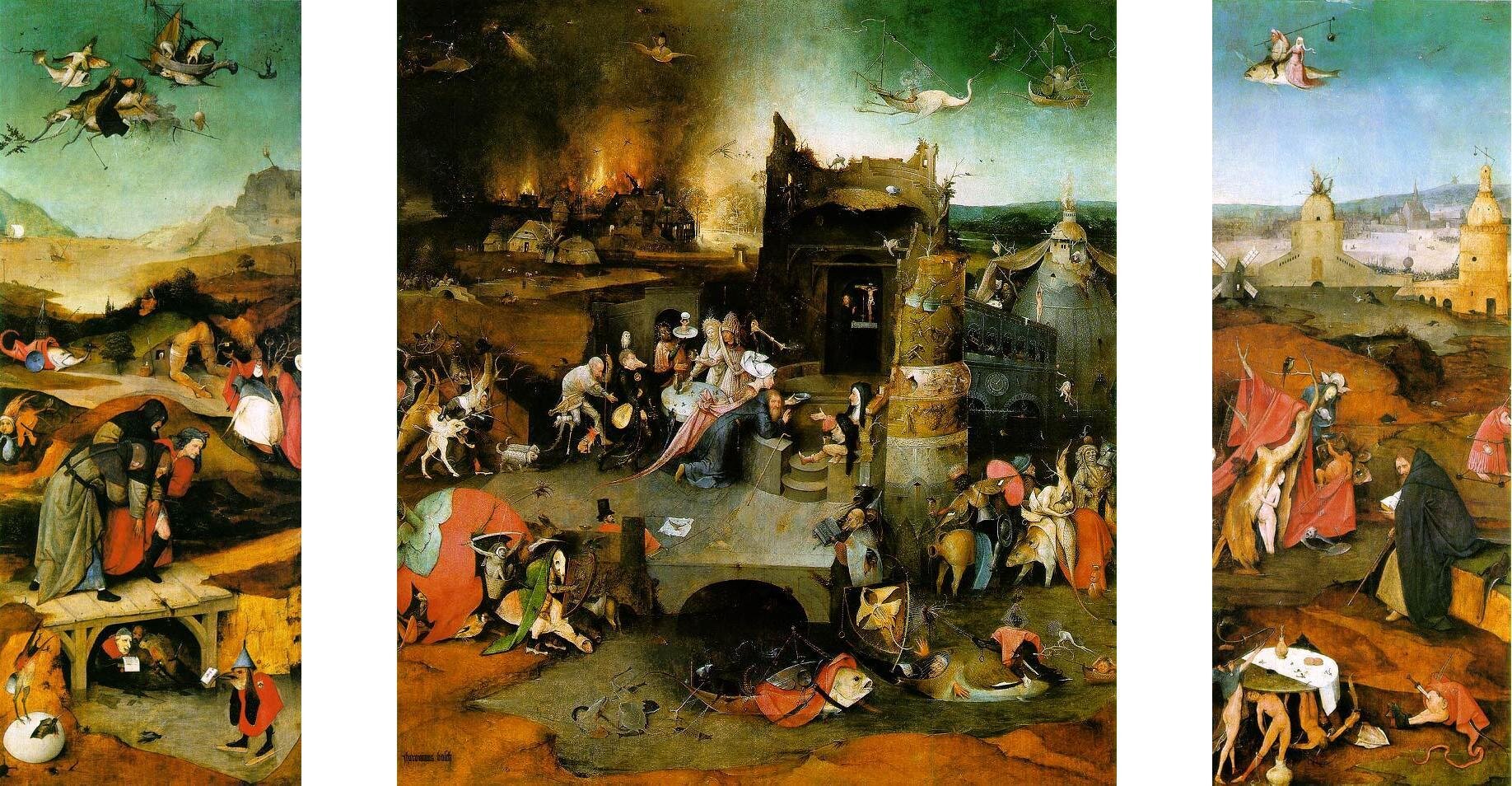

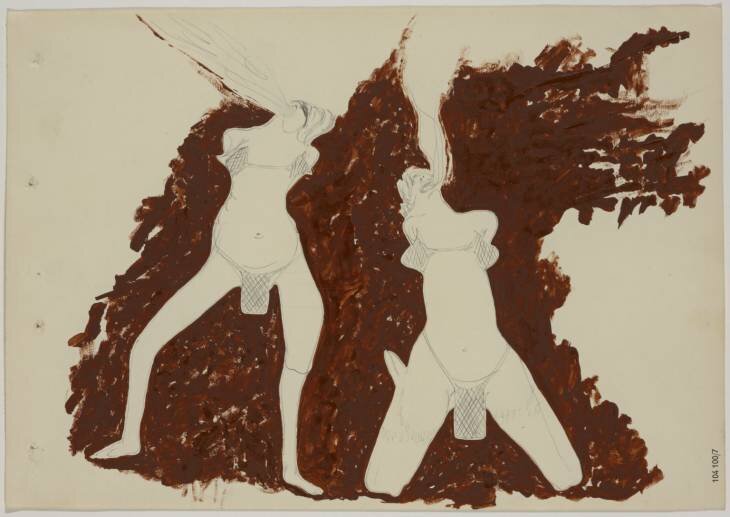

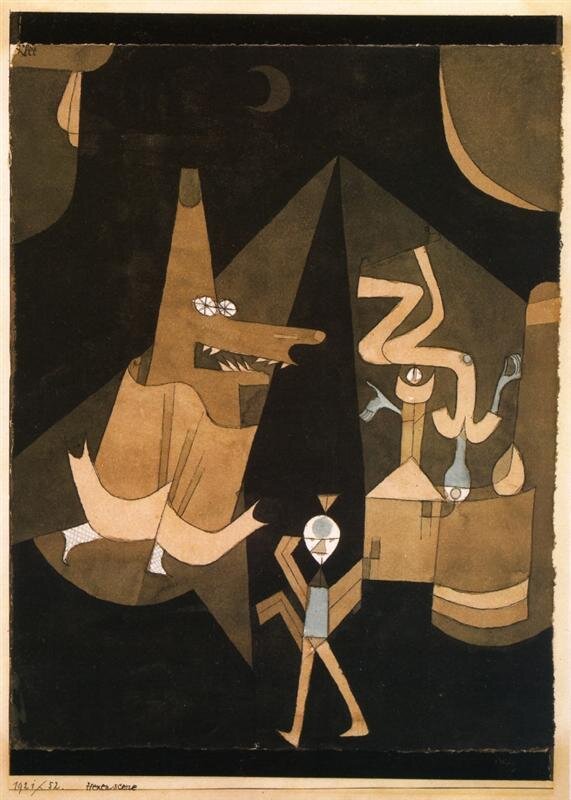

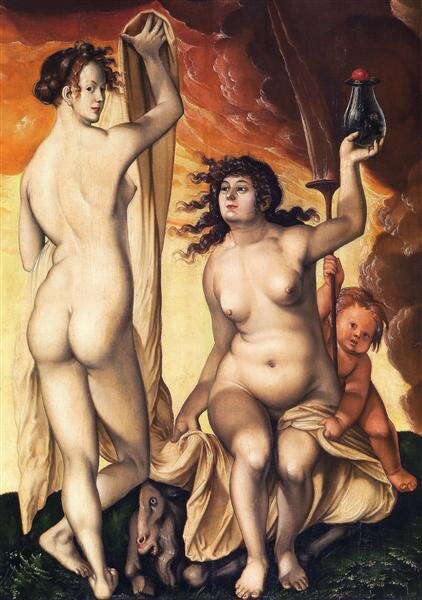

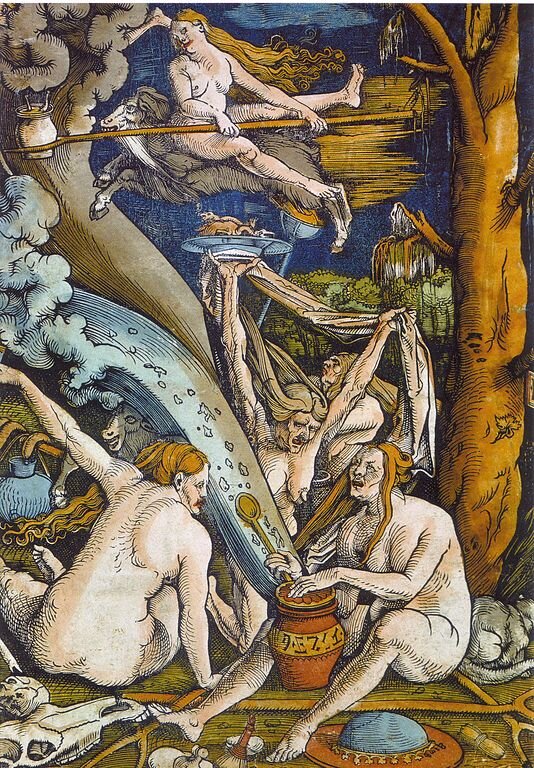

WITCH

Historically, witches were women who were believed to use black magic against others. They were said to commune with the Devil, although such accusations were usually levelled at those deemed to be “enemies of the church”. Often wise women with a knowledge of healing herbs and medicines were mistakenly thought to be witches. Many women were tortured and burned at the stake during the witch-hunts of the Inquisition. For an excellent summary on witchcraft worldwide, read more on Wikipedia.

References

- New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology, Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd., New York, 1959

- Ancient Mirrors of Womanhood, Merlin Stone, Beacon Press, Boston, 1984

- When God Was A Woman, Merlin Stone, Harvest Edition, 1976

- The Civilization of the Goddess, The World of Old Europe, Marija Gimbutas, HarperCollins Publishers, 1991

- The Language of the Goddess, Marija Gimbutas, HarperRow publishers, San Francisco, 1989

- Mythology, The Illustrated Anthology of World Myth & Storytelling, General Editor C. Scott Littleton, Duncan Baird Publishers, London, 2002

- Idols of Perversity: Fantasies of Feminine Evil in Fin-de-Siècle Culture, Bram Dijkstra, Oxford Press, 2003

- Evil Sisters: The Threat of Female Sexuality and the Cult of Manhood, Bram Dijkstra

- Las Hijas de Lilith, Erika Bornay, Ediciones Cátedra, 2020

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Delilah

- https://purehost.bath.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/193106888/Femme_Fatale_2019.03.10.pdf

- https://johnkruseblog.wordpress.com/tag/erika-bornay/

- https://eclecticlight.co/2019/10/25/salammbo-and-symbolism/

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/drsarahbond/2017/11/23/rehabilitating-medusa-powerful-women-sexism-and-reading-mary-beards-new-book/?sh=76a9e1ed4c43

- https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-depictions-medusa-way-society-views-powerful-women

- https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2016/11/the-original-nasty-woman-of-classical-myth/506591/

- https://hyperallergic.com/432102/dangerous-beauty-medusa-in-classical-art-metropolitan-museum/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wadjet

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perseus

- https://www.greekmythology.com/Myths/Creatures/Medusa/medusa.html

- http://employees.oneonta.edu/farberas/arth/arth200/Body/snake_goddess.html

- http://arthistoryresources.net/snakegoddess/votary.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Snake_worship

- https://commons.wikimedia.org

- https://guts4garters.wordpress.com/2009/05/25/the-angry-woman-feminism-medussa/

- https://talesoftimesforgotten.com/2020/10/10/where-does-the-myth-of-medusa-come-from/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caduceus

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gorgon

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Graeae

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Burne-Jones

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Egyptian_hypothesis

- http://arthistoryresources.net/snakegoddess/

- https://rbgstreetscholar.wordpress.com/2007/11/24/black-egyptians-the-original-settlers-of-kemet/

- https://www.mbam.qc.ca/en/collections/arts-of-one-world

- https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-depictions-medusa-way-society-views-powerful-women

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clytemnestra

- https://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/liminar/v19n2/1665-8027-liminar-19-02-57.pdf

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Witchcraft

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siren_(mythology)

- https://www.biblecriticism.com/Esther_Introduction.pdf

- https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/opth-2020-0144/html?lang=en