The sage

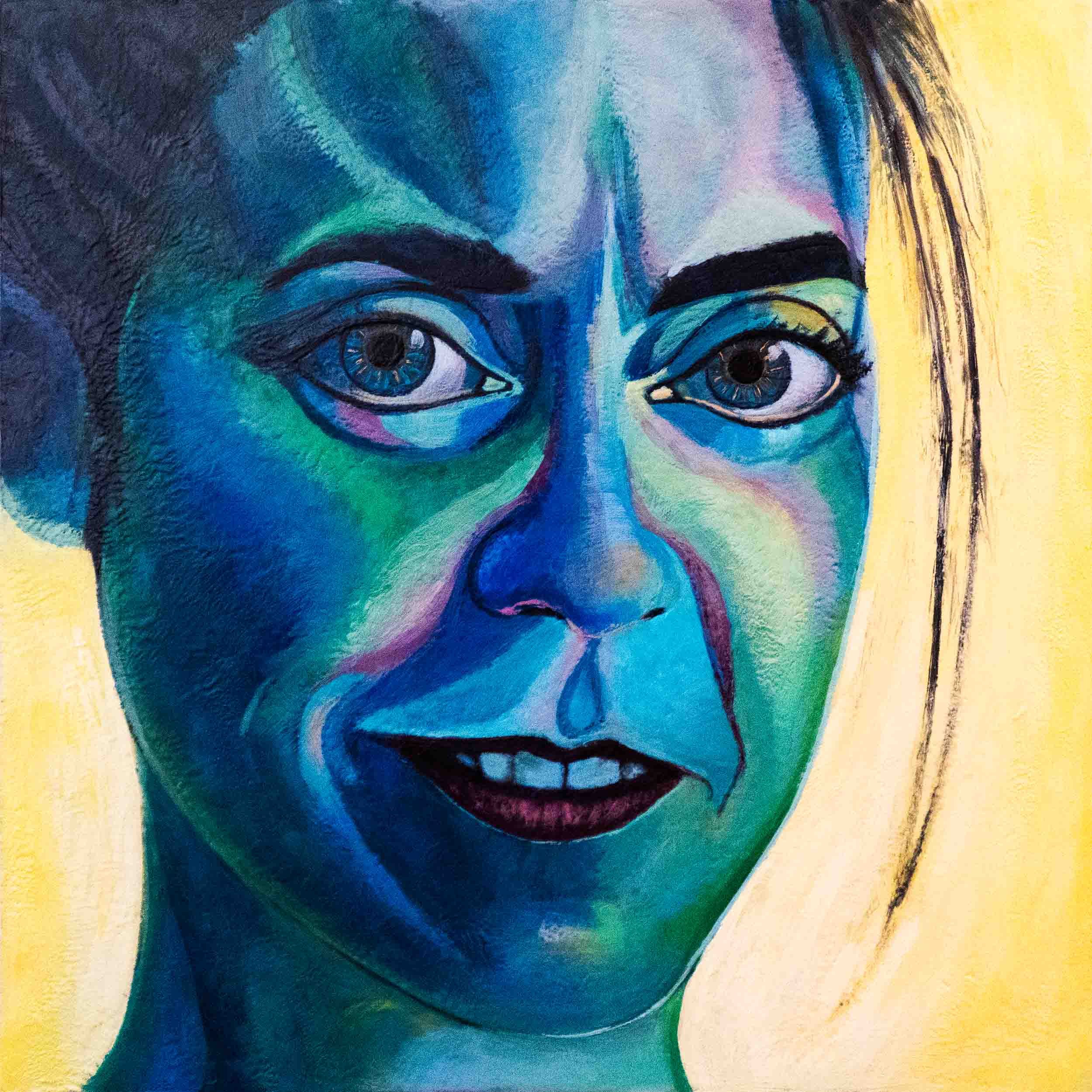

Impression of Edith Porada

A world-renowned expert on Mesopotamian seals, Edith Porada (1912, Austria - 1994, Honolulu) was a leading art historian and archeologist; and a professor of art history and archaeology at Columbia University.

Edith Porada was a pioneer in the study of Assyriology, Archaeology and Art History, particularly in her research on stamp and cylinder seals from the Ancient Near East and its vicinity including the Aegean and Iran.

“Whole provinces of art revealed themselves in these seal impressions.”

Blocks of clay served as a kind of lock for storage spaces and containers. On each one, a relief made by pressing a seal identified the owner.

A renowned scholar of the art of the ancient Near East, she received in 1977, the 12th annual Gold Medal Award of the Archaeological Institute of America for distinguished archaeological achievement. In awarding the medal, the Institute recorded: “its gratitude to the generous scholar to whom all of us, laymen, students and scholars, are indebted for making the world of archaeology more learned and more human.”

—Holly Pitman, Edith Porada 1912 -1994, American Journal of Archaeology

These astonishing miniature artworks were developed from 3500 to 2250 BCE in Mesopotamia.

Cylinder seals were created from semi-precious stones such as lapis lazuli, and were seen to possess magical powers. Prized as amulets and personal power symbols, people wore them as pendants or pinned to their garments and were often buried with them. Given that archaeologists have been able to match only a handful of surviving impressions to known seals, Sydney Babcock suggests that archaeologists have only discovered a fraction of the seals that existed or that others may have been made from wood and other perishable materials.

The Morgan Library & Museum in New York holds a world-renowned collection of more than 1400 cylinder seals.

“Seals run from the miserable to the spectacular.”

A seminal moment in Art History

Three stags with a plant showing individualized antlers becoming an abstract pattern, green-black serpentine, 2.5 centimetres, 3400-3000 BCE.

A composition carved into a cylinder of greenish black serpentine around 3400 to 3000 BCE, for example, depicts three stags walking one behind the other. At one level it is naturalistic: their legs are all in slightly different positions, and the gap between the front and back legs of each progressively widens, suggesting forward movement. The sculptor also varied the lengths of their antlers, but then stylized them to create, at the top, a continuous, gently undulating motif. Babcock sees this as a seminal moment in the history of art.

“This, I believe, is the first time that you have an artist who is consciously creating an abstract design out of natural elements.”

Cylinder seals proved to be practical for more than 3000 years.

People wrote on clay tablets and, as urban centers expanded, they authenticated official documents and letters by rolling their seals onto them. They did the same to establish ownership of containers filled with foodstuffs and other valuables. This also deterred pilfering, for a thief might easily replace a lid, but not one with the impression of the owner’s unique seal.

The same principle was at work when keeping track of debts and promises. If, say, someone owed the city a contribution of pots of honey, an administrator could place the appropriate tokens representing the debt into a hollow clay ball, pinch it shut and roll his seal and that of the debtor on the exterior. Later, as this and other debtors came through on their commitments, another administrator might deposit the goods in a storeroom, fasten the doors, slather clay over the locking mechanism and roll his seal over it.

— Lee Lawrence, Mesopotamia’s Art of the Seal

“The first person to really make people look at this as artwork, was the late Edith Porada, who in 1937, as a young archeologist from Vienna interested in early civilizations, spent six weeks at the Louvre in Paris studying seal impressions from Assyria produced from roughly the early 2000s BCE to 600 BCE.”

“For six weeks, I sat day by day on a rickety cane chair which had a big and rather painful hole in the middle. But of this, I was only aware at the end of the day at 6 p.m. Why? Because of the fascinating forms of the various styles. The whole provinces of art revealed themselves in these seal impressions, which at that time were completely unknown. People only knew them from drawings which were so miserable one had no idea of the style.”

For a very interesting article and video on cylinder seals with Sydney Babcock, visit:

https://www.aramcoworld.com/Articles/July-2021/Mesopotamia-s-Art-of-the-Seal

Edith Porada was a world-renowned expert on Mesopotamian seals.

Marvelling at the articulation of human figures in whose forms and proportions she saw more than acute observation; in 1993, she wrote to Sydney Babcock:

“I see the expression of man’s awareness of himself as the dominant element in nature.”

Edith Porada lead the way in charting the identification of distinct styles, articulating a fundamental split that occurred early on between designs with simple subjects that continued to be primarily engraved with a bow drill, and those in which careful work with a graver created rounded and even modeled forms depicting ritual and narrative scenes.

Edith Porada was the daughter of Dr. Alfred Rapoport Elder von Porada (1876-1962) and Käthe Anna Rapoport Edle von Porada (1891-1985); sister to Hilde Porada (1914-2012); and granddaughter of Laure Rapoport von Porada (1849-1904) and Arnold Rapoport Edlen von Porada (1840-1907).

She was also niece of my great grandmother, Bronislawa Allatini Rapoport von Porada (1869-1962); cousin to my grandmother, Rose Laure Allatini (1890-1980); and my first cousin twice removed.

Edith Porada graduated from the Realreform Gymnasium Luithlen in 1930 and received her Ph.D. from the University of Vienna in 1935 with a dissertation about glyptic art of the Old Akkadian period. Later she moved to Paris to study at the Louvre.

In 1938 Edith and her sister Hilda were living in Vienna. With worsening political climate, and the war drawing ever closer, they were advised by their father Alfred Porada that they should be ready to leave the country at a moment’s notice. When the call came, they had 30 minutes to leave the country. Edith emigrated to the United States where she worked at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on the seals of Ashurnasirpal II. Her sister Hilda emigrated to Honolulu.

Edith taught at Queens College and, beginning in 1958, at Columbia, attaining the rank of full professor in 1964. In 1969, she was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She was named Arthur Lehman Professor in 1974 and, upon retiring in 1984, held that title emeritus. In 1976 she was awarded the Gold Medal Award for Distinguished Archaeological Achievement from the Archaeological Institute of America. She was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1978.

Columbia University established an Edith Porada professorship of ancient Near Eastern art history and archaeology with a $1 million endowment in 1983. In 1989 Porada was awarded Honorary Degree of Doctor of Letters for Columbia for "profound connections between the human experience and the interpretation of the cylinder seals."

Columbia University art historian and archeologist. Porada was born to a wealthy family and educated privately in Vienna and at the family estate, Hagengut, near Mariazell, Austria. She graduated from the Realreform Gymnasium Luithlen in 1930.

Though initially interested in Minoan culture, she switched to near Eastern civilization because of the promise of discoveries yet to me made. Porada pursued her Ph.D. at the University of Vienna under the maverick art historian Josef Rudolf Thomas Strzygowski and, after his retirement, under the Ethnologist Robert Heine-Geldern (1885-1968) and the Sumerian scholar Viktor Christian (1885-1963). Her dissertation, accepted in 1935, was on glyptic art of the Old Akkadian period. At the advice of A. Leo Oppenheim (1904-1974), then at the Oriental Institute in Vienna, she moved to Paris to study the seals at the Louvre. In 1938 she emigrated to the United States where she worked at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on the seals of Assurnasirapal II, part of the collection of the Museum's first director, Luigi Palma di Cesnola. She was a staff member of the Museum, 1944-1945. She lectured widely around the United States. She became a U. S. citizen in 1944. The archaeologist Hetty Goldman (1881-1972) suggested Porada also study the cylinder seals at the Morgan Library. This resulted in her important publication, Mesopotamian Art in Cylinder Seals of the Pierpont Morgan Library, 1947. She was a lecturer at New York University in 1949. After a Guggenheim fellowship to Iran, she accepted a teaching position in the art department at Queens College, Brooklyn in 1950.

Despite no formal training in art history, she taught Western art courses in addition to archaeology. In 1958, Columbia University art history department chair Rudolf Wittkower, as part of his initiative to build a high-profile department, invited her to join the faculty. She developed a particular intellectual bond with the department's classicist, Evelyn B. Harrison. She conducted her seminars in the basement of the Morgan, surrounded by her seal casts, being named honorary curator of seals and tablets at the Morgan in 1956. She was promoted to full professor in 1963.

Between 1970 and 1973, she organized and directed Columbia's excavations on the Phlamoudhi plain in northeastern Cyprus. The excavation discovered a sanctuary of the Hellenistic period which helped prove the close commercial ties between Cyprus and the Greek islands in the late Bronze Age, ca. 1500 B.C. Porada was named Arthur Lehman professor in 1973. In 1977 she received the Gold Medal for outstanding service from the Archaeological Institute of America. Columbia University established an Edith Porada professorship of ancient Near Eastern art history and archeology in 1983 with a $1 million gift. Porada was named professor emerita of art history and archeology in 1984. In retirement she held regular graduate seminars at the Morgan and sat on the Board of Visitors to both the Sackler and Freer Galleries. She died at age 81. She lived much of her life with her father and friend, the socialite, Adeline Hathaway "Happy" Weekes Scully (d.1979). Porada's scholarship followed the tradition set by the Orientalists Anton Moortgat (1897-1977), whom she nevertheless disagreed with, and Henri Frankfort.

— Dictionary of Art Historians

Edith Porada (1912-1994), was a pioneer in applying her university studies of Assyriology, Archaeology and Art History to research on stamp and cylinder seals from the Ancient Near East and its vicinity including the Aegean and Iran. This book reprints some of Edith Porada's articles, copies of which may be difficult to obtain. They are sorted into three topics: work on collections, her methods, the transmission of concepts between the Aegean and Iran. Newly written articles contextualize them in present research. At the end of the book, Edith Porada's dissertation on Akkadian cylinder seals, which has never been published, is carefully reviewed. In 1933-34, Edith Porada worked on seal collections in Berlin such as the Hahn-Voss collection, the Sarre collection, and the Vorderasiatische Museum. Later she conducted research on the seal collections in Jerusalem (1938), the Pierpont Morgan Library (1946-48, 1976) and Columbia University (1964) in New York. Following a biography and bibliography the first section of the book deals with the collections that Edith Porada researched in Berlin. Reprints of her articles about the Jerusalem and US collections follow. The section covering methods begins with an introduction by Mirko Novak (Bern) and ends with memories about Edith Porada as a teacher by Dominique Collon (London). Founded on a detailed description of the design, Edith Porada aimed to localize and date a seal by way of technical considerations (way of engraving), style, general subject, composition and distinctive elements (garment, posture). She was reluctant to interpret the iconography on the basis of texts, assuming a split of the mythological tradition into a pictorial and a written form. An article by Joan Aruz introduces the section about the motifs and conventions that were shared from Iran to Cyprus. In her first reprinted article Edith Porada dealt with a faience cylinder from the Late Bronze Age. The seal was excavated in Mycenae. It depicts Mitannian glyptic design that corresponds to the style of cylinders found in Alala? and Ugarit. In further articles Edith Porada discussed cylinder seals from Hala Sultan Tekke in Cyprus, a Middle Assyrian cylinder found in Tyre, and another Middle Assyrian seal exhibiting Hittite elements. Analyzing a Theban seal in Cypriote style with Minoan elements, she used Egyptian motifs and their meaning for the interpretation of Cypriote scenes. Cylinder seals from Syria, Mesopotamia, east Iran and possibly Afghanistan found in the treasure of the Montu temple at Tod were understood as pointing to the trade routes that linked Egypt with Asia. She also wrote about a seal from Iran and another one depicting a storm god that reminded her of the golden Haslanu bowl found in Azerbeijan (Iran). A contribution by Holly Pittman about cylinder seals from southeastern Iran closes this part. The article concerning Edith Porada's dissertation depicts the seals, which she had analyzed, that are not shown in R. M. Boehmer's, Die Entwicklung der Glyptik wahrend der Akkad-Zeit (1965). Read together with Boehmer, this review of her first academic work provides an extensive presentation of Akkad seals. Her list of iconographic motifs is especially valuable. This book will be of didactic use for any introductory course on Ancient Near Eastern seals.

— Edith Porada - A Centenary Volume: Edith Porada Zum 100. Geburtstag: 268 Hardcover – 28 January 2015 German edition by Erika Bleibtreu (Editor), Hans Ulrich Steymans (Editor)

References

- https://www.aramcoworld.com/Articles/July-2021/Mesopotamia-s-Art-of-the-Seal

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cylinder_seal

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edith_Porada

- https://www.gf.org/fellows/edith-porada/

- https://arthistorians.info/poradae

- https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/author/?id=Edith+Porada

- https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/the-hasanlu-bowl/

- https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/aspects-of-elamite-art-and-archaeology/

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/506881

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/3045984

- https://www.spurlock.illinois.edu/collections/search-collection/details.php?a=1900.53.0145B

- https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1925-0110-27

- https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.2307/504736

Selected Bibliography:

"Edith Porada--Publications" Monsters and Demons in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds: Papers Presented in Honor of Edith Porada. Mainz on Rhine: P. von Zabern, 1987, pp. 6-11; and Dyson, C. H. and Wilkinson, C. K. Alt-Iran: die Kunst in vorislamischer Zeit. Baden-Baden: Holle, 1962, English, The Art of Ancient Iran; Pre-Islamic Cultures. New York: Crown Publishers, 1965; Mesopotamian Art in Cylinder Seals of the Pierpont Morgan Library. New York: Morgan Library, 1947.

Sources:

[obituaries:] "Edith Porada, 81, Dies; Columbia Art Historian." New York Times, March 26, 1994, p. 8; Pittman, Holly. "Edith Porada, 1912-1994." American Journal of Archaeology 99, no. 1 (January 1995): 143-146; Lawton, Thomas. "Dr. Edith Porada August 22, 1912-March 24, 1994." Artibus Asiae 54, no. 3/4 (1994): 376-377