Nicolas Poussin, 1625-1626, Condé Museum, public domain, image via Wikipedia

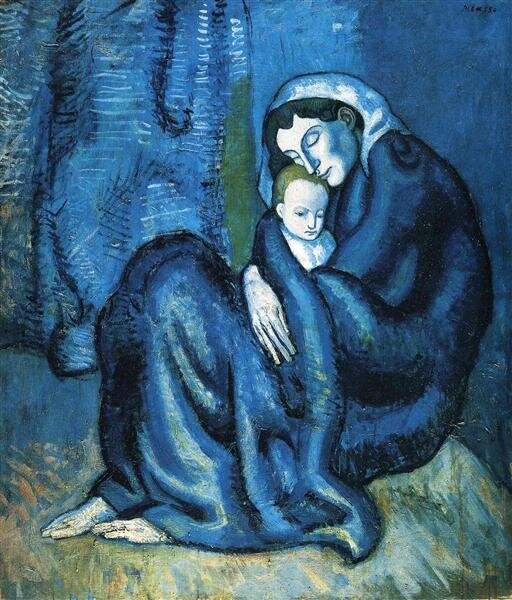

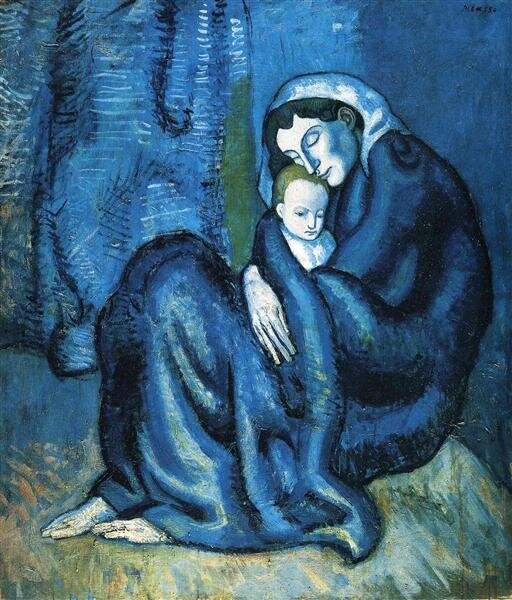

Pablo Picasso, 1902, Expressionism, Fogg Museum (Harvard Art Museums), Cambridge, MA, US

Gregory Crewdson, 1999, Chromogenic print, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Purchased with funds contributed by the Photography Committee, 2000

“In Gregory Crewdson’s photographs, suburban America is besieged by inexplicable, uncanny occurrences. His elaborately staged panoramas often elicit comparisons to the films of Alfred Hitchcock, David Lynch, and Steven Spielberg. Although he eschews the clarity of narrative film, Crewdson engages with his material as a director might, going to great lengths to construct fictional realms, recently employing a crew of up to thirty-five to help realize his cinematic visions.

In Crewdson’s work, meaning is kept just out of reach, where it lurks like a repressed trauma. His early Natural Wonder series (1992–97) focused on wildlife—birds, worms, and insects—forced to the edges of suburbia. These scenes take on the air of mysterious rituals. In one photograph, several birds have created a circular clearing in the grass and lined it with their speckled eggs, over which they stand guard. In another image, dozens of butterflies converge in a frenzied mass, smothering whatever lies beneath them. These ambiguous activities go entirely unnoticed by people, although a human presence is often suggested in the photographs by placid houses in the background. In his series Hover (1996–97), Crewdson turns to the human realm and explores its darker aspects. Abandoning the close-up views of Natural Wonder for higher, more expansive camera angles, these black-and-white photographs offer glimpses into private backyard sanctums in which disturbing acts occur: a man kneels over a woman who has collapsed and is inexplicably bound by festive balloons; elsewhere, a man obsessively mows his lawn in ever-larger concentric circles.

Crewdson’s most recent series, Twilight (1998–2002), returns to those uncanny suburban motifs, staging them in a more elaborate manner. These dark-toned images are illuminated by shafts of light, as if from some outside force making contact with the inhabitants of the pictured world. In Untitled (pregnant woman/pool) (1999), a woman stands in a small inflatable swimming pool as celestial beams of light shine prophetically on her pregnant belly. The characters often seem lost in internal reverie, like the family members at dinner confronted by their naked mother coming in from the garden. They share physical space but are emotionally lost to one another. The Twilight photographs are self-consciously staged, yet the sense of drama and mystery permeating the scenes compels viewers to overlook this artifice. Like all the artist’s work, these images suggest that at the heart of the American dream of property and privacy, emerging where least expected, darkness lurks.”

Vincent van Gogh, c.1881; Netherlands: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Gregory Crewdson, 2001–02, Chromogenic print, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Purchased with funds contributed by the Photography Committee, 2002

In Gregory Crewdson’s photographs, suburban America is besieged by inexplicable, uncanny occurrences. His elaborately staged panoramas often elicit comparisons to the films of Alfred Hitchcock, David Lynch, and Steven Spielberg. Although he eschews the clarity of narrative film, Crewdson engages with his material as a director might, going to great lengths to construct fictional realms, recently employing a crew of up to thirty-five to help realize his cinematic visions.

In Crewdson’s work, meaning is kept just out of reach, where it lurks like a repressed trauma. His early Natural Wonder series (1992–97) focused on wildlife—birds, worms, and insects—forced to the edges of suburbia. These scenes take on the air of mysterious rituals. In one photograph, several birds have created a circular clearing in the grass and lined it with their speckled eggs, over which they stand guard. In another image, dozens of butterflies converge in a frenzied mass, smothering whatever lies beneath them. These ambiguous activities go entirely unnoticed by people, although a human presence is often suggested in the photographs by placid houses in the background. In his series Hover (1996–97), Crewdson turns to the human realm and explores its darker aspects. Abandoning the close-up views of Natural Wonder for higher, more expansive camera angles, these black-and-white photographs offer glimpses into private backyard sanctums in which disturbing acts occur: a man kneels over a woman who has collapsed and is inexplicably bound by festive balloons; elsewhere, a man obsessively mows his lawn in ever-larger concentric circles.

Crewdson’s most recent series, Twilight (1998–2002), returns to those uncanny suburban motifs, staging them in a more elaborate manner. These dark-toned images are illuminated by shafts of light, as if from some outside force making contact with the inhabitants of the pictured world. In Untitled (pregnant woman/pool) (1999), a woman stands in a small inflatable swimming pool as celestial beams of light shine prophetically on her pregnant belly. The characters often seem lost in internal reverie, like the family members at dinner confronted by their naked mother coming in from the garden. They share physical space but are emotionally lost to one another. The Twilight photographs are self-consciously staged, yet the sense of drama and mystery permeating the scenes compels viewers to overlook this artifice. Like all the artist’s work, these images suggest that at the heart of the American dream of property and privacy, emerging where least expected, darkness lurks.

Gillian Wearing, 1996, Black-and-white video projection, with sound, approximately 4 min., 30 sec., Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Purchased with funds contributed by the International Director's Council and Executive Committee Members: Eli Broad, Elaine Terner Cooper, Ronnie Heyman, J. Tomilson Hill, Dakis Joannou, Barbara Lane, Robert Mnuchin, Peter Norton, Thomas Walther, and Ginny Williams, 1997

Gillian Wearing has regularly explored the boundary between the public and the private in her video and photographic work. Influenced by the British documentary filmmaking tradition, Wearing has frequently used real-life individuals as her subjects. For the series that first brought her notice, Signs that say what you want to say and not signs that say what someone else wants you to say (1992–1993), she photographed strangers on the street holding handwritten placards that advertised their thoughts, feelings, and anxieties. In subsequent video works, she documented the intimate confessions of people who masked their identities through various means: in 10-16 (1997), adult actors lip-synch the prerecorded secrets of adolescents; in Trauma (2000), adults wearing plastic masks with generic children’s faces divulge traumatic experiences from their youths.

Wearing has also examined the private sphere of the family. In her video Sacha and Mum (1996), she directed actors and manipulated the editing process to create a film that explores the complex, contradictory nature of a mother-daughter relationship. Sacha and her mother share an intimate moment as they smile and hug in a bedroom, yet their embrace slowly shifts into a tussle. As love and aggression blur, the mother begins to tug, pull, and otherwise physically dominate her daughter. Sacha’s odd vulnerability and her mother’s aggressive volatility are underscored by the speeded up video, which quickens their gestures, and the distorted sound track that transforms their speech into anxious gibberish. By the film’s end, it is unclear whether Sacha is a disturbed person whose mother is trying to calm her, or if the mother is a disturbed aggressor from whom Sacha is trying to free herself.”

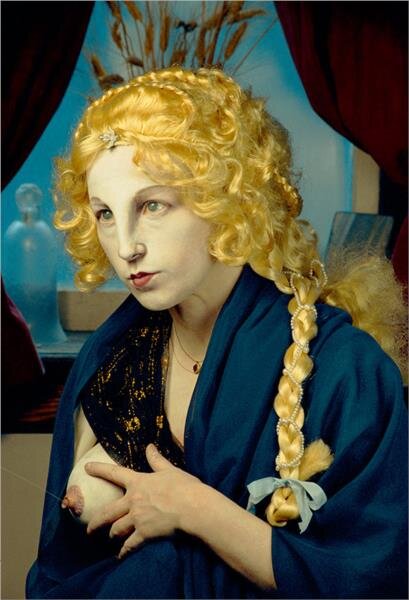

Catherine Opie, 2004, Chromogenic print, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Purchased with funds contributed by the International Director's Council and Executive Committee Members: Ruth Baum, Edythe Broad, Elaine Terner Cooper, Dimitris Daskalopoulos, Harry David, Gail May Engelberg, Shirley Fiterman, Nicki Harris, Dakis Joannou, Rachel Lehmann, Linda Macklowe, Peter Norton, Tonino Perna, Elizabeth Richebourg Rea, Mortimer D.A. Sackler, Simonetta Seragnoli, David Teiger, Ginny Williams, and Elliot K. Wolk, and Sustaining Members: Tiqui Atencio, Linda Fischbach, Beatrice Habermann, and Cargill and Donna MacMillan, 2005

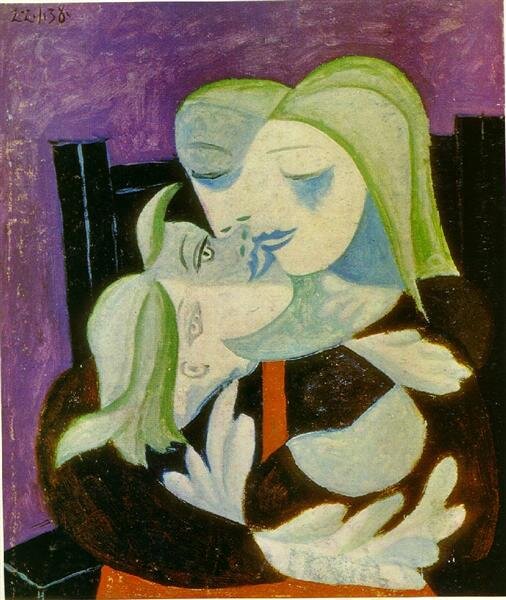

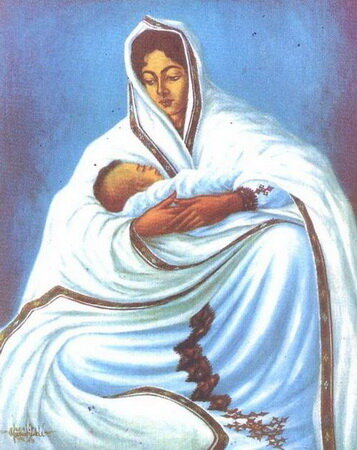

Since the early 1990s Catherine Opie has produced a rich, complex photographic oeuvre that explores notions of communal, sexual, and cultural identity. From her early portraits of queer subcultures, pristine urban panoramas, and expansive landscapes to incisive views of her own domestic life, Opie has offered profound insights into the conditions in which communities form and the terms in which they are defined. Throughout her career, self-portraiture has served as a marker of personal and artistic development, as well as a reminder that she, as the photographer, does not stand apart from the groups she documents. In this vein, she made Self-Portrait/Cutting (1993) and Self-Portrait/Pervert (1994) alongside her renowned series portraying fellow members of San Francisco’s queer leather subculture. Like those images, her self-portraits address contemporary concerns of queer identity, while couching their content in a formal tradition recalling the sixteenth-century paintings of Hans Holbein. In these images Opie offers something deeply personal, even confessional, revealing powerful longings that are compounded by the great physical vulnerability of the sadomasochistic acts the photographs document. Ten years later, in Self-Portrait/Nursing (2004), Opie returned to the genre, newly suffusing her image with a sense of rapturous contentment, as she holds her infant son in a classically maternal pose that further evokes art-historical imagery. Faintly but clearly visible on her chest, the word “pervert” still appears as a scar, a trace of her history that carries forward through time." — Guggenheim

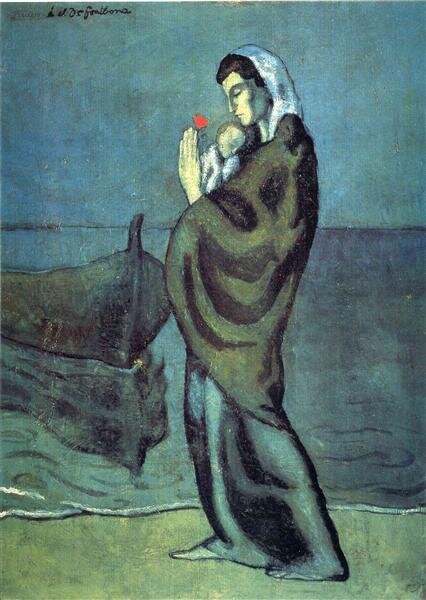

Pablo Picasso, 1903, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Thannhauser Collection, Gift, Justin K. Thannhauser, 1978

Mary Cassatt

1880

Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) Los Angeles, CA, US

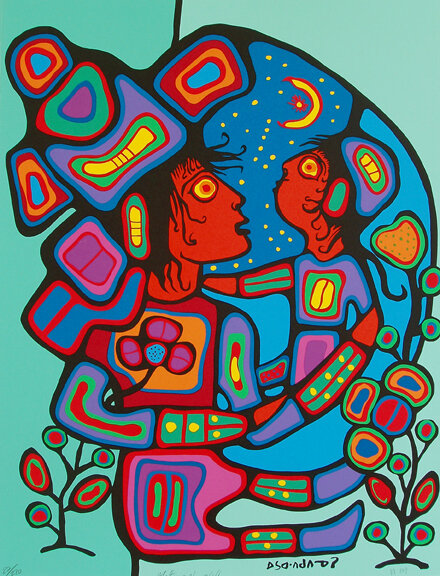

Paul Kane, 1852, Romanticism: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA), Montreal, Canada