Musee des Beaux Arts de Montreal

George Segal

New York 1924 – South Brunswick, New Jersey, 2000

1993

Plaster, wood, acrylic paint, various materials

244 x 363 x 217 cm

Purchase, Horsley and Annie Townsend Bequest, inv. 1994.1a-j

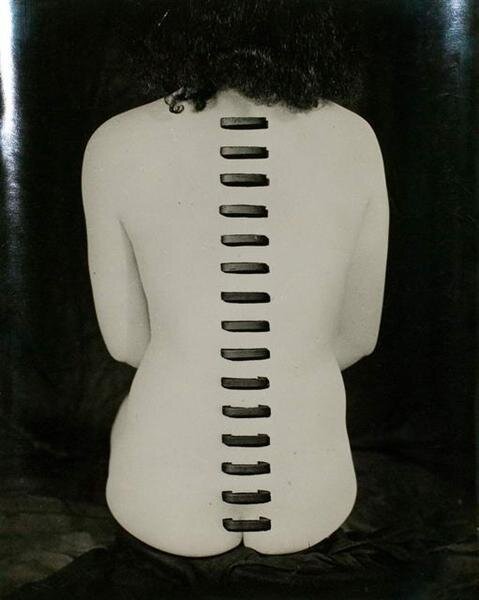

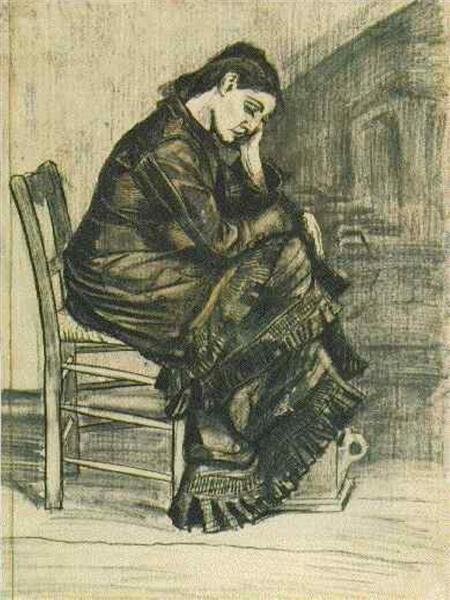

Although its earliest phases have been associated with the Pop Art movement, the work of Segal actually falls within a humanist tradition. His casts of people in everyday environments are intended as a moving commentary on the alienation experienced by human beings. In the early 1980s, Segal dropped colour and realist props from his compositions and began to paint his backgrounds black. "I am looking a lot at Rembrandt, I am looking at Old Master paintings that are really a flat canvas that magically has been painted to resemble a three-dimensional sculpture. And I am trying the reverse. I am making a three-dimensional sculpture to see what happens if I can indicate some of those strange lights and darks that are purely imaginative." First exhibited in 1993 at the Sidney Janis Gallery in New York, this work presents itself simultaneously as a realist scene and as an allegory. Seated in harsh light in a world completely black, her slightly bent back turned towards the viewer, this women is shown at a mundane moment of the day - in her extreme exhaustion, she embodies the weariness of the world.

© The George and Helen Segal Foundation / SODRAC, Montréal / VAGA, New York (2020)

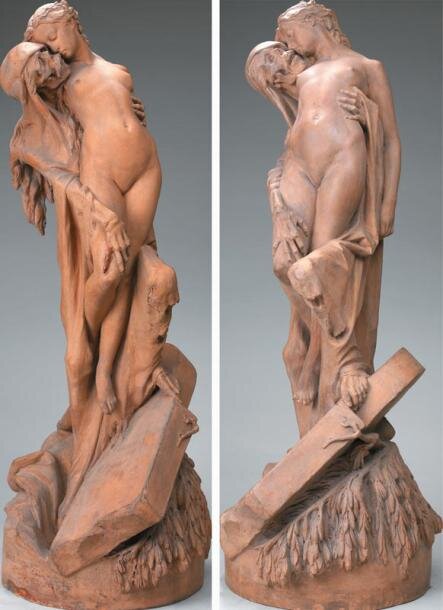

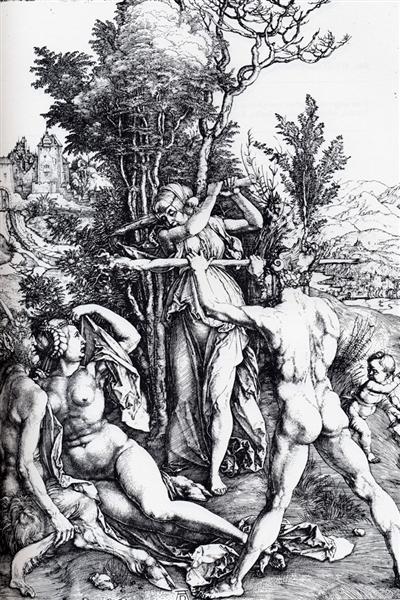

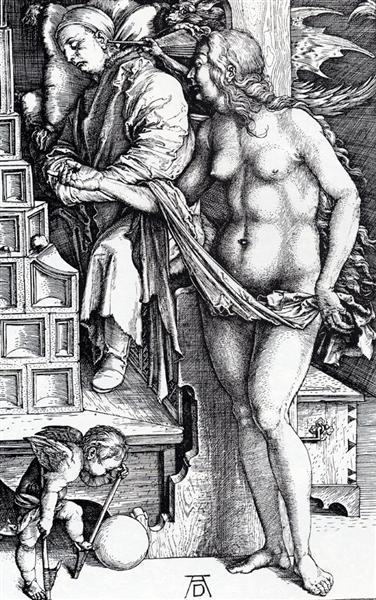

Rembrandt, 1631

Andromeda is Rembrandt's first full length mythological female nude history painting inspired by a story in Ovid's Metamorphoses

Musee des Beaux Arts de Montreal

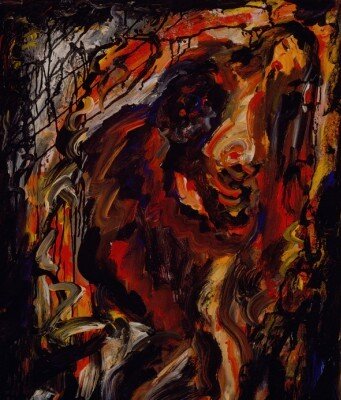

Paul-Émile Borduas

Saint-Hilaire, Quebec, 1905 – Paris 1960

1941-1946

Oil on canvas

70.7 x 63.5 cm

Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Max Stern, inv. 1979.26

© Estate of Paul-Émile Borduas / SOCAN (2020)

Alberto Giacometti, 1932 (cast 1940), Bronze, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 1976

DIMENSIONS: 9 1/8 x 35 1/16 x 23 5/8 inches (23.2 x 89.1 x 60 cm)

“In a group of works made between 1930 and 1933, Alberto Giacometti used the Surrealist techniques of shocking juxtaposition and the distortion and displacement of anatomical parts to express the fears and urges of the subconscious. The aggressiveness with which the human figure is treated in these fantasies of brutal erotic assault graphically conveys the content. The female, seen in horror and longing as both victim and victimizer of male sexuality, is often a crustacean or insectlike form. Woman with Her Throat Cut is a particularly vicious image: the body is splayed open, disemboweled, arched in a paroxysm of sex and death. Eros and Thanatos, seen here as a single theme, are distinguished and treated separately in two preparatory sketches.

Body parts are translated into schematic abstract forms like those in Cage of 1930–31, which includes the spoon shape of the female torso, the rib and backbone motif, and the pod shape of the phallus. Here a vegetal form resembling the pelvic bone terminates one arm, and a phalluslike spindle, the only movable part, gruesomely anchors the other; the woman’s backbone pins one leg by fusing with it; her slit carotid immobilizes her head. The memory of violence is frozen in the rigidity of rigor mortis. The psychological torment and the sadistic misogyny projected by this sculpture are in startling contrast to the serenity of other contemporaneous pieces by Giacometti, such as Woman Walking.” — Lucy Flint

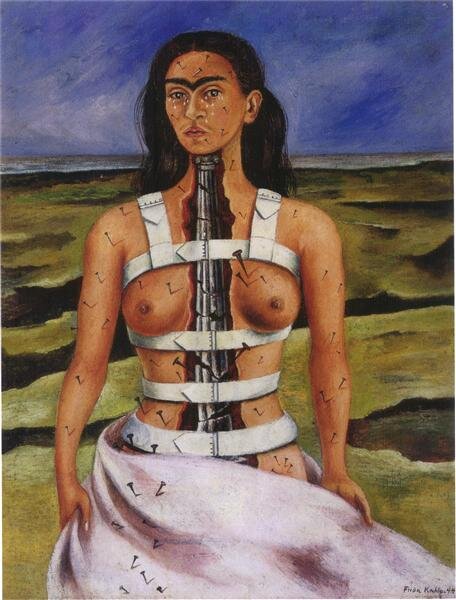

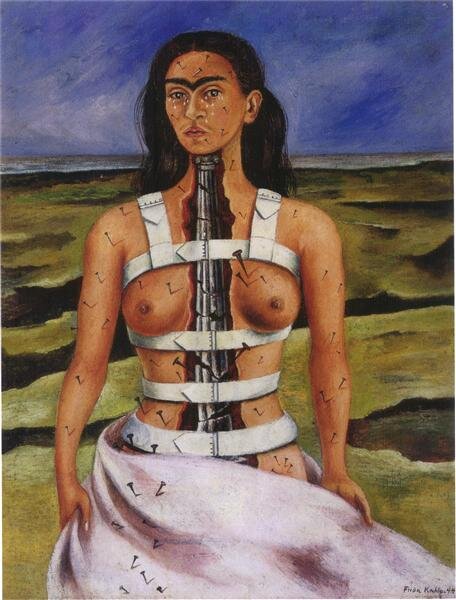

Frida Kahlo, 1944, Naïve Art (Primitivism): Dolores Olmedo Collection, Mexico City, Mexico

Nate Lowman, 2013, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Purchased with funds contributed by David Shuman, 2013

Laced with sardonic humor, Nate Lowman’s paintings, photographs, sculptures, and installations use strategies of aggregation and subtle transformation to unearth narratives buried in our collective psyche. Safe Travels (2013) re-creates nine images from airplane safety guides. Enlarged and stripped of context, the panels are unmoored from their instructional purpose. Images that are meant to do the sober work of preparing passengers for emergencies suddenly appear suffused with unintended humor and suggestions of sexuality and violence. The dishonesty of these calm, idealized images is revealed, as is their ambiguous meaning; Lowman’s arrangement emphasizes the absurdity inherent in sanitized mass visual culture, where real danger or stark reality is often cheerily replaced by more palatable images and stories. Much of Lowman’s work, which includes paintings of smiley faces, bumper stickers, and air fresheners, similarly troubles the seemingly stable and simple meanings of ubiquitous visual signifiers. Lowman is not only interested in cultural semantics, however; he also subtly explores notions of craft. Although even tones and sharp lines give Safe Travels the look of silk screens, they are painstakingly painted by hand. By faithfully re-executing these images in a vaunted artistic medium, Lowman draws attention to the creative work of anonymous graphic artists and the ever-hazy distinction between design and high art.

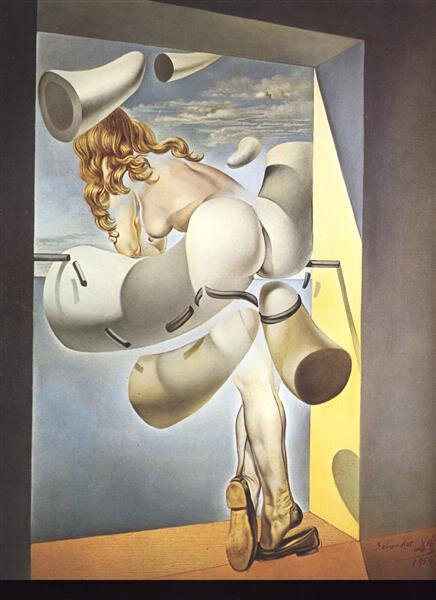

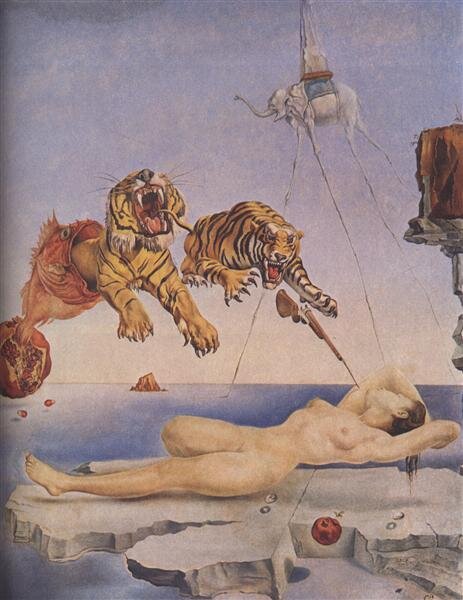

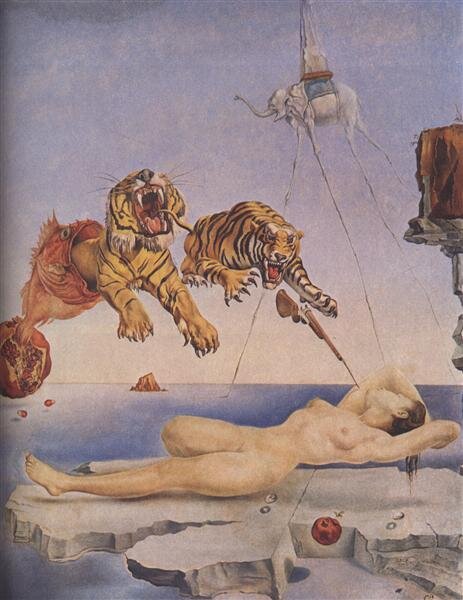

Salvador Dali

1944

Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid, Spain

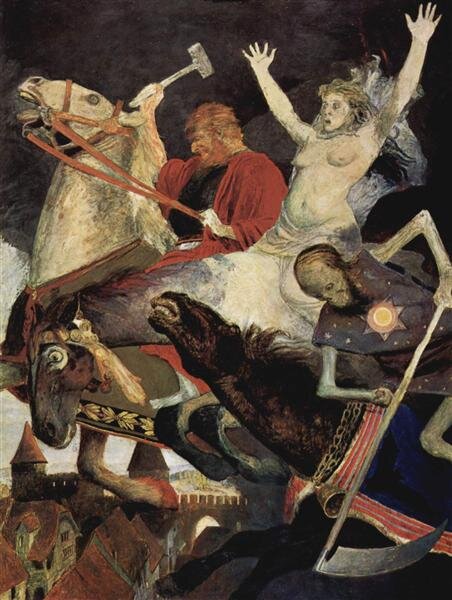

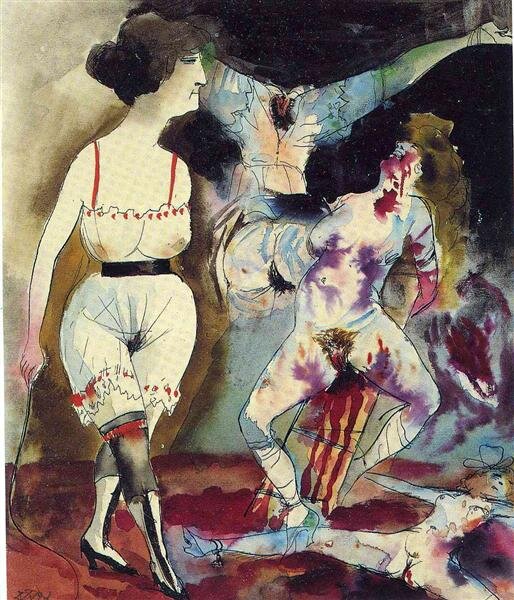

Eugene Delacroix, 1827, Romanticism, Louvre, Paris, France; Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA, US

Inspired by Lord Byron’s tale of Sardanapalus, the Assyrian king, Delacroix created this massive 12 by 16 foot masterpiece. As the tale goes, once, Sardanapalus learned he was facing military defeat, he ordered all his possessions destroyed, including his many concubines, servants and animals, before he committed suicide. This painting beautifully exemplifies the Romantic themes of bold colors, tragic imagery, and exotic decor. Delacroix used many literary sources as inspiration, including Shakespeare, Goethe and Byron, whom Delacroix largely admired. The Sardanapalus theme also inspired a cantata by Hector Berlioz and an opera by Franz Liszt.

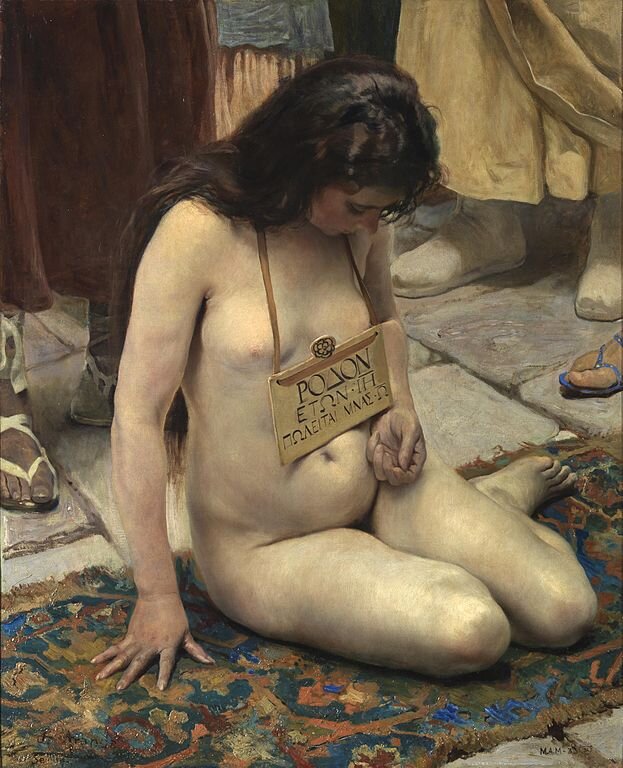

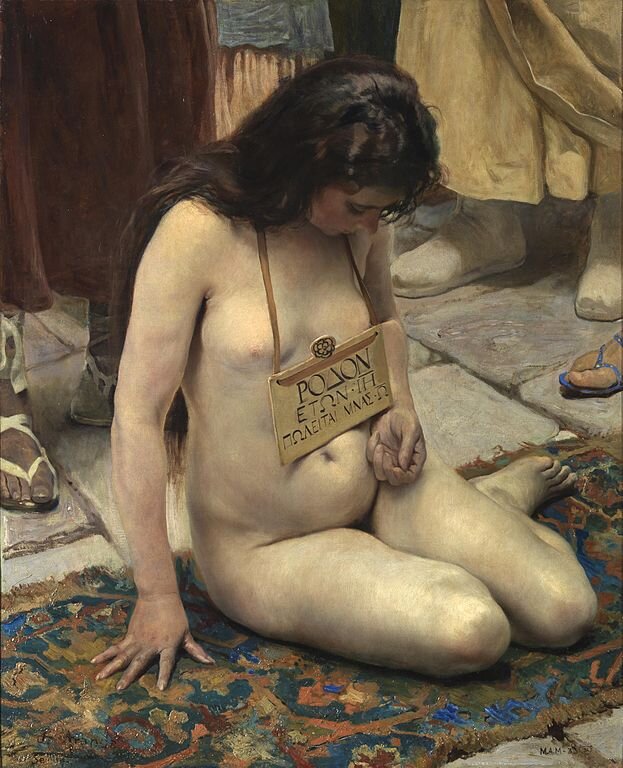

José Jiménez Aranda (1837–1903): Museo del Prado

A young, completely nude slave sits on a carpet. The sign hanging from her neck bears a Greek inscription (Rose, 18 years old, on sale for 800 coins) that offers her as merchandise at a market

Henri Rousseau, 1910, Naïve Art (Primitivism): Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York City, NY, US

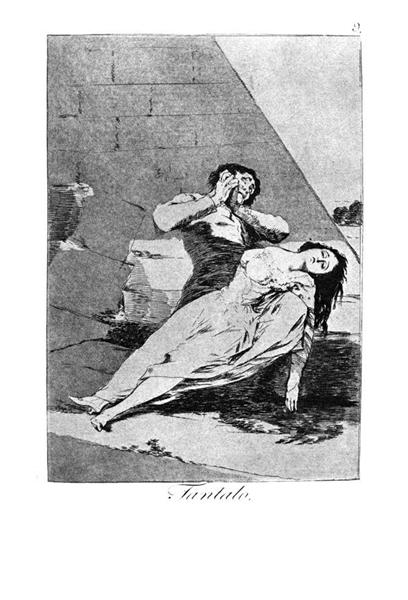

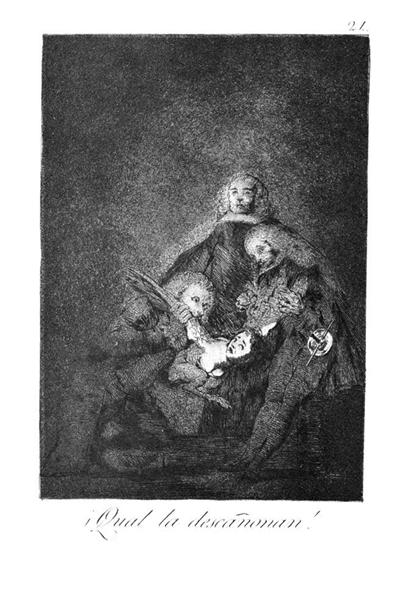

Goya, 1808-1812, Städel, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

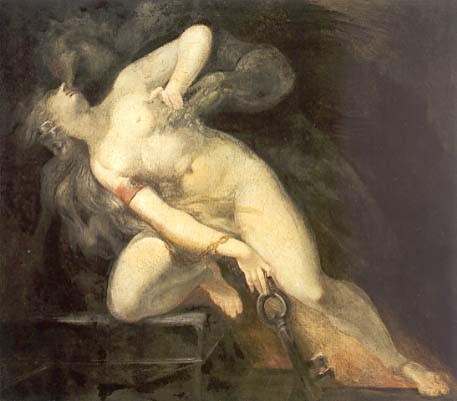

Henry Fuseli, 1780, Romanticism

Hiroshi Sugimoto, 1999, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Commissioned by Deutsche Bank AG in consultation with the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation for the Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin

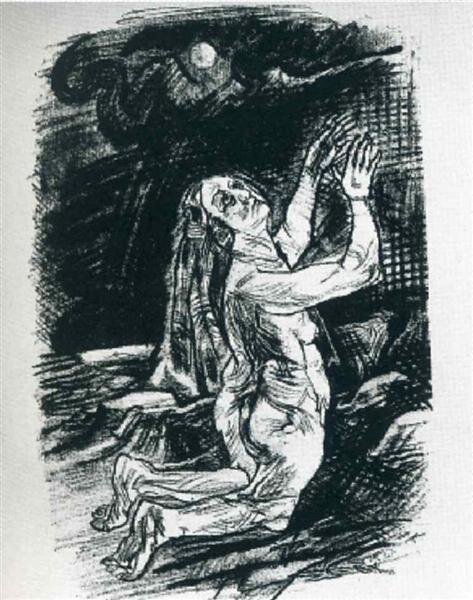

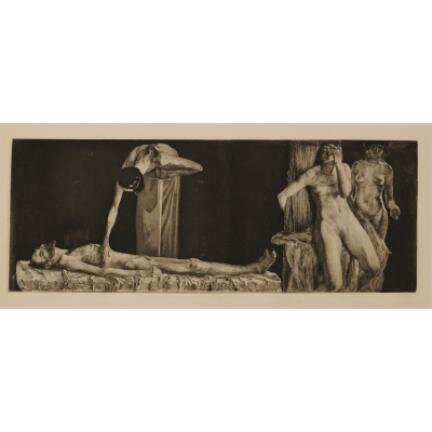

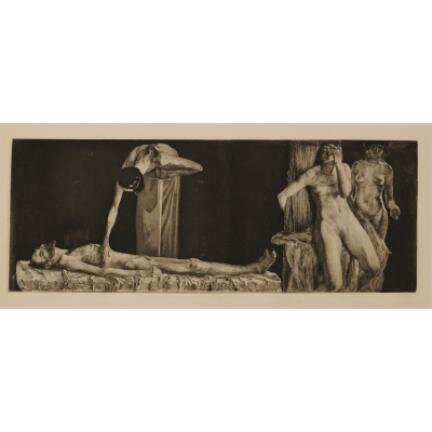

Kathe Kollwitz, 1900, Gift of Dr. Denis M. Shaw and Susan Evans, McMaster Museum of Art

Dimensions: Plate: 23.9 x 63.3 cm (9 3/8 x 24 15/16 in.) Support: 53.8 x 76 cm (21 3/16 x 29 15/16 in.)

Medium: Etching with aquatint and drypoint on paper

Eugene Delacroix, 1847 - 1849, Romanticism: National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Canada

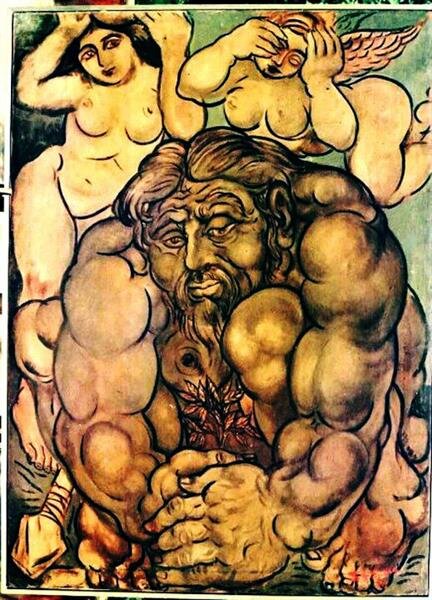

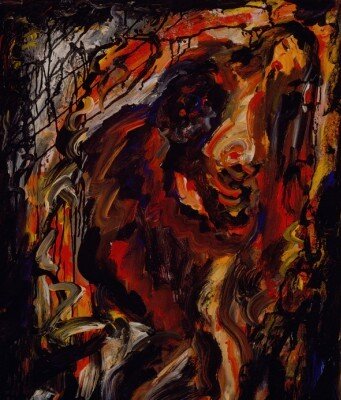

Nabil Kanso, 1985; Atlanta, United States, Neo-Expressionism

Pablo Picasso, 1905, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Thannhauser Collection, Bequest, Hilde Thannhauser, 1991

“Images of labor abound in late-19th- and early 20th-century French art. From Jean-François Millet’s sowers and Gustave Courbet’s stone breakers to Berthe Morisot’s wet nurses and Edgar Degas’s dancers and milliners, workers were often idealized and portrayed as simple, robust souls who, because of their identification with the earth, with sustenance, and with survival, symbolized a state of blessed innocence. Perhaps no artist depicted the plight of the underclasses with greater poignancy than Picasso, who focused almost exclusively on the disenfranchised during his Blue Period (1901–04), known for its melancholy palette of predominantly blue tones and its gloomy themes. Living in relative poverty as a young, unknown artist during his early years in Paris, Picasso no doubt empathized with the laborers and beggars around him and often portrayed them with great sensitivity and pathos. Woman Ironing, painted at the end of the Blue Period in a lighter but still bleak color scheme of whites and grays, is Picasso’s quintessential image of travail and fatigue. Although rooted in the social and economic reality of turn-of-the-century Paris, the artist’s expressionistic treatment of his subject—he endowed her with attenuated proportions and angular contours—reveals a distinct stylistic debt to the delicate, elongated forms of El Greco. Never simply a chronicler of empirical facts, Picasso here imbued his subject with a poetic, almost spiritual presence, making her a metaphor for the misfortunes of the working poor.

Picasso’s attention soon shifted from the creation of social and quasi-religious allegories to an investigation of space, volume, and perception, culminating in the invention of Cubism. His portrait Fernande with a Black Mantilla is a transitional work. Still somewhat expressionistic and romantic, with its subdued tonality and lively brushstrokes, the picture depicts his mistress Fernande Olivier wearing a mantilla, which perhaps symbolizes the artist’s Spanish origins. The iconic stylization of her face and its abbreviated features, however, foretell Picasso’s increasing interest in the abstract qualities and solidity of Iberian sculpture, which would profoundly influence his subsequent works. Though naturalistically delineated, the painting presages his imminent experiments with abstraction."

Nancy Spector

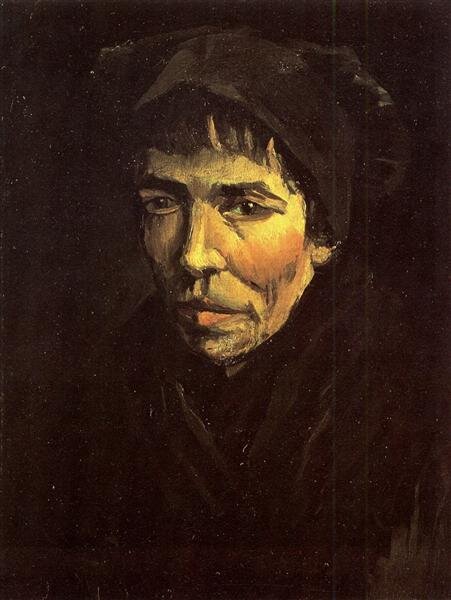

Vincent van Gogh, 1885; Nuenen, Netherlands: Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

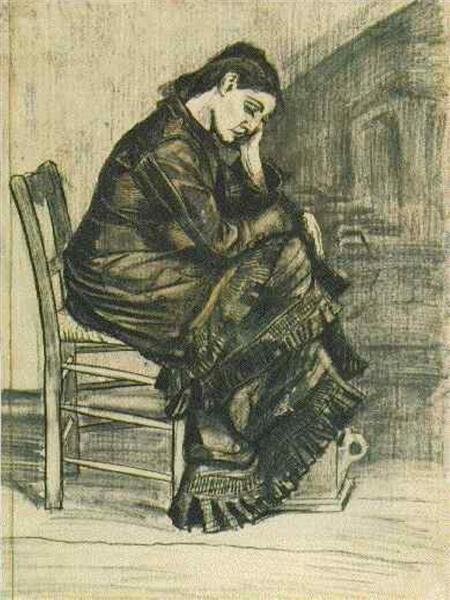

Vincent van Gogh, c.1883; The Hague, Netherlands: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Vincent van Gogh, 1882; The Hague, Netherlands: Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1871, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Thannhauser Collection, Gift, Justin K. Thannhauser, 1978

“The woman holding the parakeet is Lise Tréhot, an artist’s model and Renoir’s close companion of six years. Tréhot posed extensively for Renoir during the early years of his career, and her youthful features are recognizable in many canvases painted between 1867 and 1872. Renoir likely created this picture in 1871, soon after his return from the Franco-Prussian War and before Tréhot married an architect from a well-to-do family in April 1872, evidently never seeing Renoir again.

Using the feathery, textured brushwork that characterizes his work, even in this proto-Impressionist phase, Renoir depicts Tréhot as a bourgeois lady. Wearing a black taffeta dress with white cuffs and a red sash, she stands in an elegant interior adorned with ornately patterned carpeting and wallpaper, and exotic, verdant houseplants. Though the intimate scene suggests that Renoir has captured a young, upper-middle-class woman playing with her pet bird, the rich yet stifling interior restricts the model’s space, just like that of the parakeet when confined to its gilded cage. The analogy between the woman and the bird is further underscored by the model’s elaborate ruffled dress, appended by bright red plumage. Throughout art history, countless images of women with birds have foregrounded the intimacy and emotional bond between human and animal; in Woman with Parakeet, the bird may also play the role of confidant.

In this portrayal of the daily experience of a fashionable Parisian woman, a life relegated almost exclusively to indoor domestic spaces, the subtle tensions embedded in the painting frustrate the possibility of a purely pleasurable, innocent reading. Instead, Woman with Parakeet engages with the very contradictions that governed the lives of nineteenth-century bourgeois French women.”

Edvard Munch, 1895, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Estate of Karl Nierendorf, By purchase