The Messenger

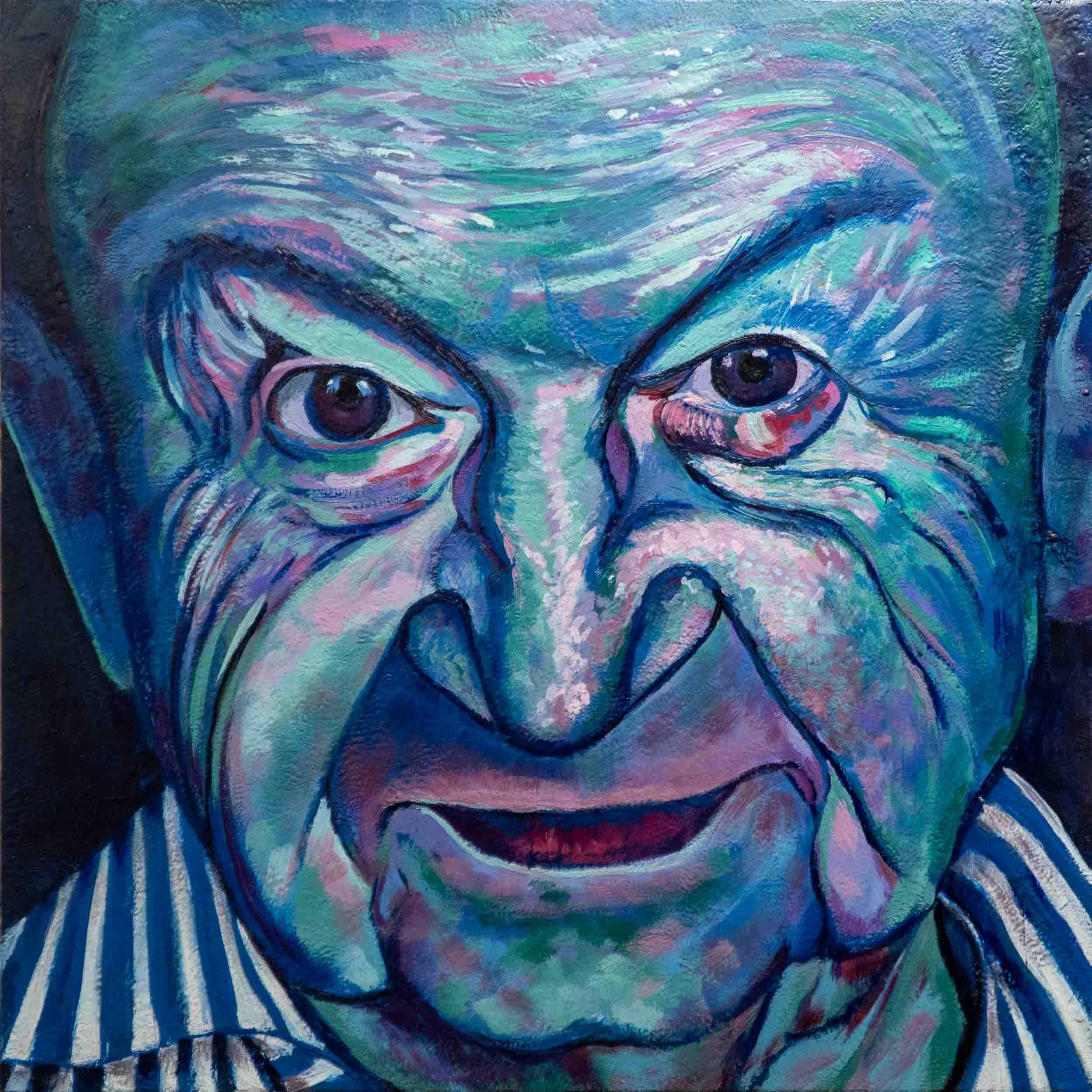

Impressions of Howard Chandler

“It’s vital that we learn from our history and be vigilant that it is never repeated by anyone and to anyone.”

Howard Chandler

Howard Chandler is a holocaust survivor and holocaust educator based in Toronto. Between 1942-1944, he was a prisoner in Starachowice Labour Camp and then sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau, then Buchenwald and was liberated from Theresienstadt in 1945. Since 2011, he has made annual journeys with Classrooms Without Borders to tell his story of resistance and survival during the Holocaust.

The colour scheme in this work was chosen for several reasons. Firstly, I find blues, greens and soft purples to be healing colours, which I hope softens some of the pain that I imagine must be associated with repeatedly sharing such a horrific story. To me, these colours also reflect the kindness and strength that radiates from this remarkable soul that we know as Howard Chandler. At the same time, my use of the specific blue: Prussian Blue— honoura and references the more sinister elements of his story that one can sense in the deep dark lines carved upon his face.

Prussian Blue has an interesting history. It was first discovered in 1704 in Berlin, by an artist seeking a different shade of red, of all things, and accidently formed by experimentation with the oxidation of iron. The pigment was then used to dye the uniforms of the German forces, becoming the signature tint of the Prussian army. By 1724 it had become a popular pigment among European painters of the time. Traces of the Prussian Blue pigment found on the walls and ceilings of the gas chambers in the concentration camps, result from the compound ferrocyanide, a byproduct of the Zyklon B gas used to exterminate the Jews. Elements of that same gas are traditionally used in making the Prussian blue pigment. Lastly, Prussian blue, also known as potassium ferric hexacyanoferrate, is used as a medication to treat thallium poisoning or radioactive caesium poisoning.

Hermes - The messenger

Hermes (/ˈhɜːrmiːz/; Greek: Ἑρμῆς) is the winged herald and messenger of the Olympian gods in Greek mythology.

He is also a divine trickster and the protector of travellers, flocks, merchants, thieves and orators.

Hermes was the only Olympian capable of crossing the border between the living and the dead, moving quickly and freely between the worlds of the mortal and the divine, aided by his winged sandals.

Hermes plays the role of the psychopomp or "soul guide"—a conductor of souls into the afterlife.

Howard Chandler was born Chaim Wajchendler, in Wierzbnik, Poland, on December 5, 1928. He lived with his father, Leibke Wajchendler, a shop keeper, his mother, Pearl Blima, and three siblings, Gitel, Hersh, and Shmuel.

Soon after the German invasion of Poland in 1939, the family wound up in the Starachowice ghetto, established by the occupying authorities in 1940. Upon the ghetto liquidation in October 1942, Howard was deported to the Starachowice-Julag II concentration camp with his father and older brother, Hersh. He never saw his mother and two other siblings again.

In 1944, the camp was liquidated, and Hersh was transferred to the Auschwitz II-Birkenau death camp. He later found out his father was transferred to the Stutthof concentration camp, where he died.

In January 1945, Howard was forced to march 100 miles to Breslau where he was put on an open freight train to the Buchenwald concentration camp. In Buchenwald, Howard reconnected with Hersh. As the allied forces drew near, the brothers were transferred to the Theresienstadt ghetto in Czechoslovakia, where they were liberated by the Soviet army on May 8, 1945.

In August 1945, with the help of the British Red Cross, both Howard and Hersh were taken to the UK, in Windermere. In 1947, Howard, as an underage orphan, had the opportunity to move to Canada.

He married a fellow Holocaust survivor, Elsa Biller, in November 1951. At the time of the interview, they had four children and four grandchildren. The interview was conducted in Toronto, Canada, on October 19, 1995. — USC Shoah Foundation

The middle child of 4 siblings; an older sister, with two younger brothers, Howard was born in Wierzbnik-Starachowice, Poland. During this time bullying and anti-semitism was rife but generally treated as a way of life.

When war broke out, Howard was 11 years old, in grade three. From this point on Jews were no longer allowed to attend school. He received an honorary high school diploma in 2011.

Later, he and his family were moved into a ghetto, living in crowded and unsanitary conditions with many other families. Disabled and aged friends and relatives were frequently killed before his eyes.

Although he was underage, Howard managed to get a work permit. This saved his life. One day in 1942 everyone was ordered to assemble in the centre square. Through a stroke of luck, Howard and his father and brother were selected for work, the rest of the family was taken away and sent to Treblinka where they were murdered. Many of his friends who also had work permits were not so lucky. They were sent to stand with the women and children, approximately 4500 people, who were subsequently loaded onto trains, jammed into freight cars, deported to Treblinka and murdered.

From 1942 - 1944 Howard worked as a forced labourer alongside his brother and father, living in barracks erected at the edge of town, a prisoner in Starachowice Labour Camp. The prisoners had no idea the Germans had erected extermination camps, although they did hear rumours, but it these were impossible to believe.

By 1944 the Germans were starting to retreat. They began to dismantle the factories and machines. This caused the inhabitants to realize that if they were no longer needed they would likely be killed. Some people tried to run away. Very few survived this. Many were shot and left, pleading for help, bleeding to death, hanging on the barbed wire surrounding the camp. These images haunt him to this day.

In July 1944, as the Russian front was drawing closer, Howard was loaded onto a freight train for a terrible journey without food or water. Arriving in Auschwitz, those who were still alive realized with horror that all the rumours that they had heard were actually true. However, to their surprise, they were put through a bath, given a tattoo (A-19831) and admitted to the camp.

A series of camps within camps, Auschwitz was a combination of concentration camp, forced-labour camp and extermination camp. Howard explains that when newcomers arrived, the Germans would select who they needed: bricklayers, metal workers, carpenters, dentists, engineers, architects, etc; the rest would be sent to the gas chambers and exterminated. When Howard arrived there was no selection because his group came as able-bodied ammunition workers, and he was lucky enough to be amongst them.

Howard remained in Auschwitz as a slave labourer until January 1945 when the camp was evacuated. By this time his father and brother had been sent away to an unknown location.

“Auschwitz was the most efficient killing machine. They could kill 10-20,000 people in a day.

But if you were lucky you also had a chance to survive. . .

It wasn’t the worst camp.

If they didn’t kill you, you had a fighting chance.”

In the winter of 1944, January, in freezing temperatures, the Nazis ordered the evacuation of the camp. In subsequent Death Marches, without warm clothes or food, prisoners were forced to march distances of approximately 100 miles. Great numbers of people lost their lives.

Howard ended up at Buchenwald, where to his joy he found his brother. A lot of Russian political prisoners were put in charge of the camp in Buchenwald, and as communists, they treated the prisoners better.

At the war was coming to a close, in April 1945, Howard and his brother decided to run away with the Russians. They were put on an open freight train, where they travelled for four weeks with only two days of rations, shuttled back and forth with no destination.

Finally in May 1945, they arrived in Czechoslovakia, where they were liberated by the Russians. Only 500 of them were left alive.

Howard and his brother were both in very bad shape but they managed to survive. They wanted to go back to their home in Weirzbnik, Poland, but were told by other survivors that the neighbours were shooting the Jews on sight. At the start of the war, many of the Jews had given their neighbours all their belongings, money and jewelry, etc, prior to deportation, for this reason the Polish inhabitants didn’t want to the Jews to return. Howard and his brother had nowhere to go.

Stateless, they decided they wanted to go to Palestine. The British delegation suggested that they go to Britain and from there they would be given a certificate for entry to Palestine. Howard and his brother were taken to England to recuperate.

Two years later, Howard applied to come to Canada where he was accepted as an orphan. Previously, Canada had not been allowing Jews to Canada but had relented to allowing orphans. Due to his young age, Howard qualified for this program. His brother did not. Howard came to Canada aiming to sponsor his brother. However, his brother met and married a girl in England and decided to remain there.

In 1947, when he arrived in Canada Howard learned of an uncle in Palestine and discovered that his mothers had two sisters in Canada.

In 1951, Howard married Elsa Biller, another holocaust survivor who had been liberated to Sweden after surviving Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. Together they have four children and four grandchildren.

Elsa & Howard Chandler

Elsa Chandler has worked with the Canadian Jewish Congress, Jewish Family & Child Service, Na’amat Canada, Reena, Canadian Jewish Holocaust Survivors and Baycrest.

Her most noticeable contribution has been to education both Jewish and Public. She worked as both a trustee including two terms as Chair of the North York Board of Education, for over 25 years. Elsa was also a member of the Metropolitan Toronto School Board and Chair of the Schools for developmentally challenged children. Elsa Chandler is also life member of Bialik having been there since their beginning.

““In Plaszów I was mostly hidden”, Elsa Biller, who was between eleven and twelve at the time, explained. Her use of the passive voice is deliberate. It was not she who was tasked with finding hiding places; it was her mother who pointed her daughter to them. Elsa spent her days on bunks, or generally “behind things.” The fear Elsa felt was slightly assuaged by her mother, who Elsa knew would take care of everything.”

REFERENCES

- https://www.marchofthelivingcanada.org/howard-chandler

- https://crestwood.on.ca/ohp/howard-chandler/

- https://www.jewishfoundationtoronto.com/book-of-life-stories/-00chandlerelse

- https://www.greekmythology.com/Olympians/Hermes/hermes.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hermes

- https://janeausten.co.uk/blogs/womens-regency-fashion-articles/prussian-blue?currency=cad

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zyklon_B

- https://www.webexhibits.org/pigments/indiv/overview/prussblue.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prussian_blue_(medical_use)