introduction

Looking at women in a new light

The way women are depicted in the arts colours how we see and treat women today.

In Western culture, women are largely portrayed either as sexy, dangerous creatures, or as victims. Implicit in this is the message that women are not to be trusted and that they deserve what they get. Author Erika Bornay posits that in ancient times, since the act of lovemaking is so all-consuming, people were unlikely to focus on other matters, such as conquering neighbouring tribes and amassing territories. It was therefore necessary to invent reasons to desist: hence the idea of the woman as a conduit for evil.

Be that as it may, the astounding volume of artworks dedicated to rape, voyeurism and dangerous women, speaks of a deep-rooted fear and hatred of women which, consciously or unconsciously, serves to justify the resulting violence against them. And this is a problem facing us today.

Is this what we want for future generations?

If not, we need to re-frame thousands of beautiful artworks by inviting viewers to consider the implicit messages in artistic masterpieces and how these reflect our attitudes towards women today.

In her book Lilith’s Daughters/Las Hijas de Lilith, Erika Bornay traces the roots of misogyny and attributes the surge of femme fatale depictions in 19th and early 20th century art to male anxiety and fear triggered by the rise of women in the workforce and the resulting shift in gender-based roles. Bram Dijkstra, in his book Evil sisters: the threat of female sexuality and the cult of manhood, explores how the female came to be portrayed as a dangerous primal force whose unbridled sexuality threatens to destroy the social order and undermine white male supremacy. Dijkstra goes on to link this with misogyny, racism and the politics of genocide. Clearly this topic has been explored in considerable depth by writers such as Bornay, Dijkstra and others, so why am I jumping into the conversation? What do I have to add here?

As a female artist with lived-experience of the subject, and as one who shares the complexities of dual identity (assimilating from an ancient culture into a series of dominant cultures through inter-generational immigration) as well as one who experiences “double colonization” (the simultaneous oppression of both colonialism and patriarchy) I believe that in order to progress, we need to look at women of all cultures in a new light. We need to move from envisioning women as dangerous yet simultaneously powerless victims to recognizing them as self-individuated heroines. We need to change the narrative to engender female empowerment. And we need to move this dialogue from the realm of academia into museums and galleries with the will to embrace dialogue with visitors, and cultivate change. I offer this through my encaustic paintings, installations and workshops.

I have been observing how museums and galleries in Europe and North America are starting to address the role of women in the art world. Many museums are doing exceptional work focusing on women as artists, patrons and subjects, but to date very few are addressing how so many artworks, reflecting toxic core beliefs about women, impact women’s lives today. Of all the exhibitions I have seen to date, Curator Joan Molina’s exhibition El Espejo Perdido, comes the closest to connecting the power of the image to serious issues facing us today. This exhibition traces how images of Jews in medieval art fostered antisemitism but it is equally powerful when viewed from a feminist perspective, as the Jew is often portrayed as an old, ugly, traitorous and/or blind woman.

I have imagined myself in a gallery with a young girl, who — after seeing a sculpture of a woman weeping or being attacked — turns to me and asks: “Is that going to happen to me when I grow up?” And I imagine responding: “It happened to me, but I won’t let it happen to you.”

Recently, I was in the Prado Museum in Madrid, contemplating a powerful sculpture entitled Grief, by Llimona I Bruguera, which depicts a beautiful naked woman weeping into her arms. Glancing up, I noticed a young girl also looking at the work, with a very concerned look on her face. Her mother also seeing this, immediately steered her away to look at a landscape painting. I was fascinated. The girl had responded to the sculpture almost as I had imagined one might. In the moments that followed an opportunity was missed. Perhaps intentionally. Perhaps unconsciously. Was her mother seeking to protect her daughter? Or had they already experienced enough of life’s pain and suffering? Either way, discussion about real life issues was avoided for now. But, art is extremely powerful. Whatever her mother’s motivations might have been, the girl recognized what she was seeing. And neither she nor I wanted this in her future.

Grief, Josep Llimona i Bruguera, 1907, Marble, Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain

I aim to inspire museums and art galleries to embrace discussion about the power of imagery, our tendency to imitate what we see, and how we can create positive change in the world.

I believe it is very important that we find a new way of reflecting on and representing women in the arts because it impacts how we see and relate to women in our world today.

As we consider issues such as the portrayal of women in art, our roles in society, and the ever-increasing rates of physical and sexual violence against women, we can also re-imagine the role of galleries and museums. I believe museums and galleries have an opportunity to become gathering places for people to see art, to consider how it relates to their lives, and to engage in discussions on how we address social issues as a community.

A pressing issue today is rape. Rape is used as a weapon of war, as a means to demoralize women and control populations, and as a form of genocide. The only way this will end is if we can shift men’s attitudes towards women.

Many men romanticize the idea of rape, as is evidenced by any museum visit. Recently when I shared my story with a fellow artist, his response was: “Is it true that some women fantasize about rape?” The sheer naivety and insensitivity of this response illuminates his privilege. Only one who has never experienced the sense of powerlessness, helplessness, fear, dread, pain, shame, rage, blame and self-loathing that accompanies a rape would luxuriate in such fantasies. Today, women and girls struggle against the assumption that they are “asking for it” when they are raped. We are expected to modify our behaviour, change the way we dress and do whatever we can to avoid being raped. Men and boys are rarely taught not to rape. “No” is still pushed and tested. Erectile enhancement drugs are readily available while women must fight for the right to choose whether or not to carry unwanted pregnancies to term.

Some artists reflect their experiences by exposing their bodies, testing the limits of violence with viewers; or share their horror through lurid depictions in blood; or most eloquently as Kara Walker does — through powerful silhouette cut-outs illustrating violence inflicted upon America’s black population, particularly women, during the American Civil War.

Me, after extensive research and study, prowling the art world, reading and talking to other survivors: I celebrate women’s inner-strength and determination, the fire that keeps us going despite the horrors many of us have endured. Through encaustic paintings, installations, videos and workshops, I celebrate the power and strength of women of all ages, cultures and walks of life; our triumphs over adversity, and our indomitable resilience.

Nadia Murad is one such woman. Yazidi Human Rights Activist, Nadia Murad was kidnapped by ISIS, imprisoned, raped and tortured repeatedly. Upon her escape she founded Nadia’s Initiative, an organization dedicated to helping victims heal; and to ending the use of sexual violence as a weapon of war and armed conflict. As Nadia said: “ISIS did not come down from the sky. They found the opportunity to grow, and the world allowed them to grow.”

I named this painting Echoes of the Sabine Women to remind viewers of the ancient story of the Rape of the Sabine Women — a frequent subject for sculptors and painters, particularly during the Renaissance and post-Renaissance eras but continuing up to the present day.

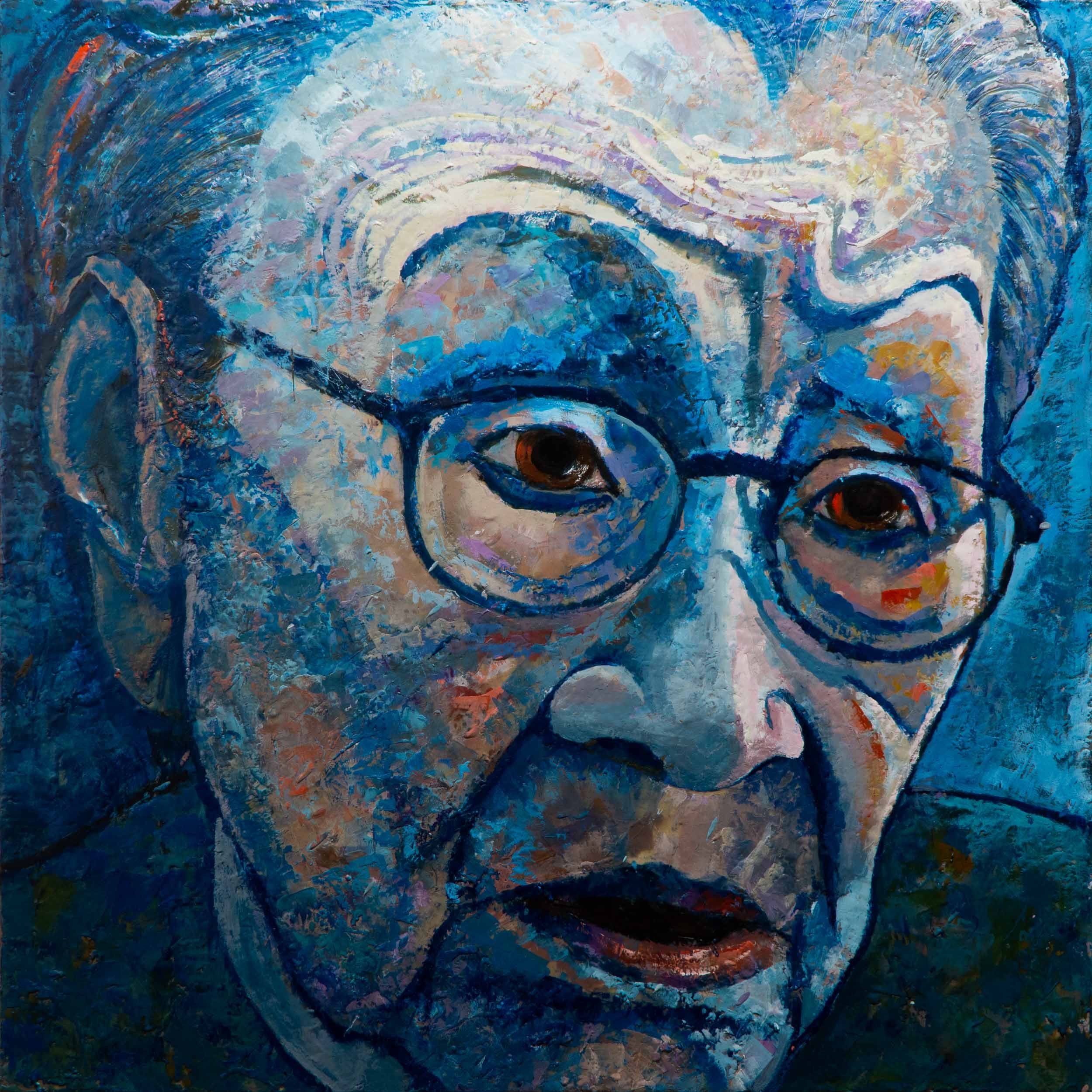

In this work and the entire series, Eyeing Medusa the titles of my works referenced well known myths and legends, so I felt no need to illustrate the stories. Reacting against toxic depictions of women — which carve pathways in the mind supporting ideas that toxic behaviour is fundamentally acceptable — I focus upon the face of individual, so viewers may gaze into her eyes and feel her strength.

I explore the myths of legendary heroines (and heroes) to contextualize recurring patterns in history, understand the psychological motivations of each archetype and connect emotionally with their struggles, strength and resilience. This inspires my artistic practice and fuels my fire to address urgent contemporary social issues.

Human rights activist, Kim Bok-dong, forced to work as a “Comfort Woman” for eight years during WWII, campaigned against sexual slavery and rape as a weapon of war, and set up the Butterfly Fund to support fellow victims of sexual slavery, bringing together survivors from around the world.

I saw her as Persephone, abducted by Hades to be his wife in the Underworld. Persephone speaks to me about the evolution of women: how we learn and find our wild wise selves and reclaim our power. No longer victims, we become a voice for change.

Malala Yousafzai was shot in the head for defying the Taliban when she spoke out publicly on behalf of women’s rights to receive an education. Malala survived and established Malala Fund a charity dedicated to giving every girl an opportunity to learn.

“There is overwhelming evidence that sexual assault perpetrated by Taliban officials is widespread and systemic, and that it occurs with total impunity.”

I saw Malala as Medusa’s daughter, fighting for the rights her mother was denied.

Because the story of Medusa echoes the experiences of so many women, I created my installation, Eyeing Medusa, in her name, to raise awareness and inspire people to look at women in a new light.

Originally Medusa was a very beautiful woman, one of the sacred priestess in the temple of Athena. Medusa was raped by Poseidon, god of the sea; blamed by Athena for being raped in her temple; transformed into a raging monster; forbidden to pursue her spiritual path; banished from her homeland and subsequently beheaded. Pregnant by Poseidon at the time of her death, Medusa’s assassination released her two unborn children Chrysaor and Pegasus (the winged horse) from her gaping neck. As Perseus flew back to Athena, the blood dipping from her severed head populated the land below with snakes. Placed on Athena’s shield, her terrifying image turned all who looked upon it to stone.

Medusa is the archetypal wronged woman of Greek mythology, a symbol of female rage, the personification of female fury. What made Medusa so angry? Because she was not consulted. Her rights were denied. Because she was wrenched from her spiritual path, raped, blamed and destroyed. I look at the history of many colonized countries, in which, sadly, the treatment of Indigenous people echoes the story of Medusa.

Like Medusa, Indigenous people were following their own spiritual ways when settlers arrived to colonize the continent. They were betrayed, raped, banished to remote reservations and murdered. They have been stereotyped, punished and ridiculed. Indigenous people have survived relocation, and residential schools — where they were sexually assaulted and banned from speaking their native languages. Today they suffer from ill health, poor living conditions, above average rates of incarceration and death by suicide. They wrestle with systemic racism, low self esteem, substance abuse, violence and mental health issues such as life-long PTSD and fetal alcohol syndrome. And still they rise up to teach the world!

This work, Medusa’s Rage, honours Autumn Peltier, an Indigenous environmental activist, who has been drawing global attention to the lack of safe drinking water in numerous Indigenous communities across Canada.

I paint empowered individuals who have campaigned for peace and human rights, challenged toxic ideas about women, and raised awareness of rape as a weapon of war, colonization and oppression, and the destruction of our planet.

Sexual violence continues to be used as a weapon of war all over the world, including Afghanistan, Israel, Haiti, Ethiopia, the Congo, Uganda and Ukraine.

My sincerest hope is that if we can reflect on and change how we see women in art we can change how women are treated in the future and perhaps find peace.