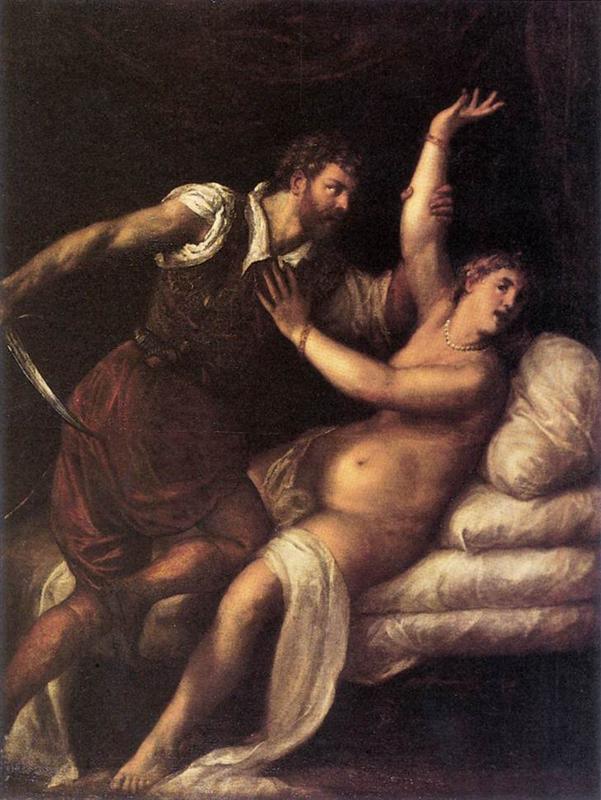

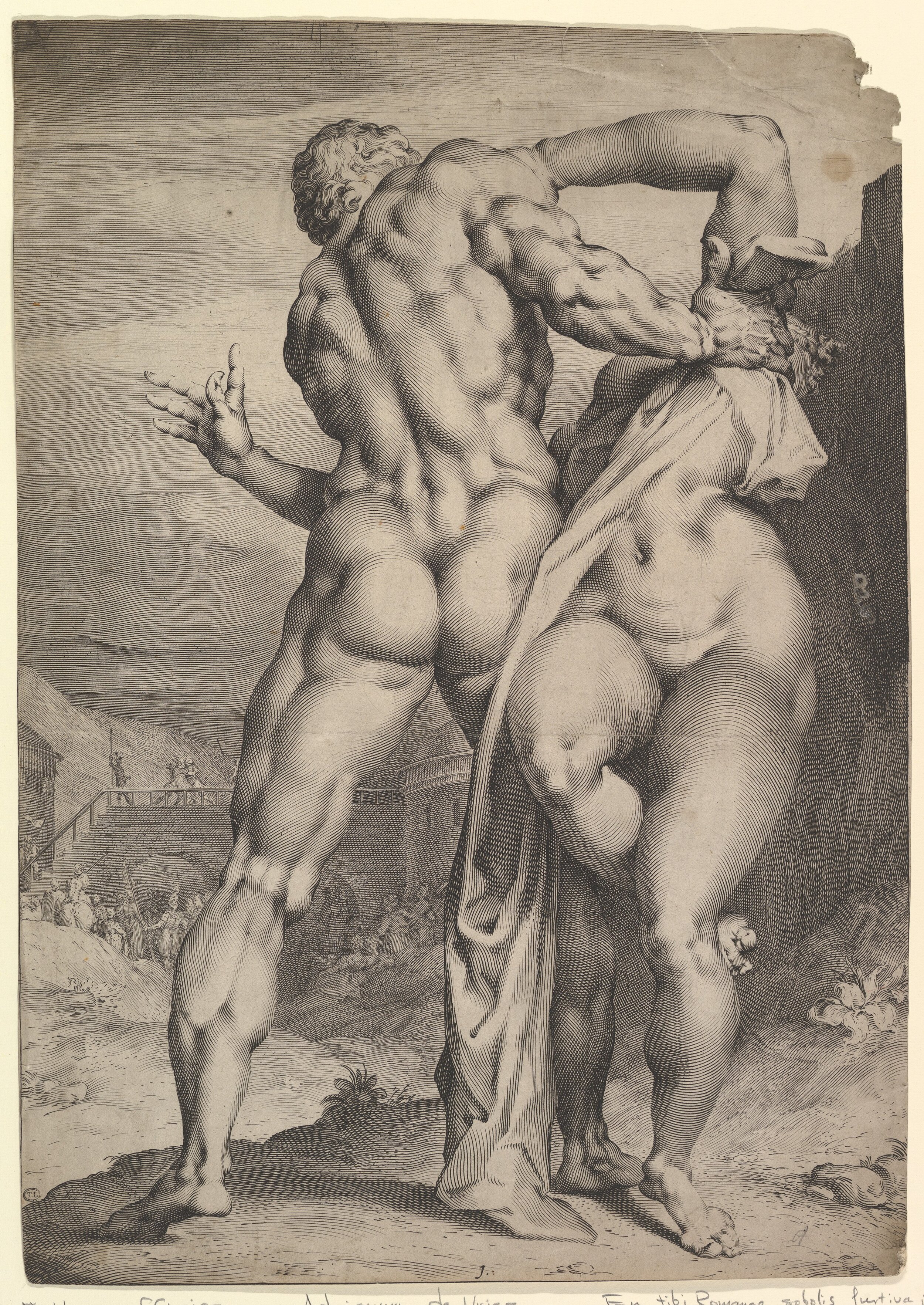

Jacopo Tintoretto (c 1518-1594), Tarquin and Lucretia (E&I 219) (1578-80), oil on canvas, 157 x 146 cm, Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL. Wikimedia Commons.

Eugene Delacroix, 1852, Orientalism

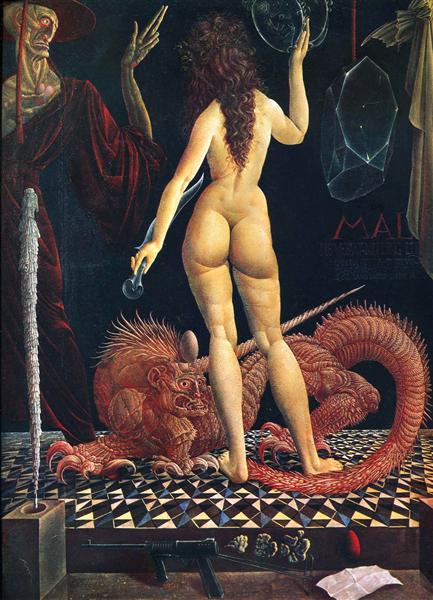

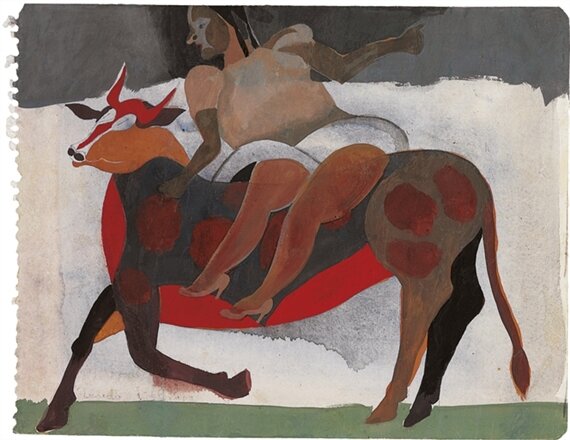

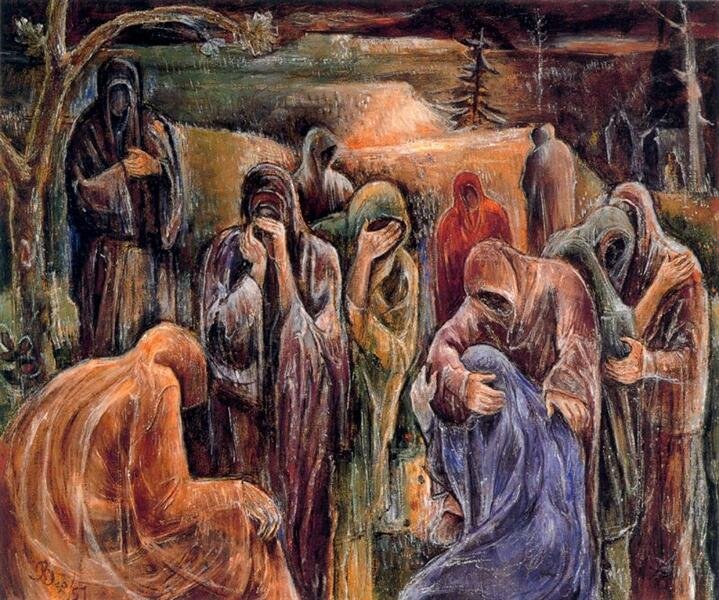

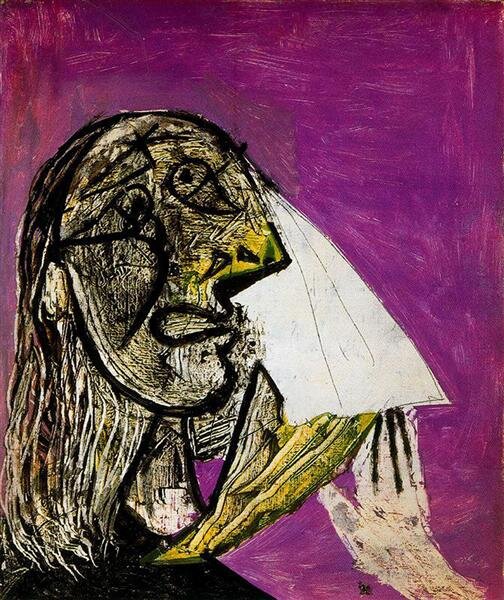

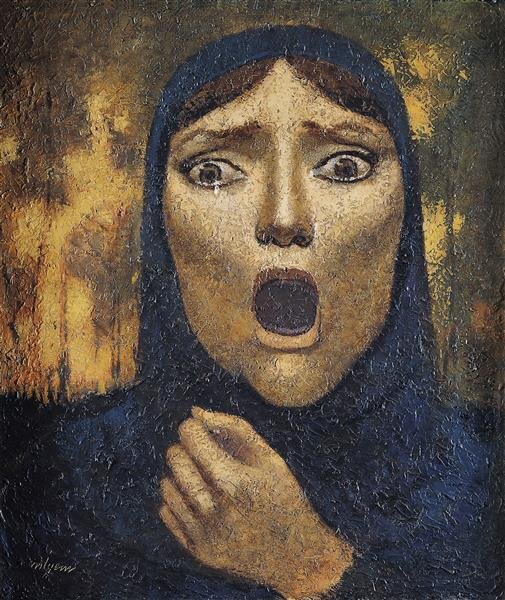

Vilmantas Marcinkevičius, 1994, Modern Art Centre, Vilnius, Lithuania

photo credit: Google

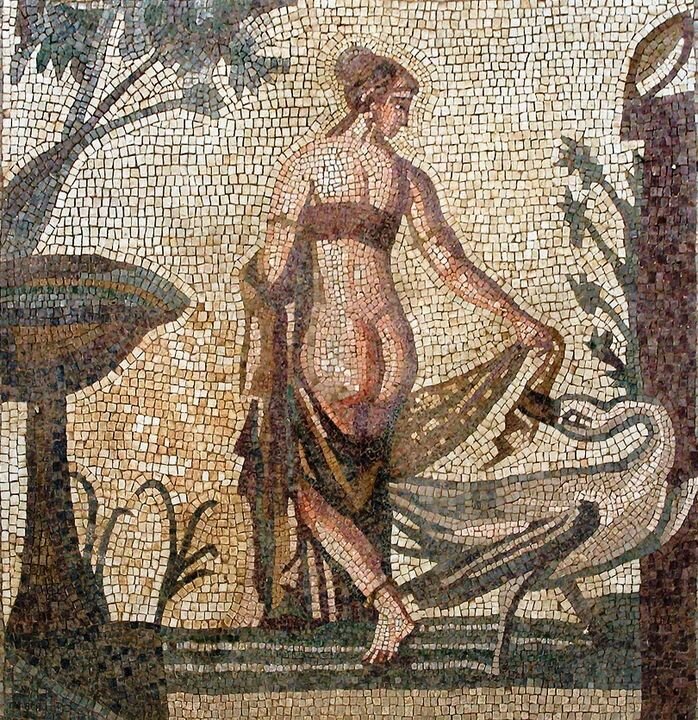

Roman mural from the Casa del Menandro, Pompeii

public domain, image from Wikipedia

Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein, 1806, oil on canvas, Großherzogliches Schloss Eutin

image from Wikipedia

Tondo of an Attic red-figure cup, ca. 440-430 BC, Louvre Museum, Paris

public domain, image from Wikipedia

Cassandra in front of the burning city of Troy, Evelyn De Morgan, 1896

image from Wikipedia

Leonardo da Vinci

1506, Milan, Italy

High Renaissance

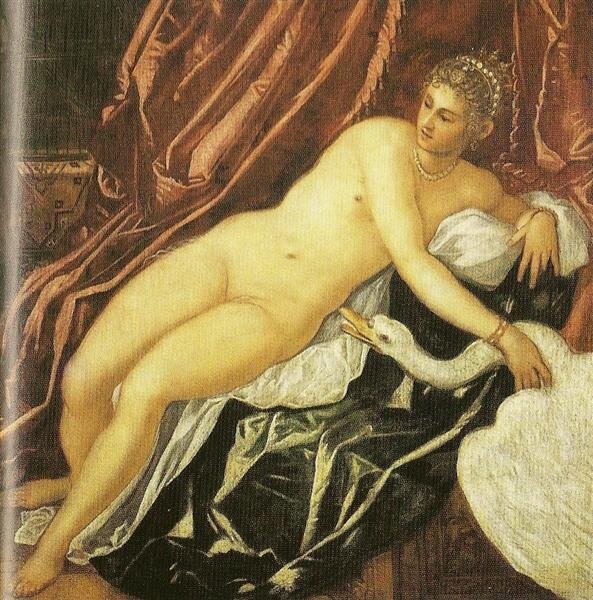

Chatsworth House, Derbyshire, UK

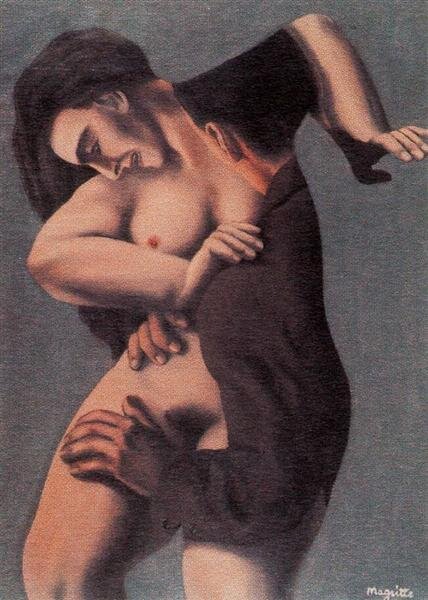

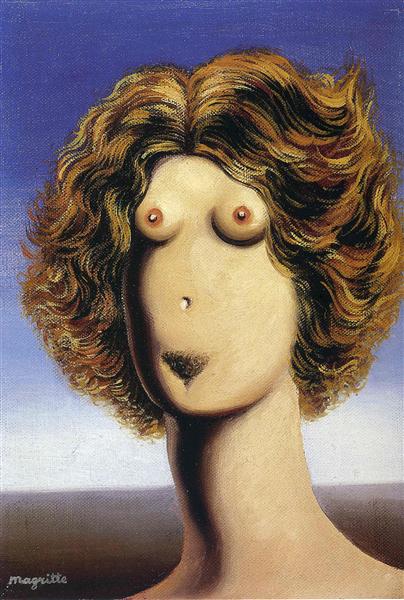

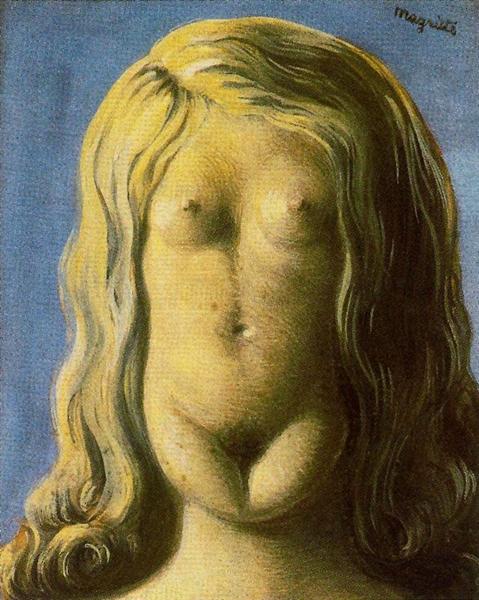

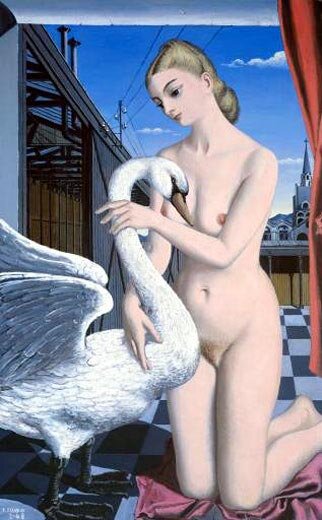

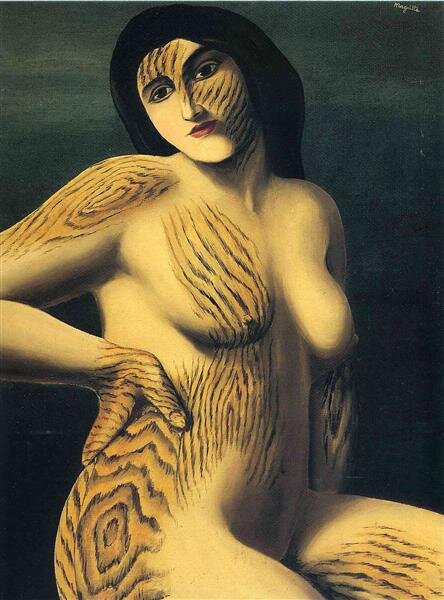

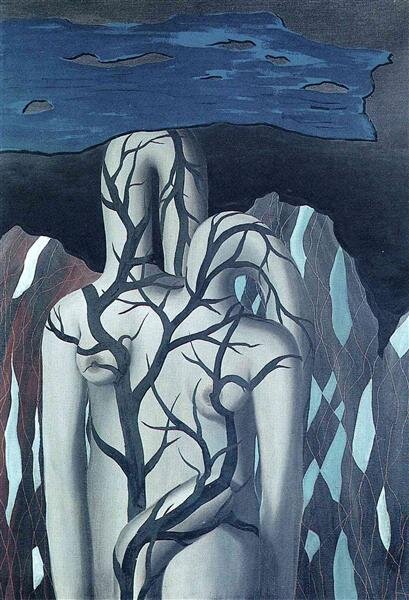

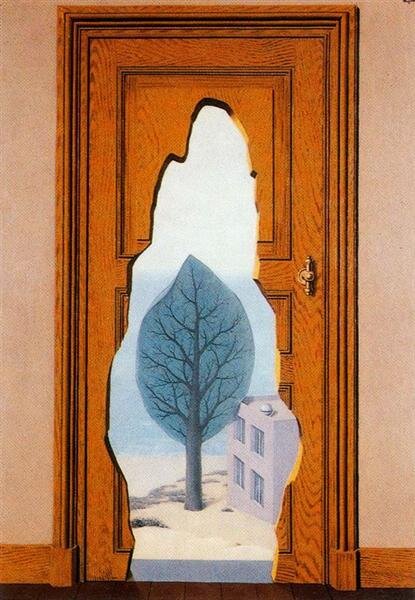

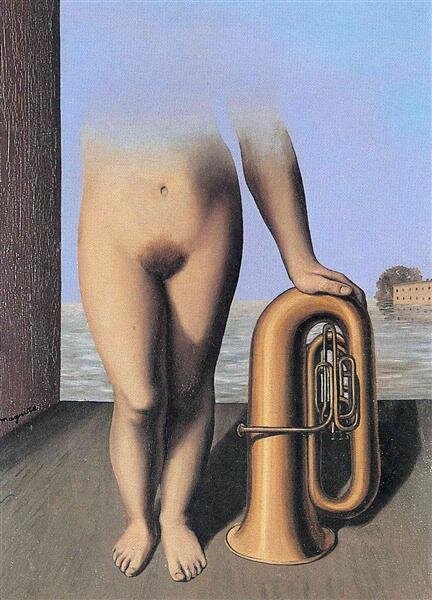

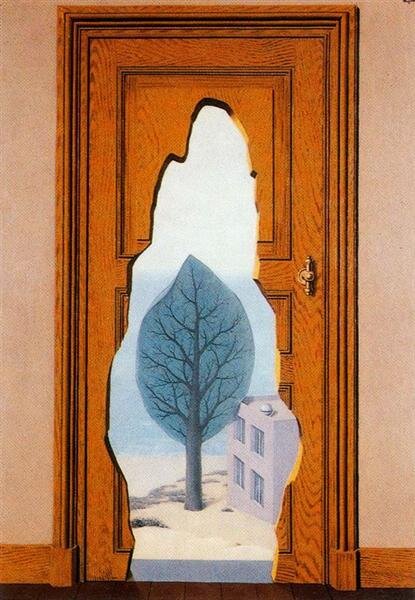

Rene Magritte, 1935; Brussels, Belgium, Surrealism: Robert Giron Collection, Brussels, Belgium

Adriaen de Vries (Netherlandish, The Hague, Prague), ca. 1627, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, public domain

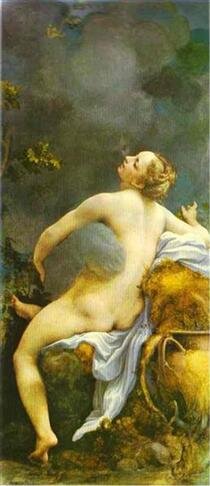

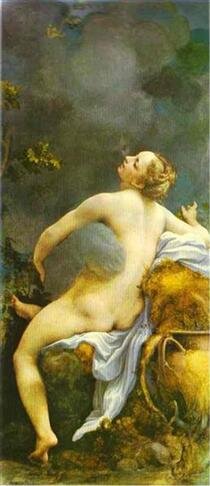

Correggio, 1531 - 1532, Mannerism (Late Renaissance), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

Titian, c. 1553, Apsley House, Stratfield Saye Preservation Trust (Wellington Collection

image: Wikipedia

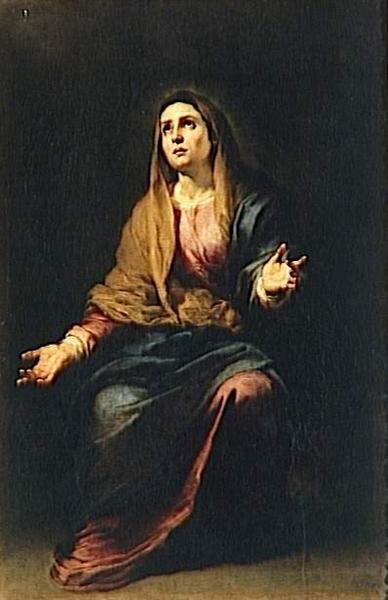

Bernardo Strozzi, c.1640 - c.1644, Baroque: National Museum, Poznań, Poland

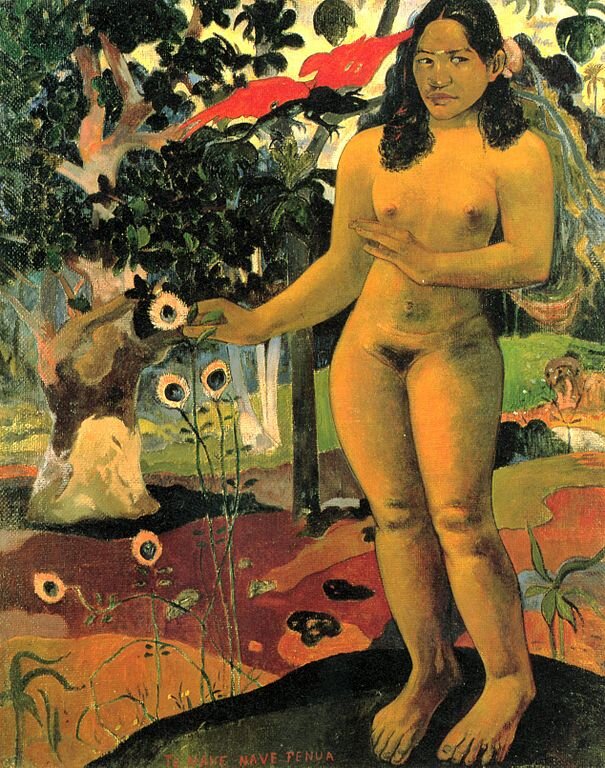

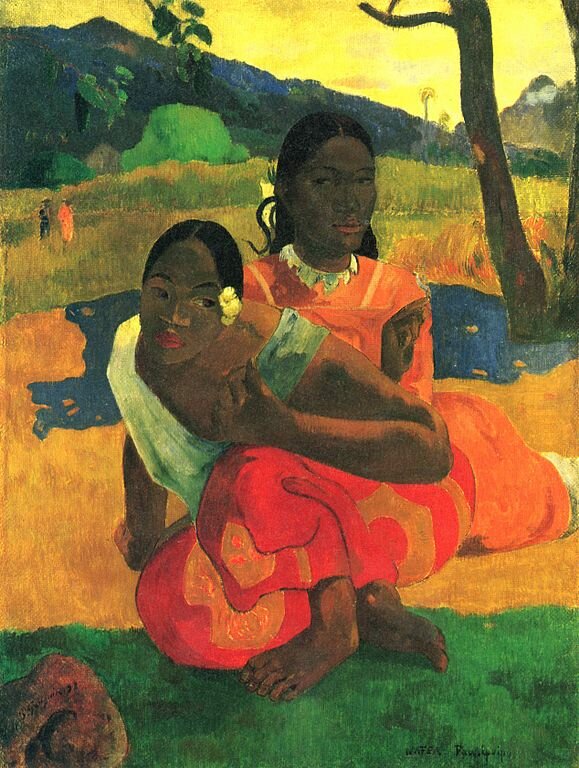

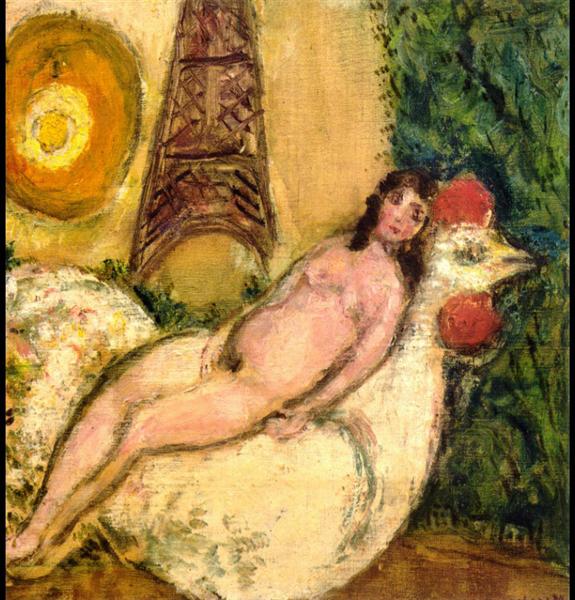

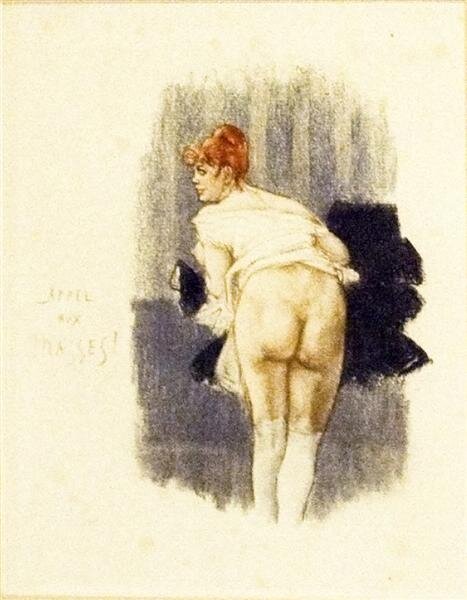

Paul Gauguin, 1890 - 91: Chrysler Museum of Art

The model was Juliette Huet, who became Gauguin's mistress and bore him a daughter.

Edouard Manet, 1863, Musée d'Orsay, Paris, France

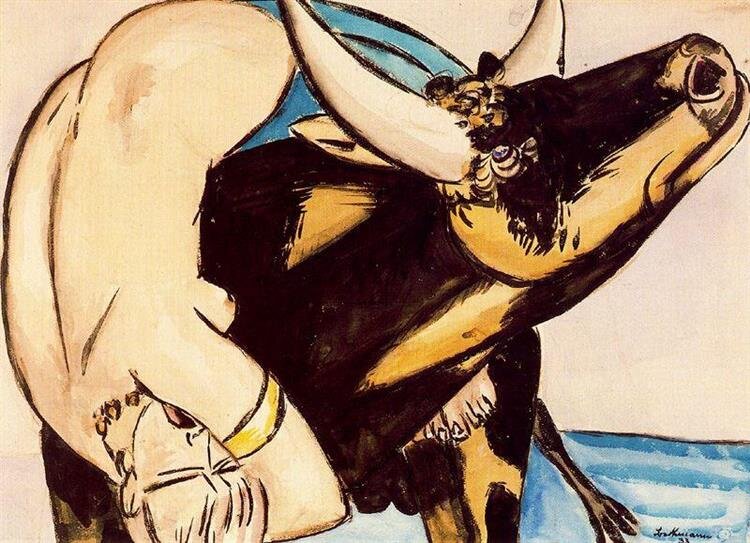

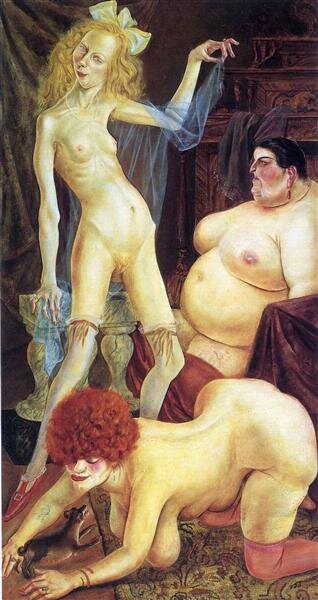

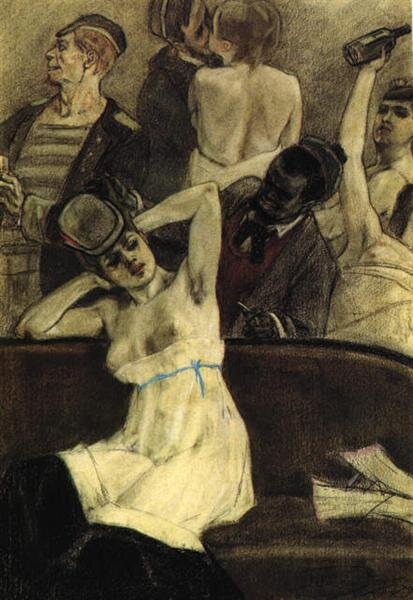

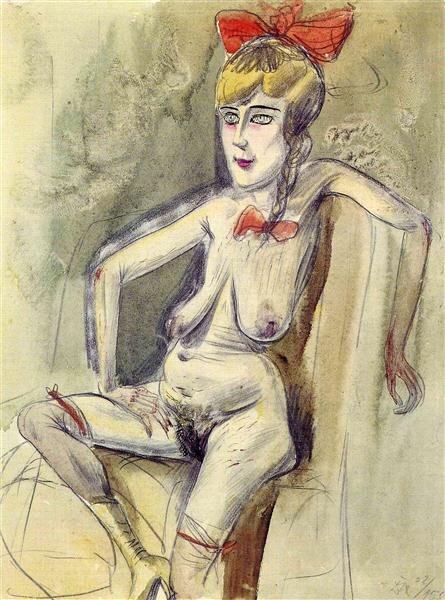

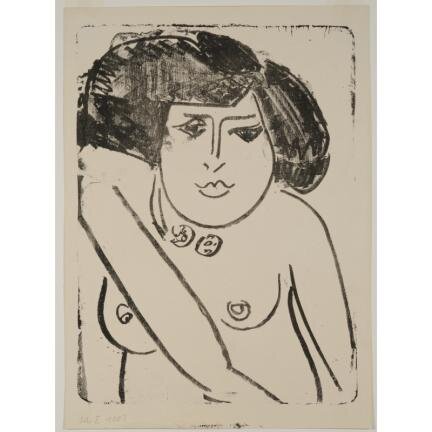

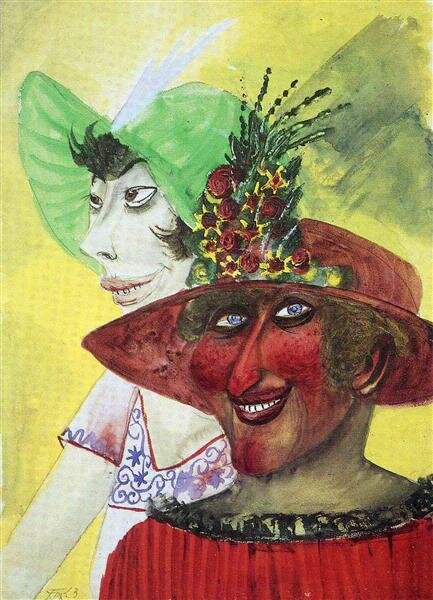

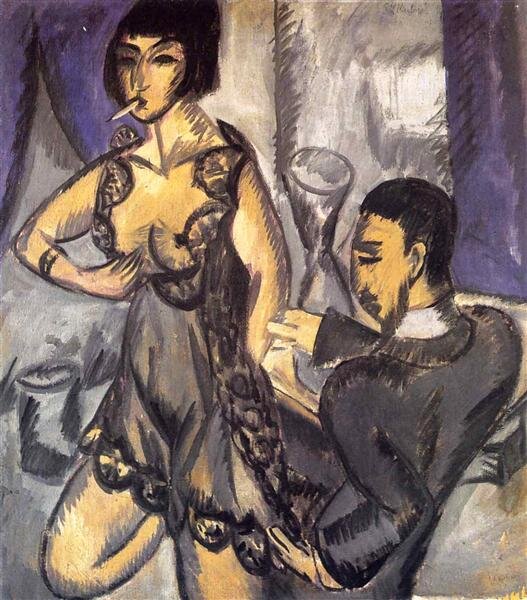

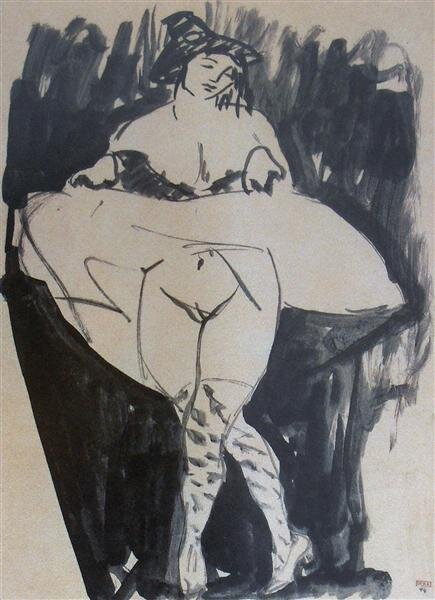

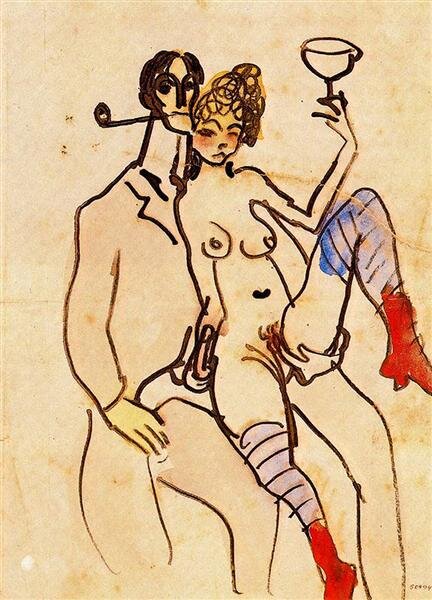

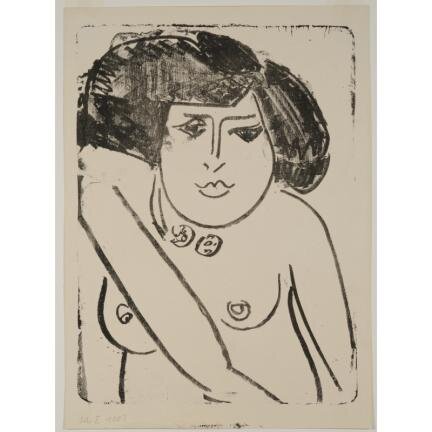

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, 1910, McMaster Museum of Art

Dimensions: Image: 38 x 28.1 cm (14 15/16 x 11 1/16 in.) Support: 42.2 x 30.7 cm (16 5/8 x 12 1/16 in.)

Medium: Lithograph on paper

Edgar Degas, ca. 1896–1911 (cast ca. 1919–26): Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Thannhauser Collection, Gift, Justin K. Thannhauser, 1978

MEDIUM: Bronze

DIMENSIONS: 14 x 14 1/8 x 9 1/4 inches (35.6 x 35.9 x 23.5 cm)

“Edgar Degas’s penetrating and sometimes disturbing depictions of late 19th-century Parisian society are as much innovative explorations of movement and pictorial space as they are portrayals of contemporary life. Degas was from a privileged background, born of a well-to-do family in Paris. After studying law briefly, he turned to art in 1855, attending the École des Beaux-Arts for a time. While he became associated with the Impressionists, Degas belonged to a slightly older generation of artists, which is apparent in the naturalist style of his early portraits and interiors. But, his quintessential works date from the Impressionist decades of the 1870s and 1880s. Like his cohorts, he cast his gaze upon Paris’s electrifying society of spectacle, painting scenes of the café-concert, the opera, and the races. He also looked to those living on the fringes of this world: alienated people drinking absinthe, laundresses, milliners, and prostitutes. Perhaps, most recognizable are his ballerinas, seen in dance classes, at rest, rehearsing, and performing.

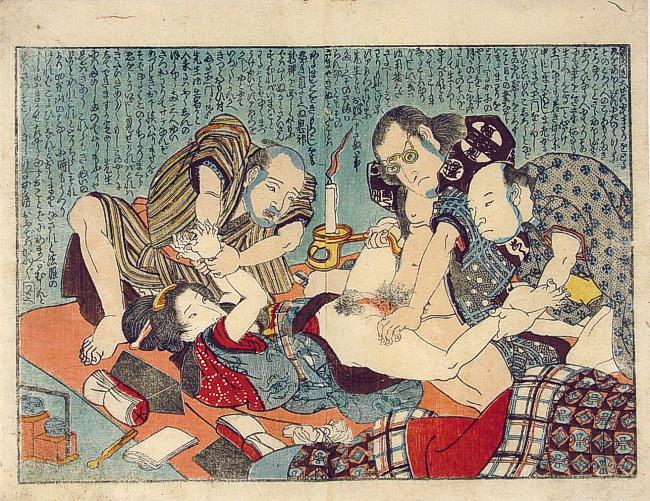

Degas’s formal investigations, however, remained paramount, and his subjects, who often seem caught unaware from unusual angles in awkward poses, are vehicles for these explorations. Blurred action and the dramatic cropping of figures or forms reveal conventions adopted from photography (which he also practiced), signaling the instantaneity that the Impressionists embraced. The cropping, together with his incongruous compositional constructions, was also influenced by the non-illusionistic treatment of space and form of Japanese prints, which had gained popularity in France during the 1860s.

In the mid-1880s, his vision began to fail and the more forgiving medium of pastel became increasingly important to the artist, who fully exploited its soft, blurred contours and coloristic effects. Likewise, the medium of sculpture allowed Degas to use his hands as his eyes in modeling the pliant wax. These sculpted studies of motion parallel contemporaneous examinations of locomotion by photographer Eadweard Muybridge, whose photographs Degas knew. Both Dancers in Green and Yellow and Seated Woman, Wiping Her Left Side date from this period. While each work represents a certain type of exploited lower-class woman—ballerinas often relied upon the patronage of their wealthy, male admirers, while the nude woman washing in a prosaic pose was a prostitute—these works are primarily examples of his lifelong interest in gesture and movement. His deteriorating eyesight eventually forced Degas to cease making art sometime between 1910 and 1912.”

Anna Gaskell, 1998, Chromogenic print, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Purchased with funds contributed by the Photography Committee, 2000

Anna Gaskell crafts foreboding photographic tableaux of preadolescent girls that reference children’s games, literature, and psychology. She is interested in isolating dramatic moments from larger plots such as Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, visible in two series: wonder (1996–97) and override (1997). In Gaskell’s style of “narrative photography,” of which Cindy Sherman is a pioneer, the image is carefully planned and staged; the scene presented is “artificial” in that it exists only to be photographed. While this may be similar to the process of filmmaking, there is an important difference. Gaskell’s photographs are not tied together by a linear thread; it is as though their events all take place simultaneously, in an ever-present. Each image’s “before” and “after” are lost, allowing possible interpretations to multiply. In untitled #9 of the wonder series, a wet bar of soap has been dragged along a wooden floor. In untitled #17 it appears again, forced into a girl’s mouth, with no explanation of how or why. This suspension of time and causality lends Gaskell’s images a remarkable ambiguity that she uses to evoke a vivid and dreamlike world.

Gaskell’s girls do not represent individuals, but act out the contradictions and desires of a single psyche. While their unity is suggested by their identical clothing, the mysterious and often cruel rituals they act out upon each other may be metaphors for disorientation and mental illness. In wonder and override, the character collectively evoked is Alice, perhaps lost in the Wonderland of her own mind, unable to determine whether the bizarre things happening to her are real or the result of her imagination. In wonder, Alice’s instability is invoked even at the level of presentation: the varied sizes of the photographs refer to her own growth spurts and shrinking spells. Gaskell’s allusions to Carroll’s story, however, are not always so playful. The seven versions of Alice in override alternate roles as victim or aggressor. They try to control the changes to Alice’s body by literally, physically holding her in place—a potent metaphor for the anxiety and confusion experienced by children on the verge of adolescence. hide (1998) derives from a Brothers Grimm tale of a young woman who disguises herself under an animal pelt so that she might escape her own father’s proposal of marriage. Gaskell addresses this psychologically loaded subject matter with images of girls wandering in a gothic mansion illuminated by candlelight. Here the psyche in question has been fractured and fraught with terror by a perverse father’s look, a voyeuristic gaze.”

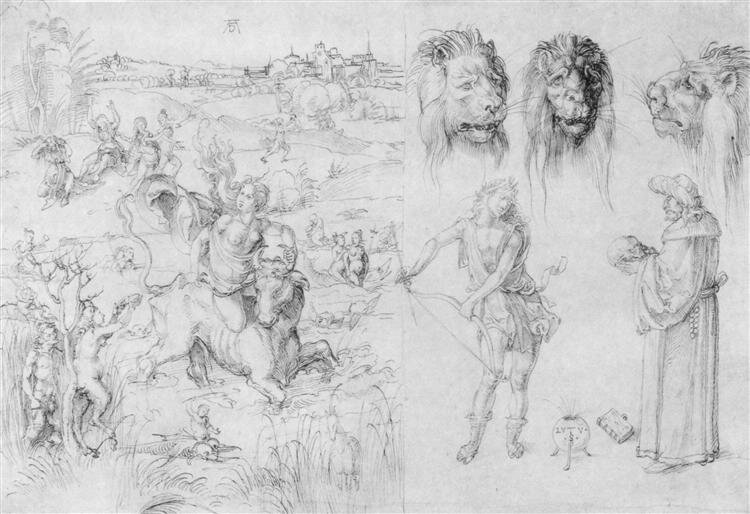

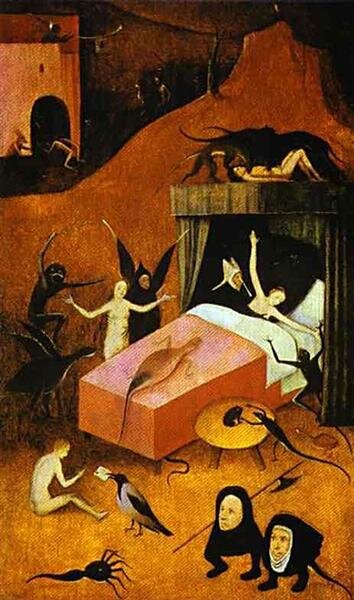

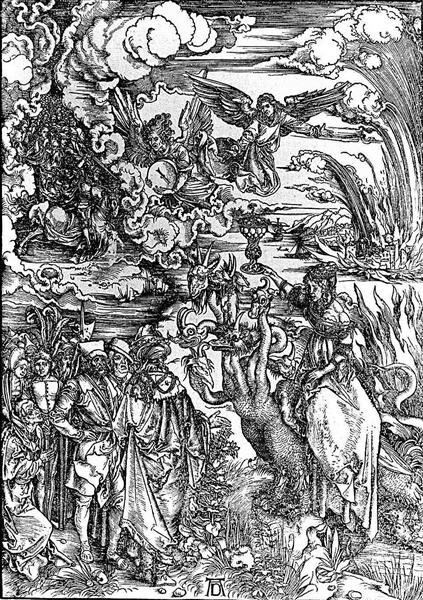

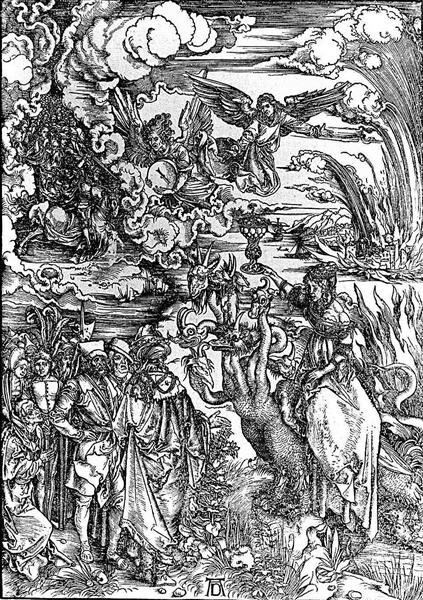

Albrecht Durer, 1497 - 1498, Northern Renaissance: Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe, Germany

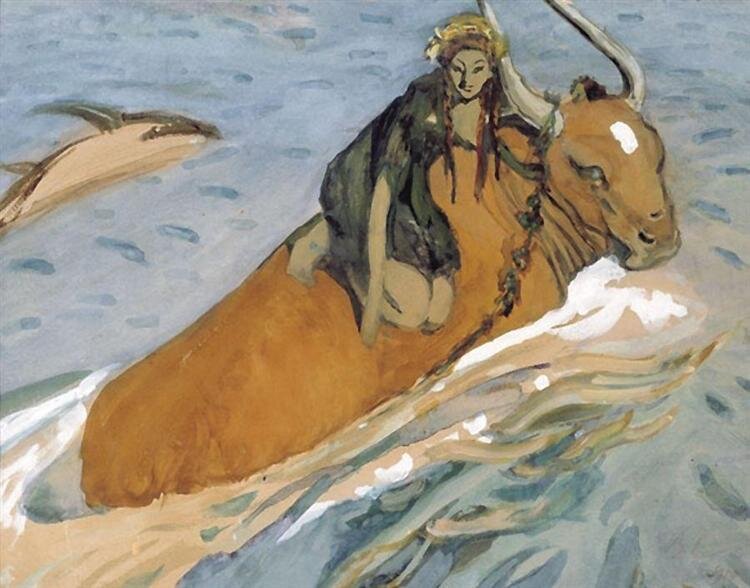

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863): Louvre Museum

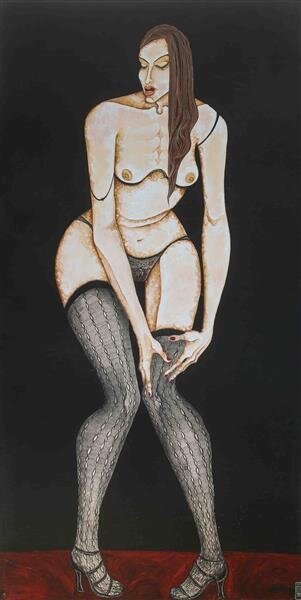

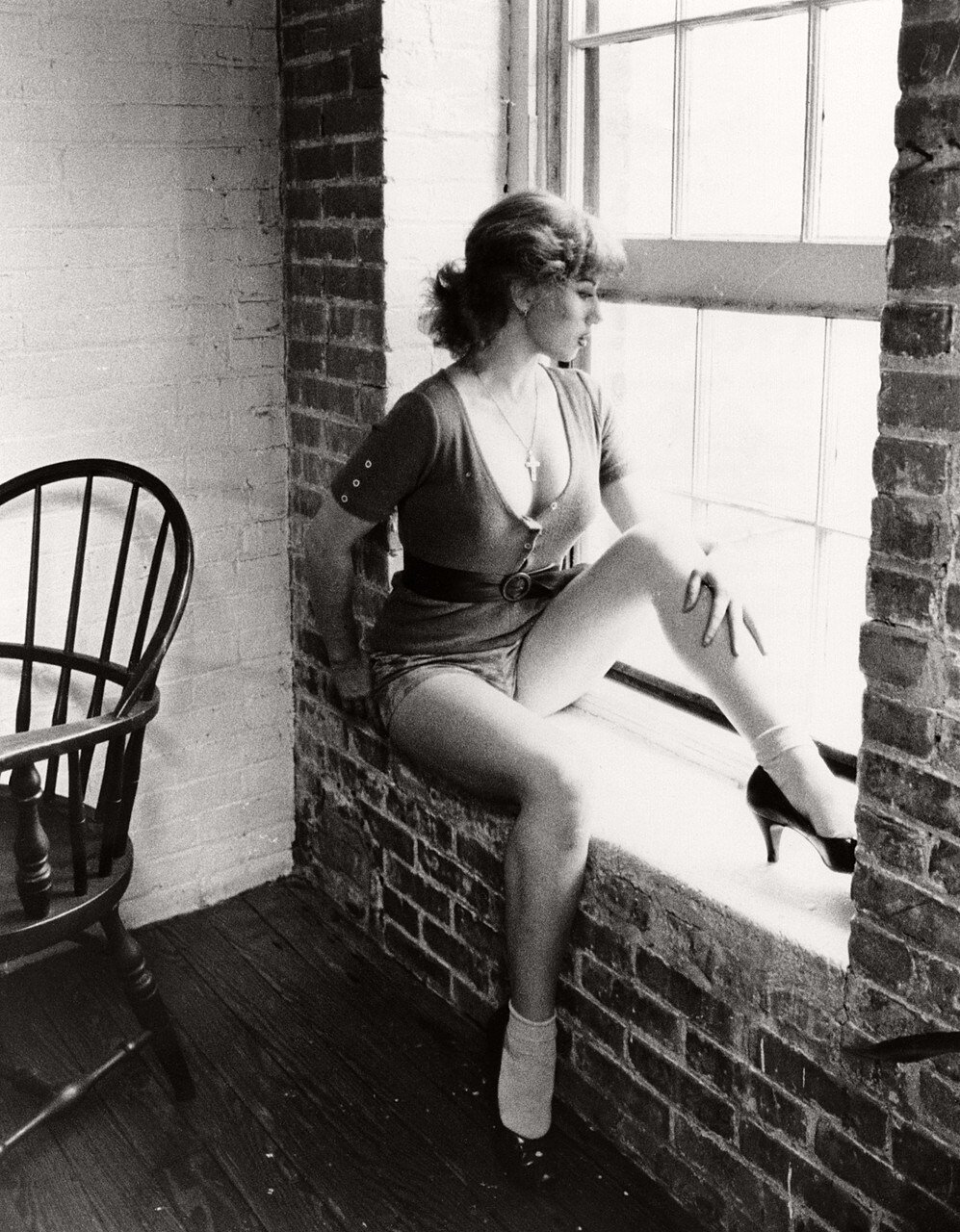

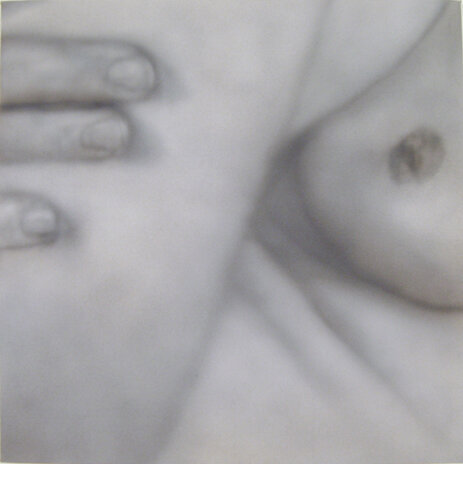

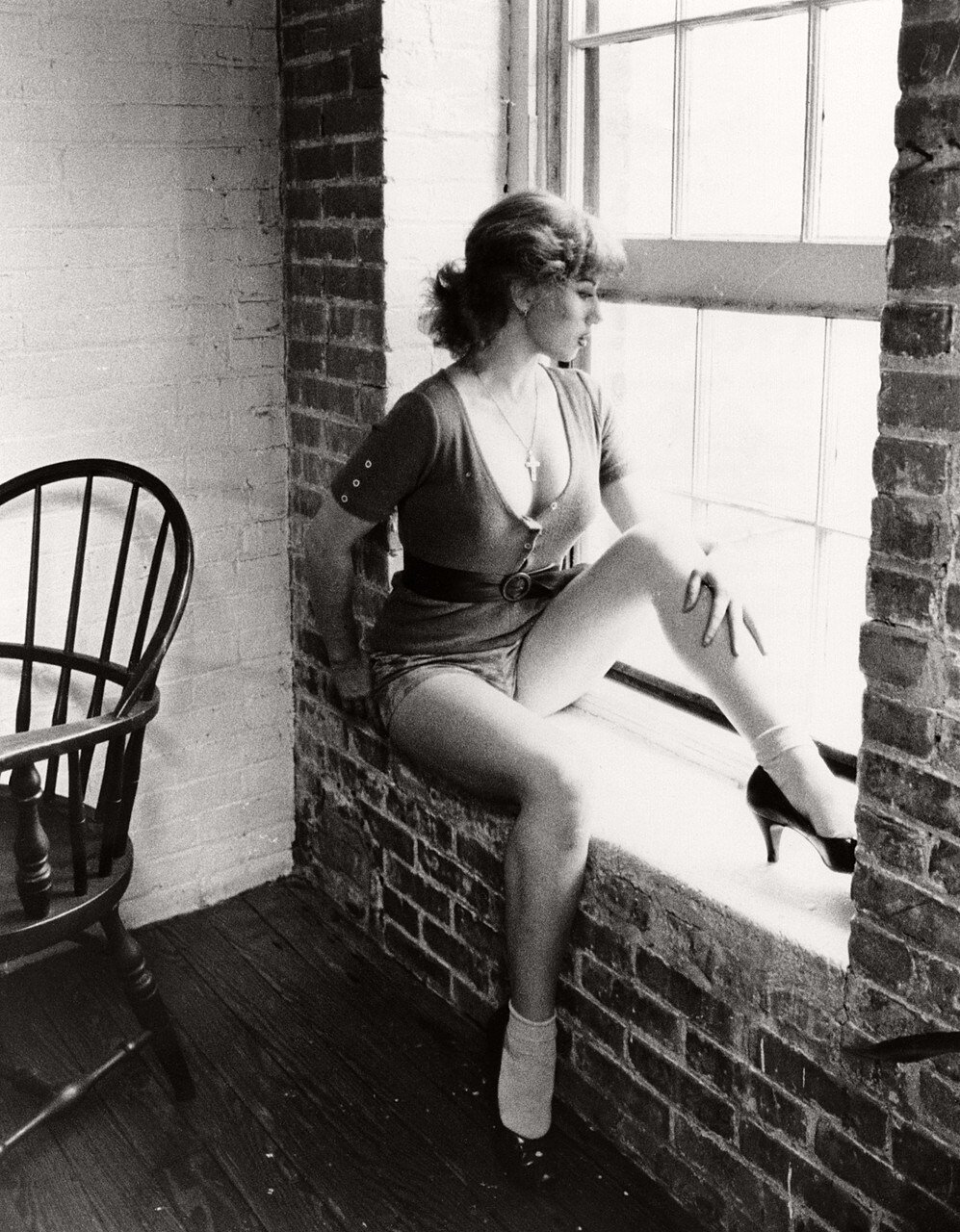

Cindy Sherman, 1978, Gelatin silver print, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Purchased with funds contributed by the International Director's Council and Executive Committee Members: Eli Broad, Elaine Terner Cooper, Ronnie Heyman, J. Tomilson Hill, Dakis Joannou, Barbara Lane, Robert Mnuchin, Peter Norton, Thomas Walther, and Ginny Williams, 1997

Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills (1977–80) have been canonized as a hallmark of postmodernist art, which frequently utilized mass-media codes and techniques of representation in order to comment on contemporary society. In this series of 69 black-and-white photographs, Sherman posed herself in various melodramatic guises that recall the stereotypical feminine characters presented in 8 x 10 publicity stills for B-grade movies from the 1950s and 1960s. The personae she created range from ingenue lost in the big city to martini-wielding party girl to jilted lover to hausfrau. Untitled Film Still, #15 (1978) depicts the tough girl with a heart of gold. Contrary to the media images they appropriate, which may require a transparent sense of realism to sell an illusion, Sherman’s stills have an artifice that is heightened by the often visible camera cord, slightly eccentric props, unusual camera angles, and by the fact that each image includes the artist, rather than a recognizable actress or model.

In the early 1980s Sherman continued to explore stereotypes of femininity and female representation found in popular culture, such as the centerfold format of pornographic magazines. She also began to use color in her work; her painterly sensibility is apparent in Untitled, #112 (1982) and subsequent photographs. Untitled, #112 is also one of the first images in which the artist portrays a more masculine identity. This gender ambiguity, along with the way the unusually lit figure emerges from the black background, yields an unsettling sensation. These effects become ominous and even frightening in later works in which Sherman portrays more disheveled and malign characters.

Untitled, #167 (1986) is from Sherman’s Disasters series, which directly investigates grotesque and disgusting subject matter. The sense of foreboding elicited by earlier works is more overt, suggesting the terror of horror films (a genre that significantly focuses on female victims). Untitled, #167 depicts the scene of a gruesome crime. Emerging from the dirt are the nose, lips, and red-painted fingertips of a blonde, apparently female, victim. A discarded Polaroid photographic sheath suggests documentation (either by a police officer or perhaps the villain, whose reflection appears in an open makeup compact), and obliquely implicates the artist as photographic voyeur. The very darkness of the image and the reflectiveness of the photograph’s surface make it difficult for the viewer to scrutinize the scene. Untitled, #167 foreshadows Sherman’s use of prosthetic body parts in her later works, as well as the gradual elimination of her own likeness.

Jennifer Blessing

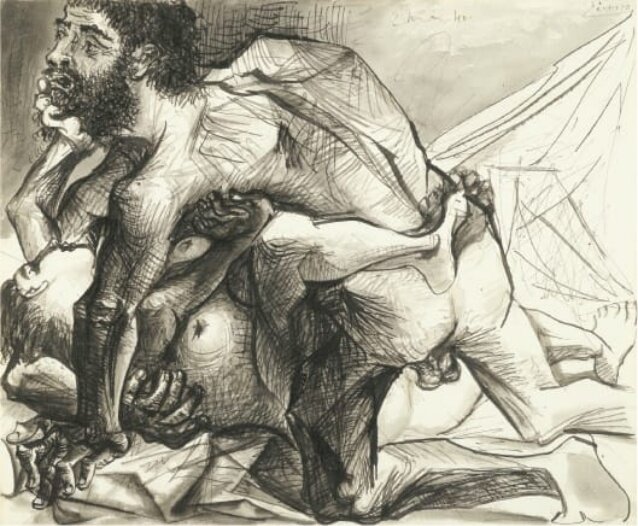

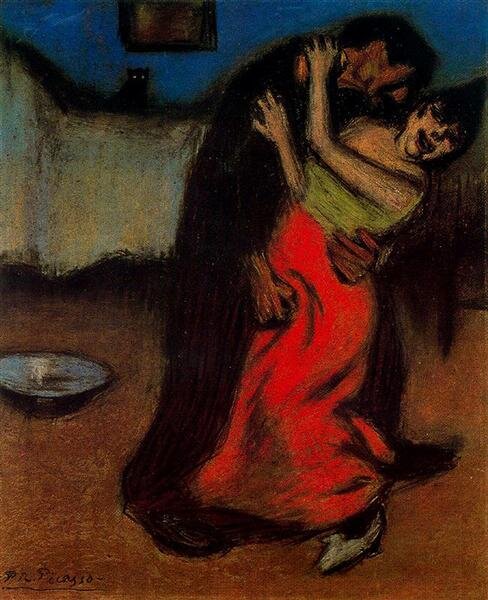

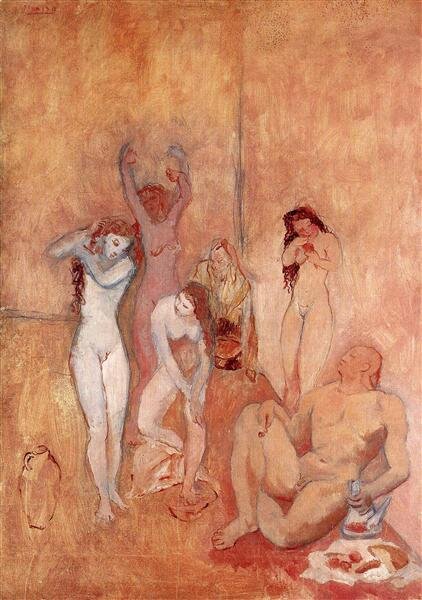

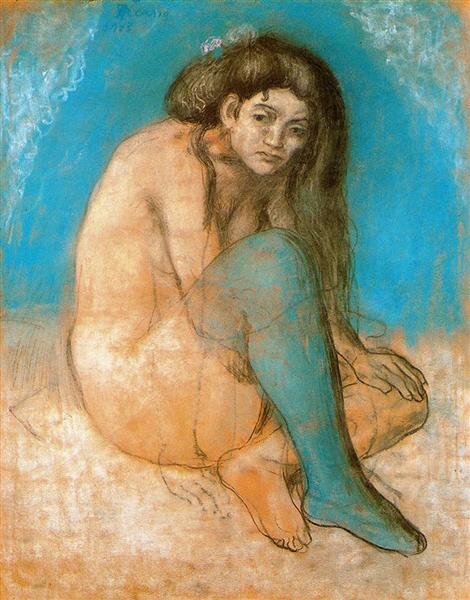

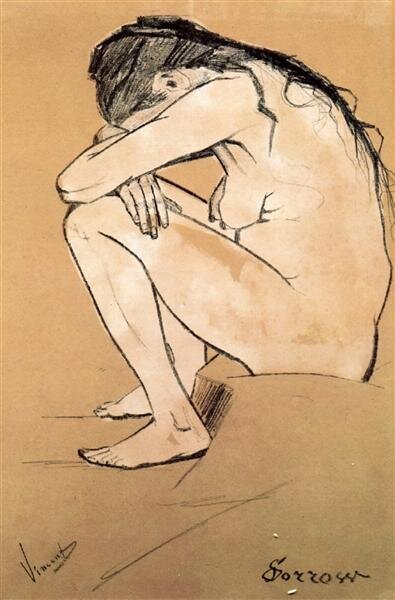

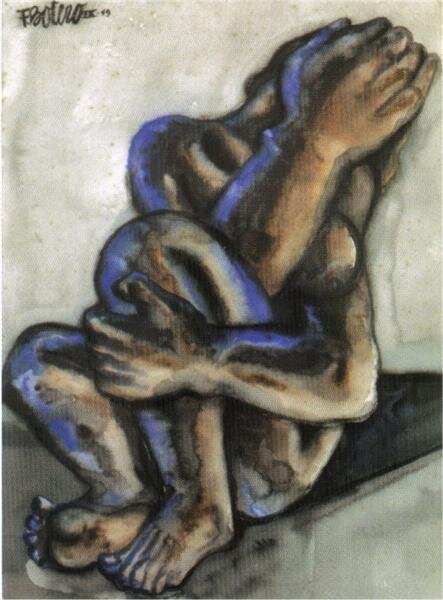

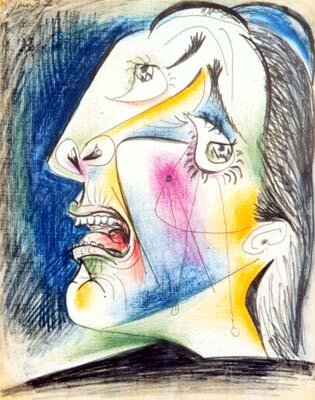

Pablo Picasso, c.1903, Expressionism, Museu Picasso, Barcelona, Spain

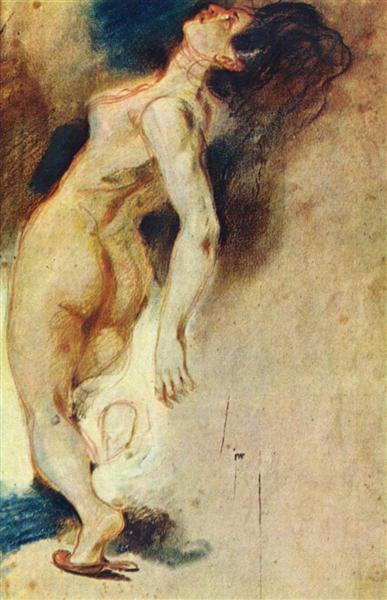

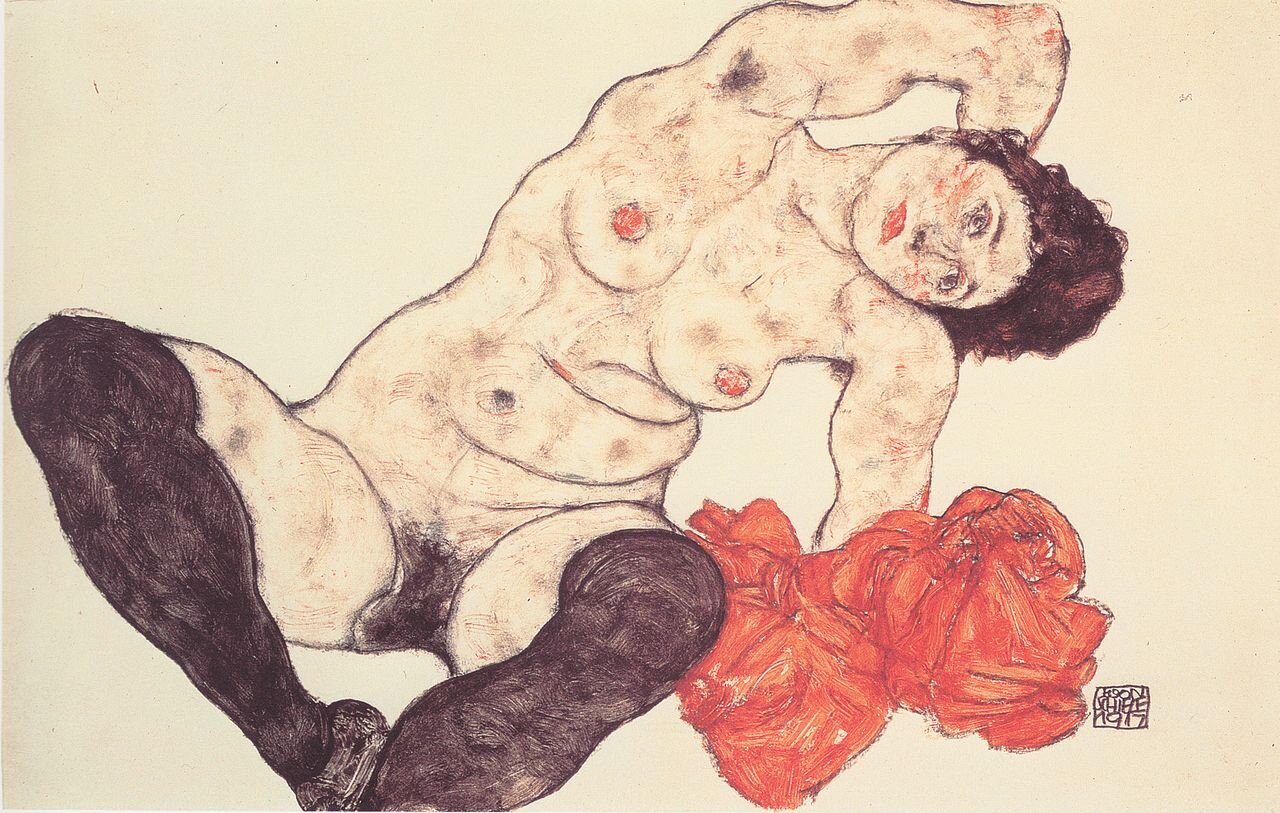

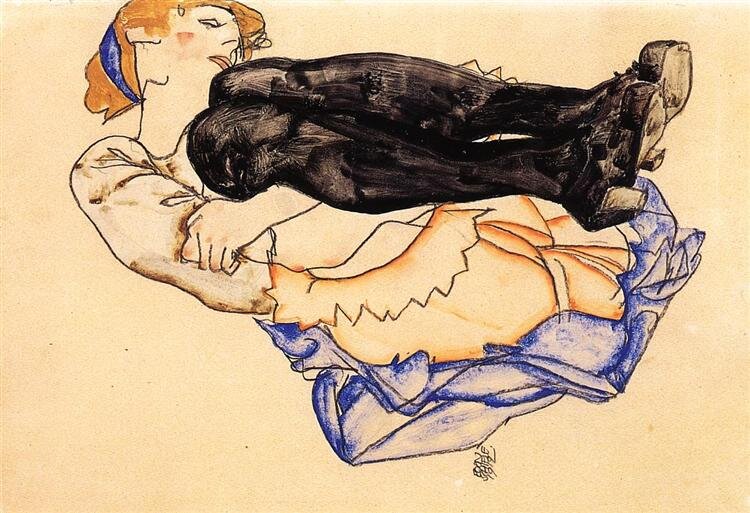

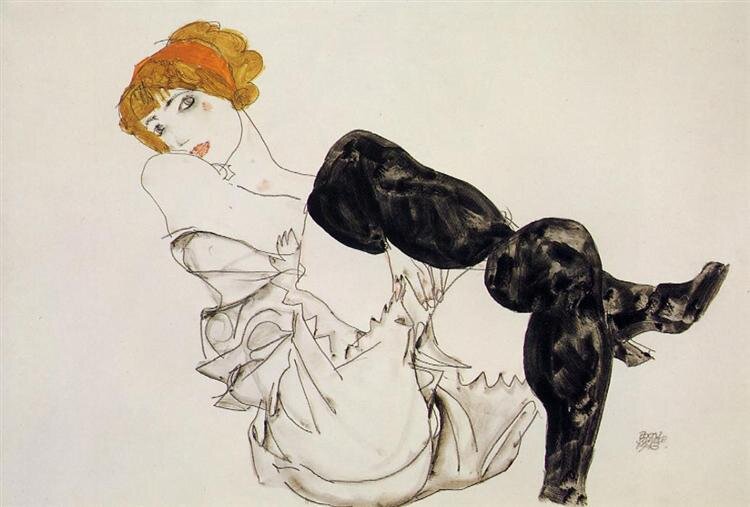

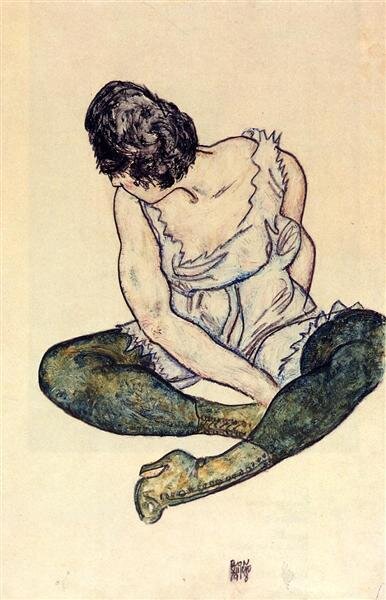

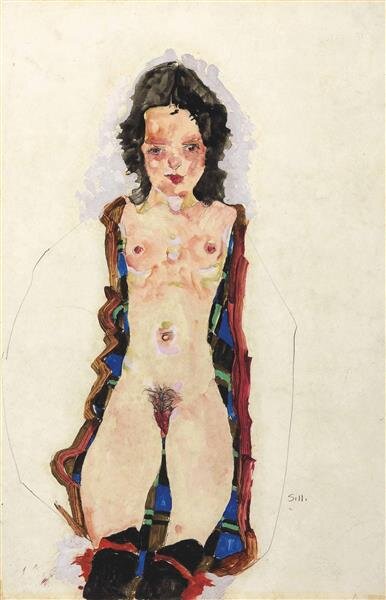

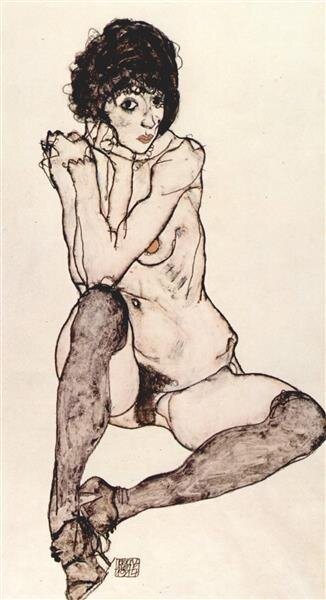

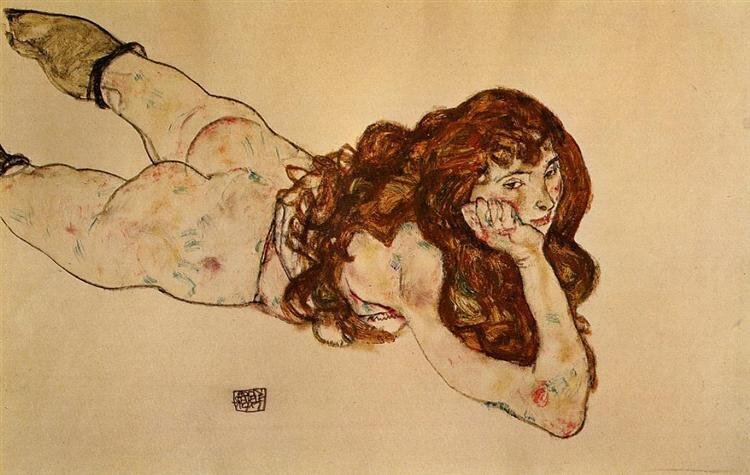

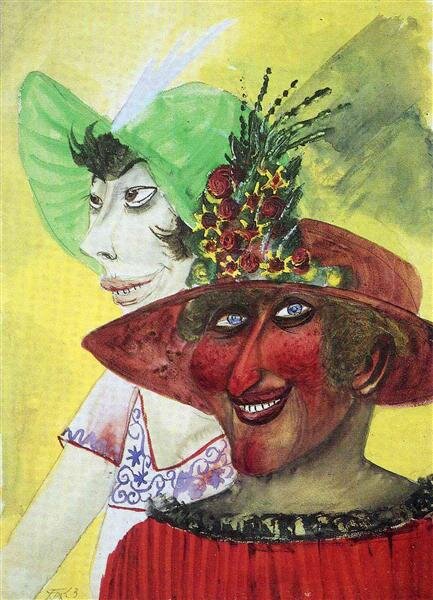

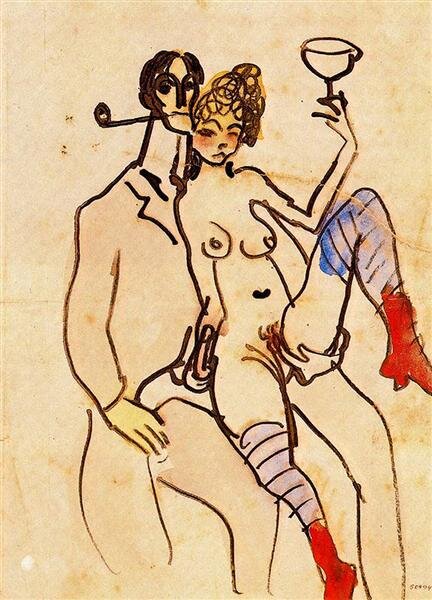

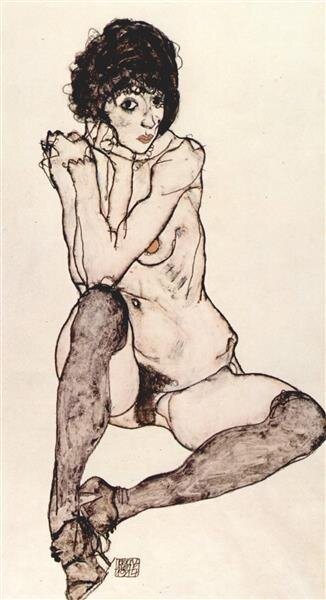

Egon Schiele,1914, Expressionism, Albertina, Vienna, Austria

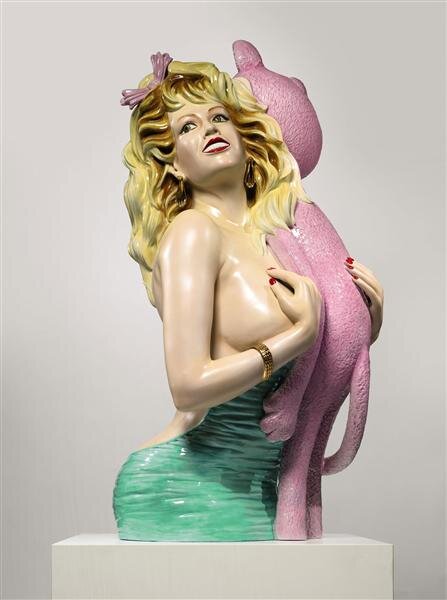

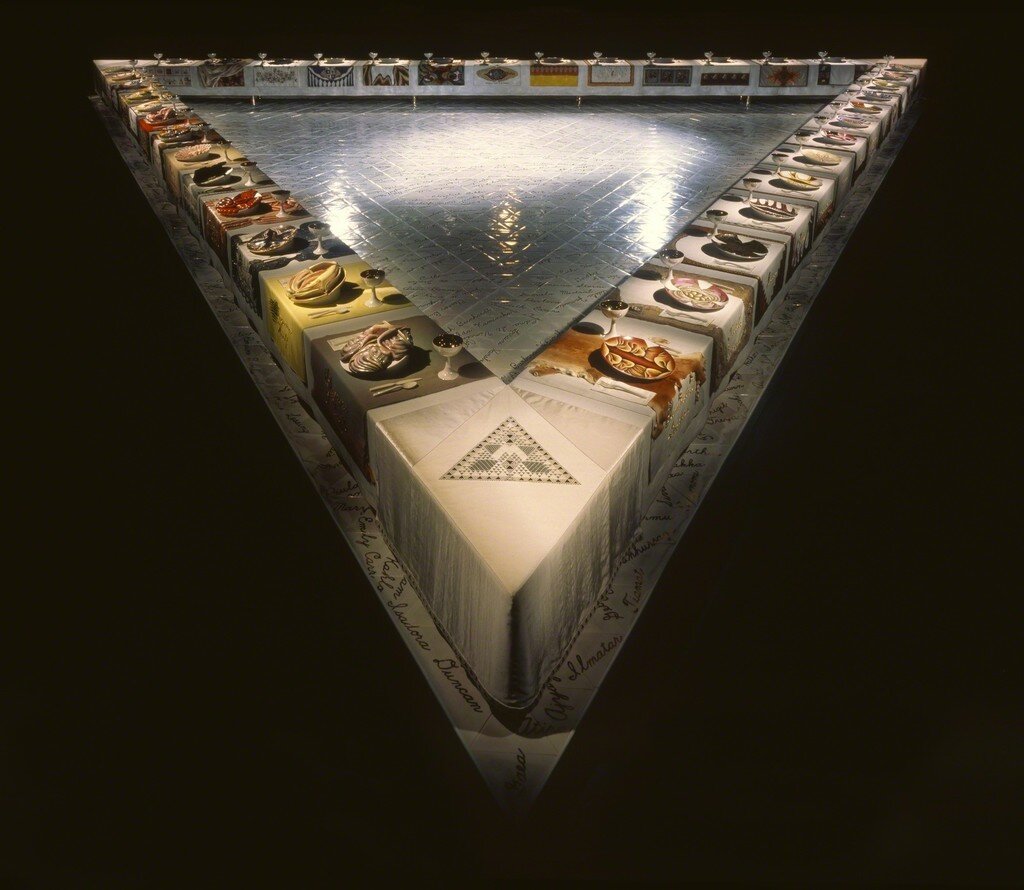

Runner: 54 x 33 1/2 in. (137.2 x 85.1 cm) Plate:14 1/2 x 14 3/16 x 2 in. (36.8 c 36 x 5.1 cm)

Brooklyn Museum

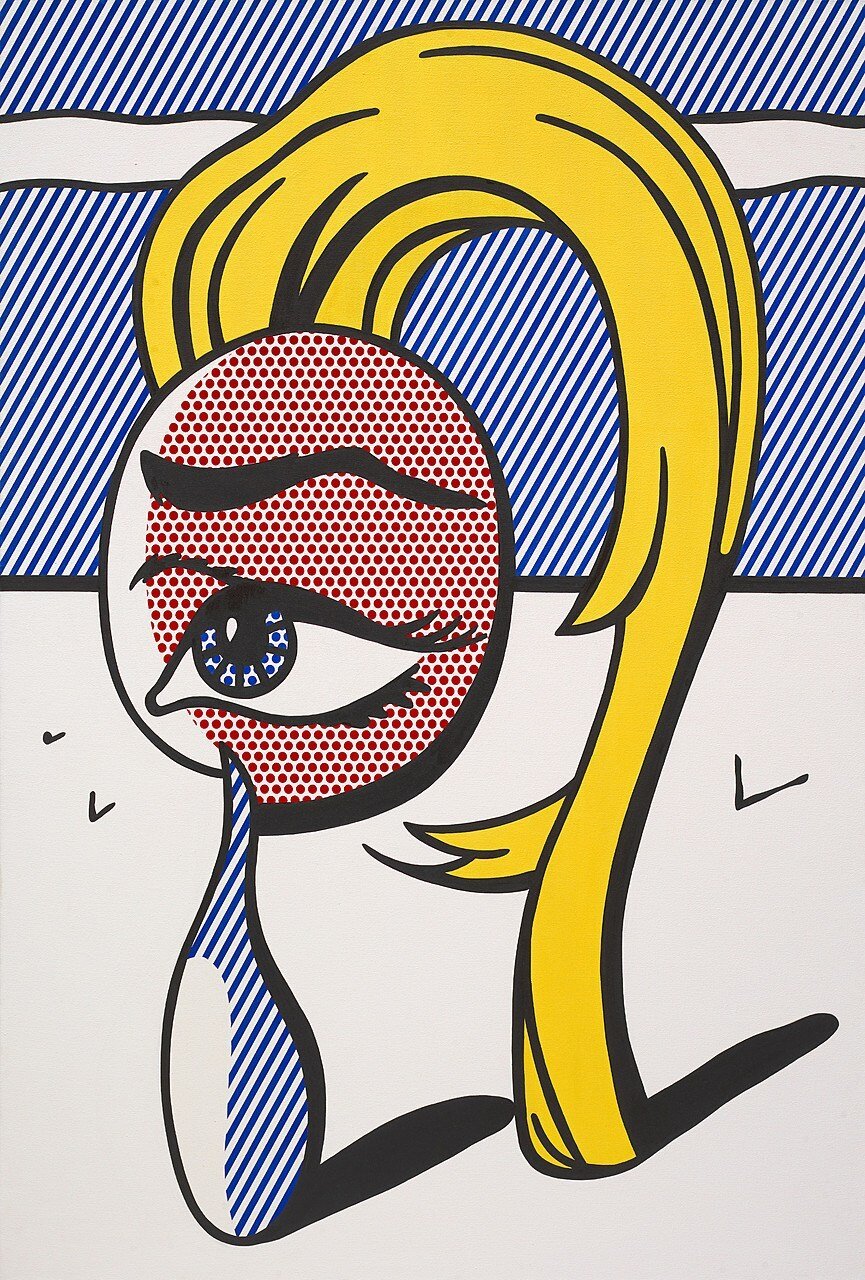

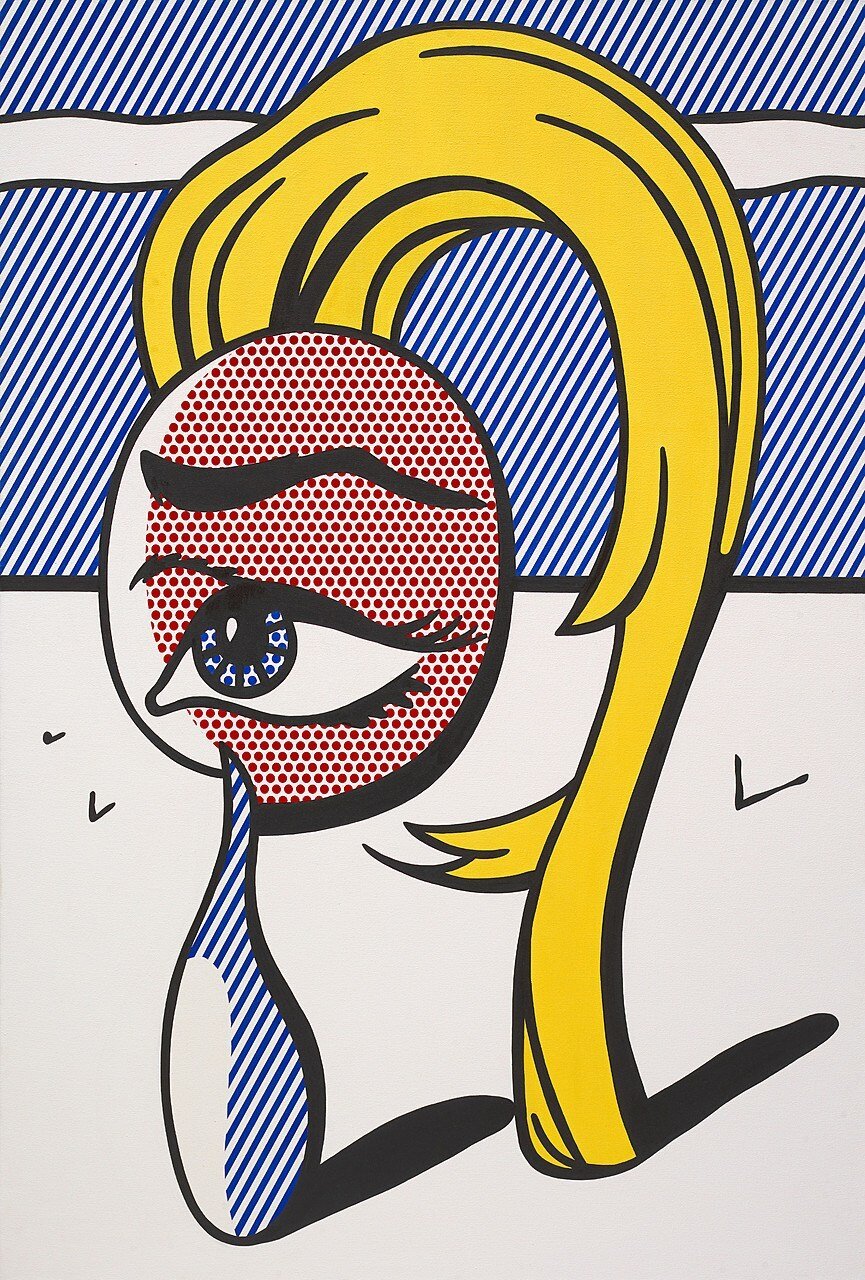

Roy Lichtenstein, 1977, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Gift of the artist, by exchange, 1980

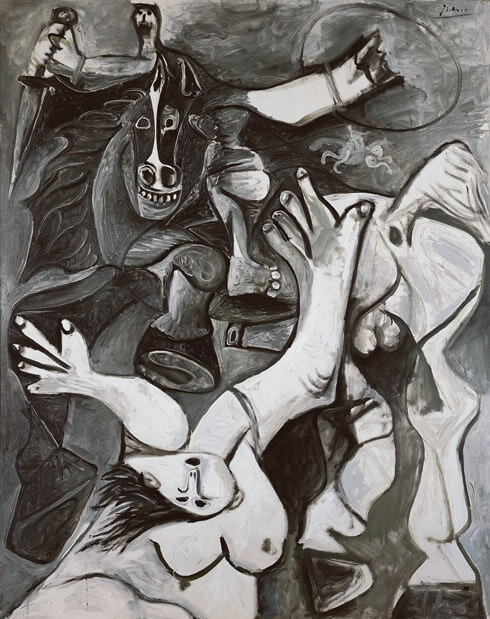

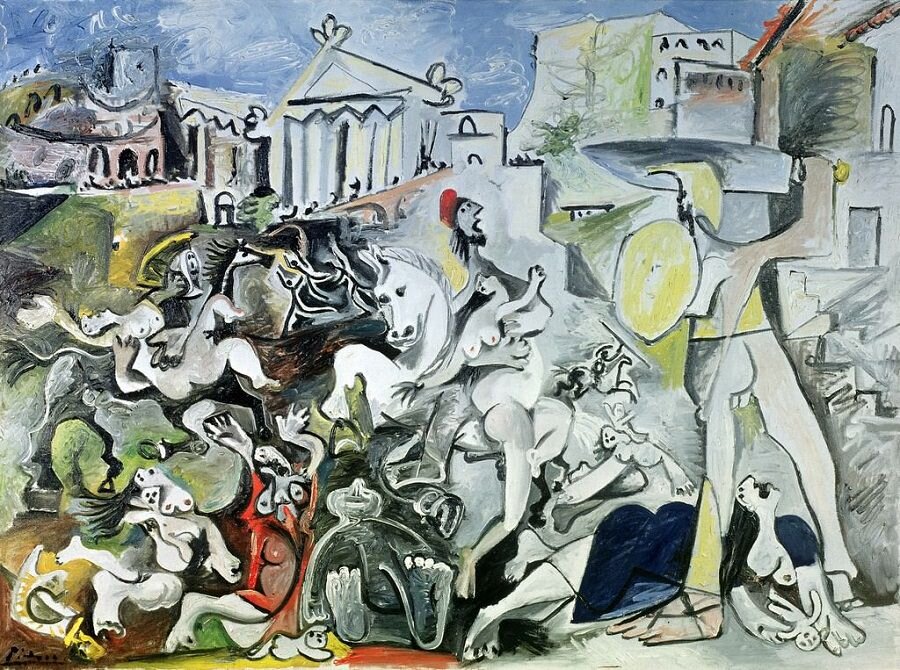

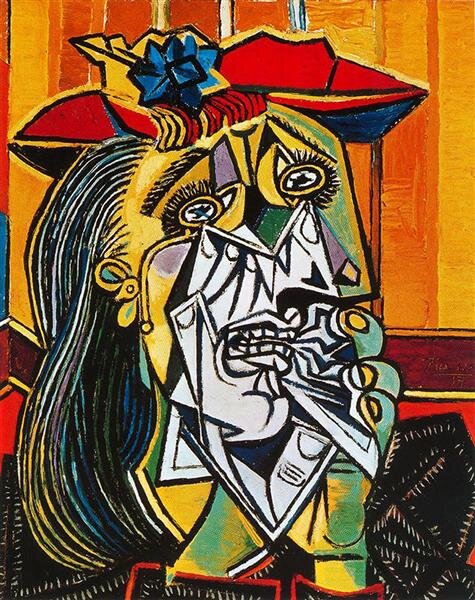

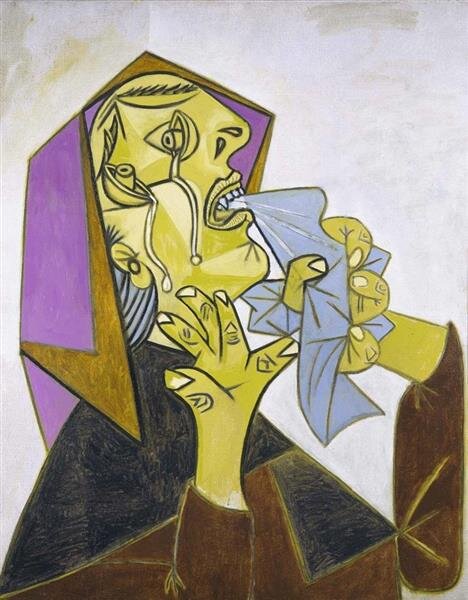

Pablo Picasso, 1937, Cubism, Surrealism: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (MNCARS), Madrid, Spain

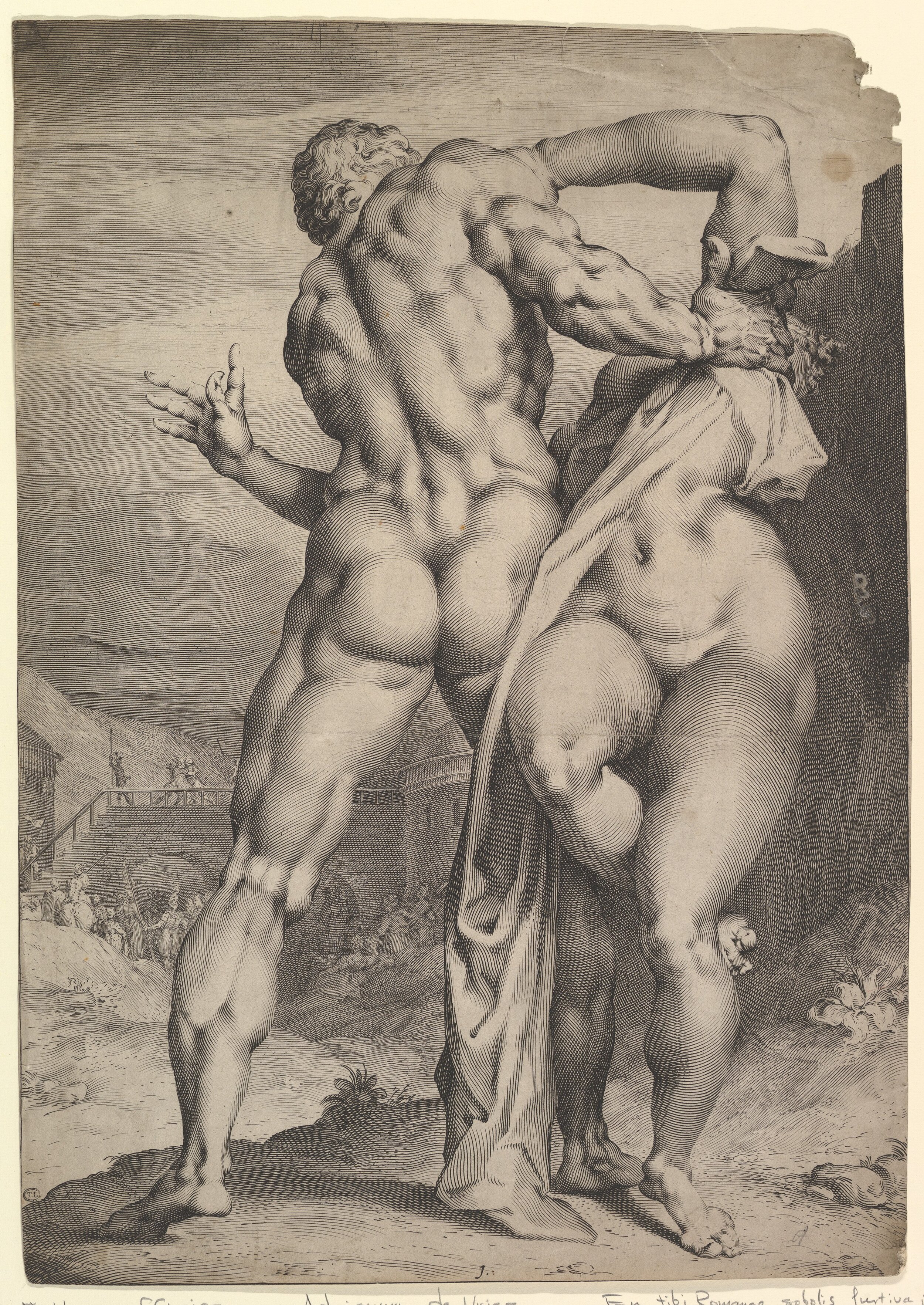

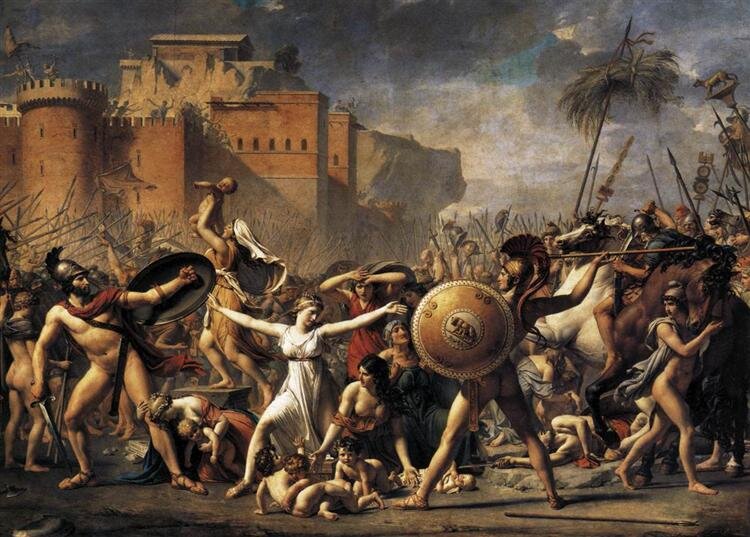

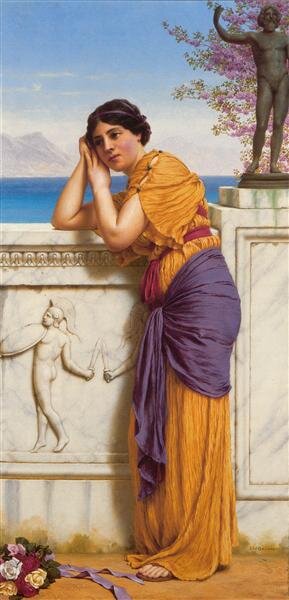

Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640): Louvre Museum