Me too, Medusa

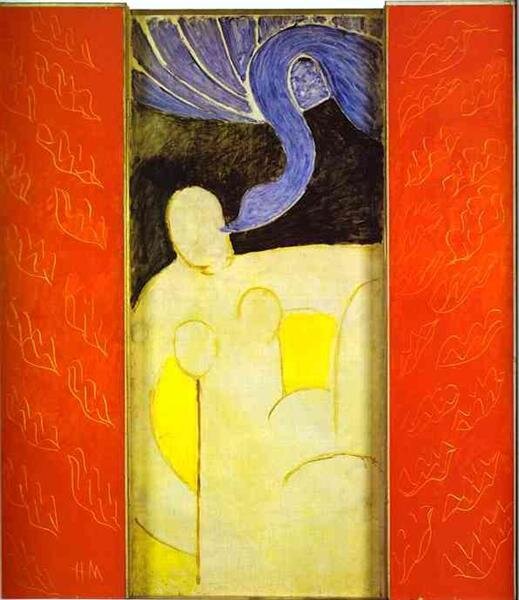

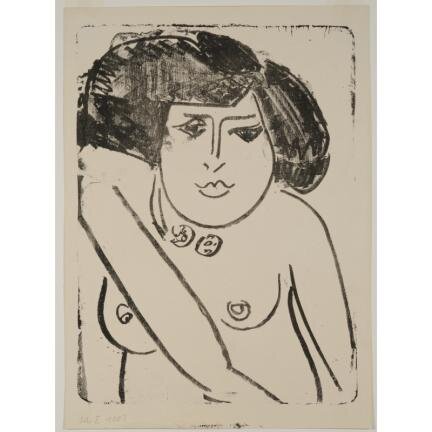

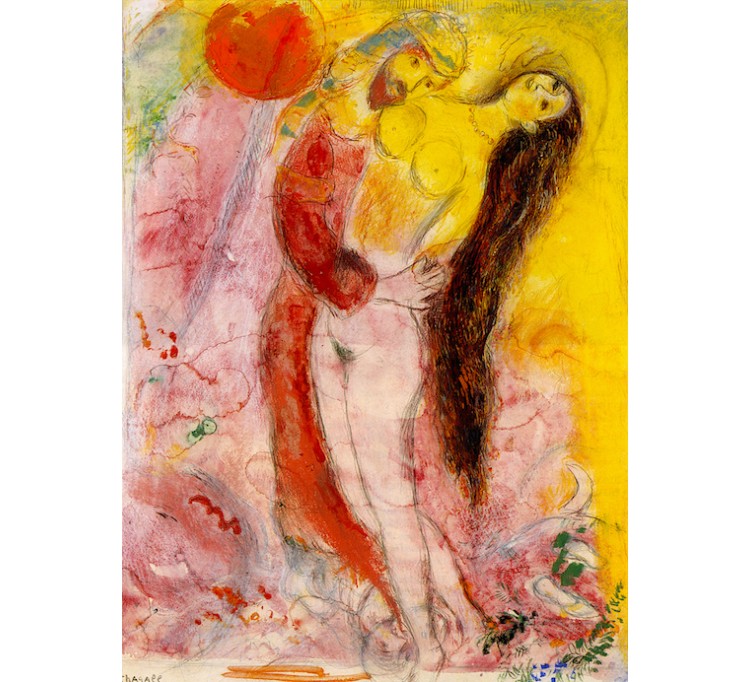

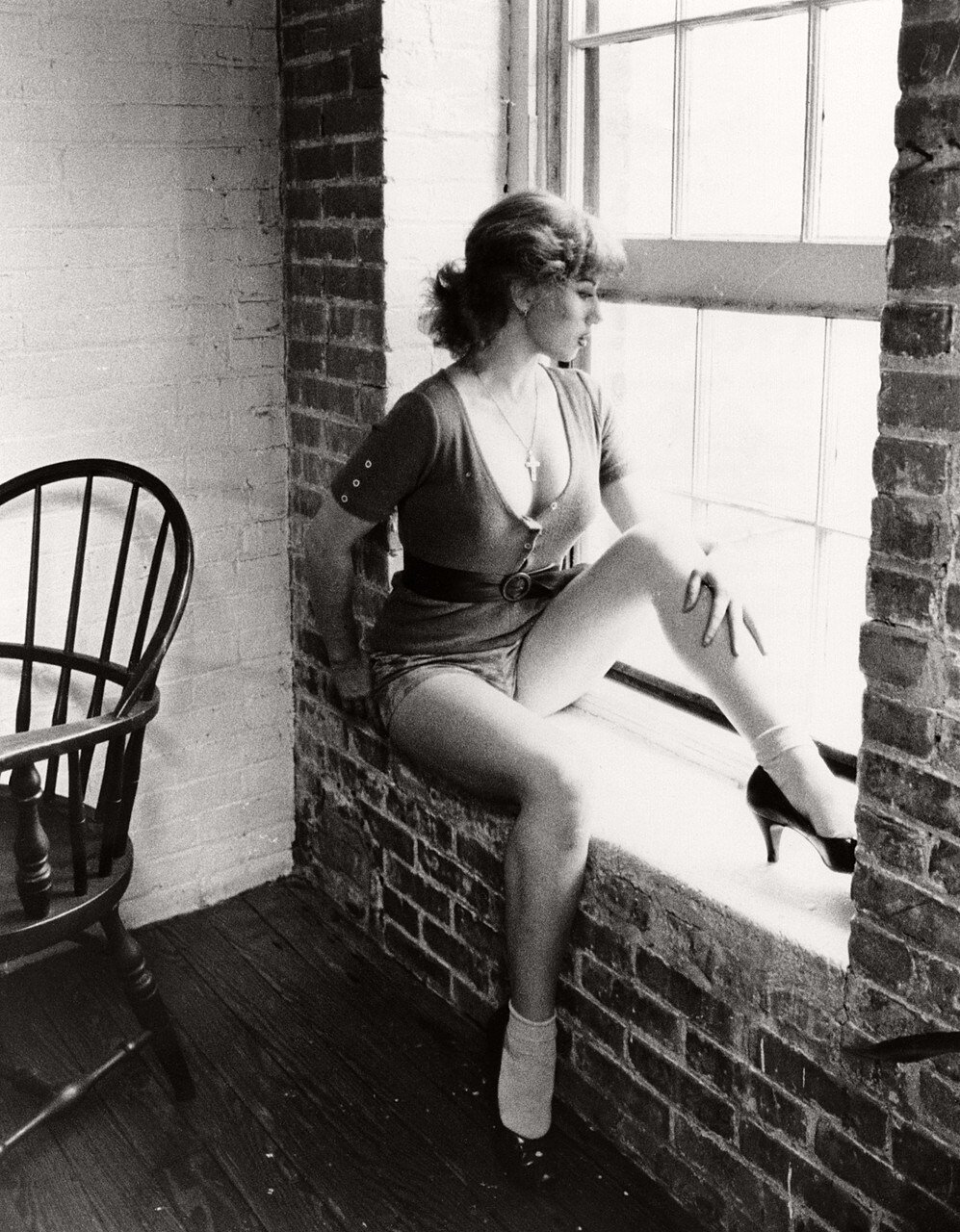

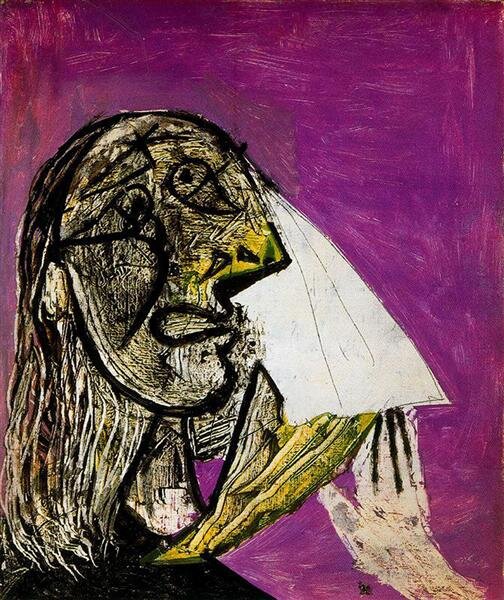

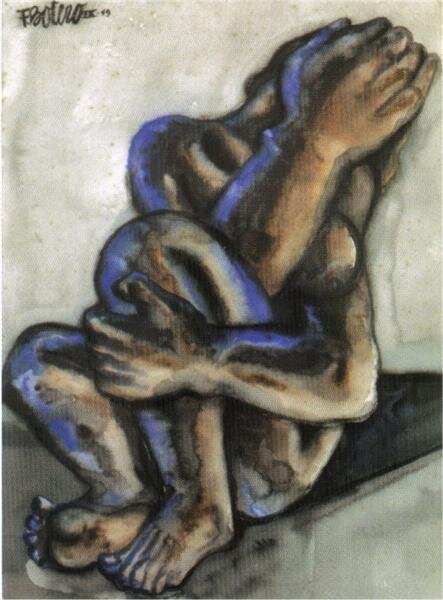

impression of Tarana Burke

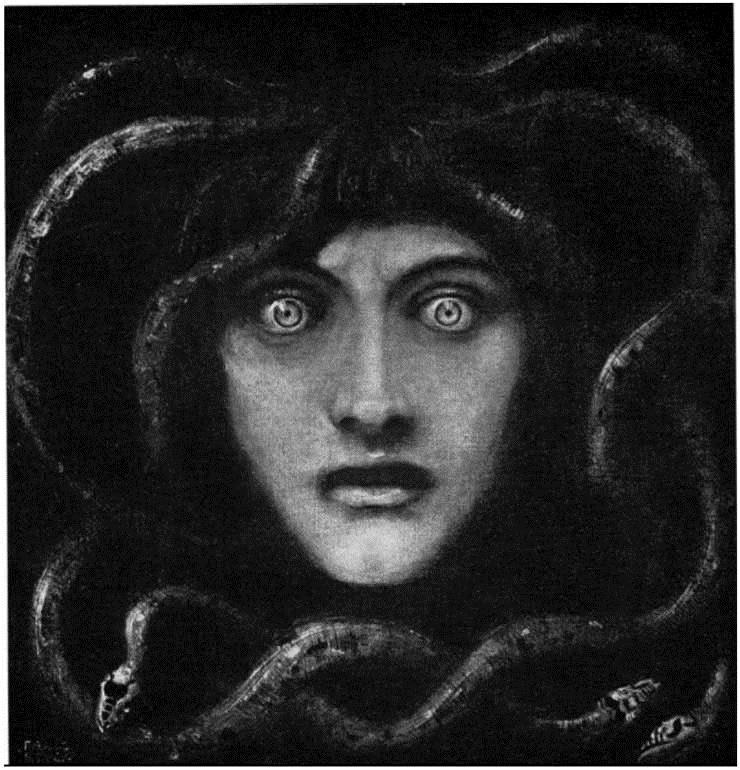

Medusa was raped, blamed, murdered and vilified.

Tarana Burke, an African-American civil rights activist from The Bronx, New York, started the #MeToo movement: a global phenomenon that raised awareness about sexual harassment, abuse, and assault in society.

“I know exactly how you feel, that happened to me too.”

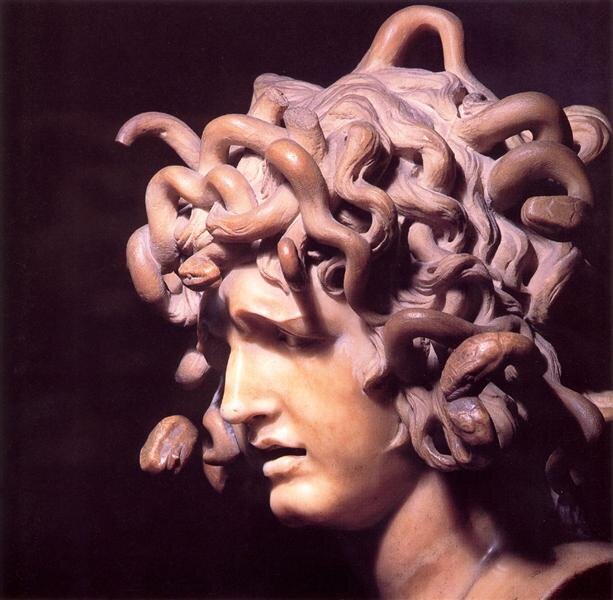

MEDUSA

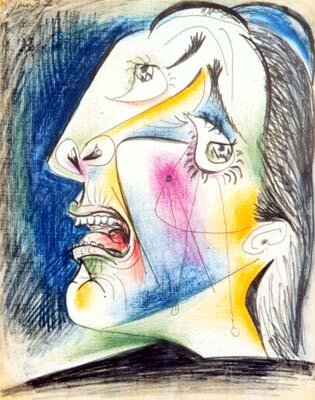

The story of Medusa is the classic story of a rape victim who is defiled, punished, blamed and destroyed for her misfortune.

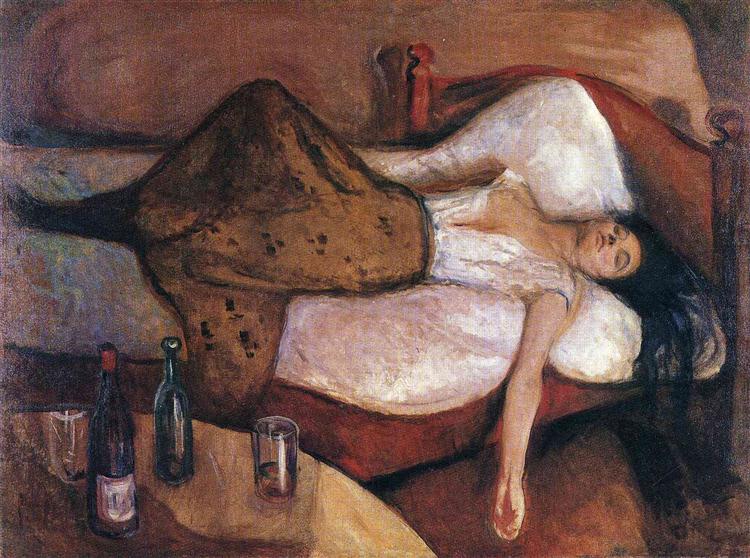

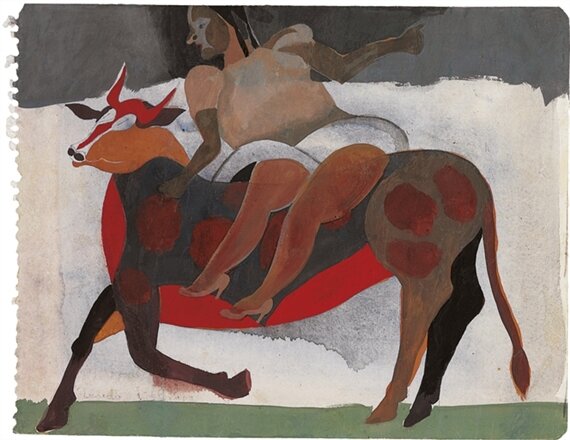

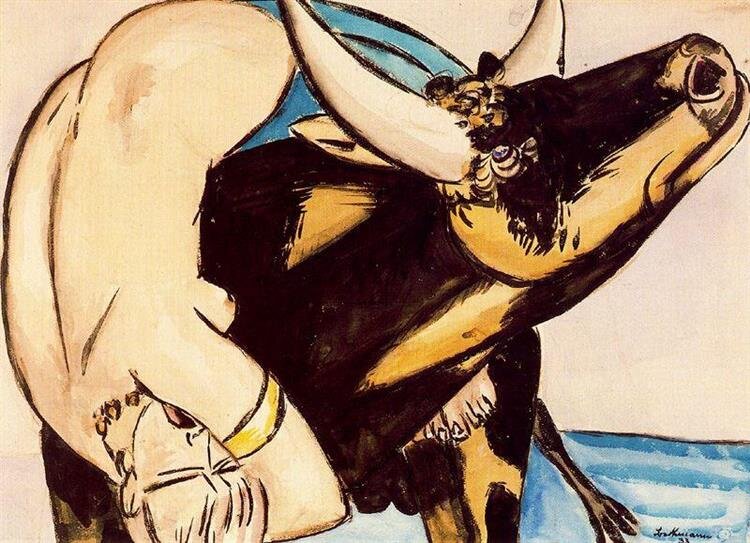

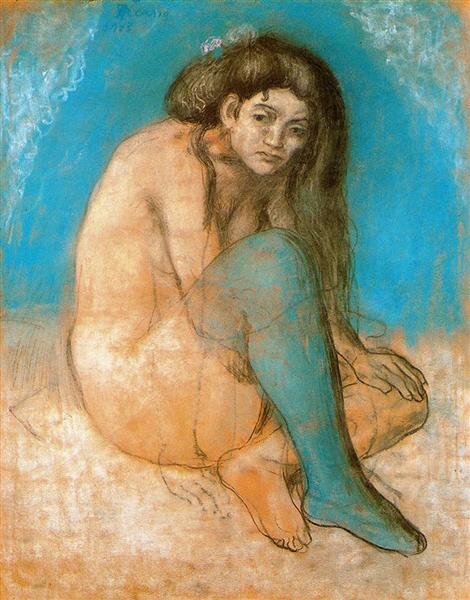

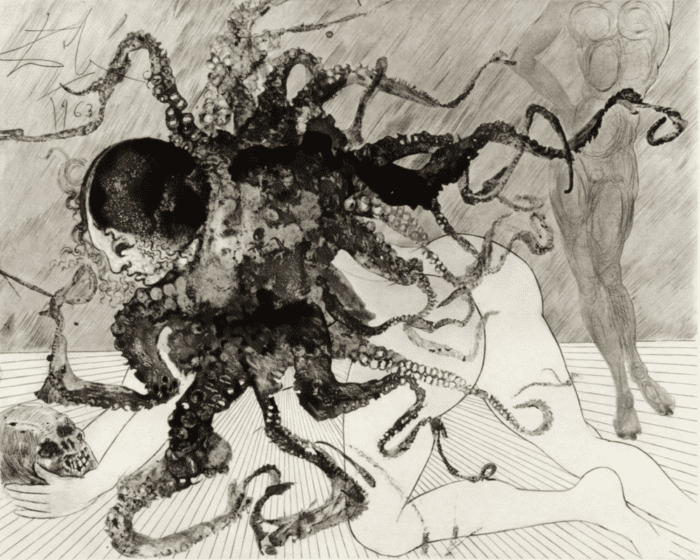

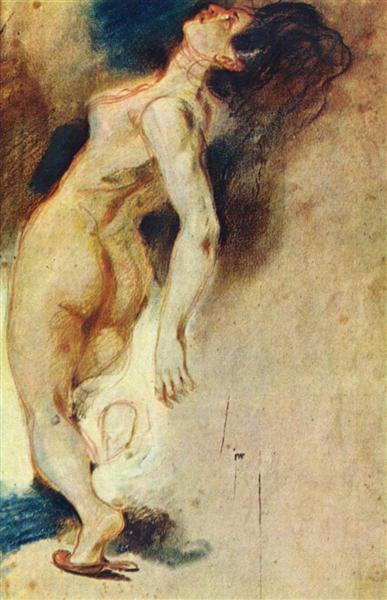

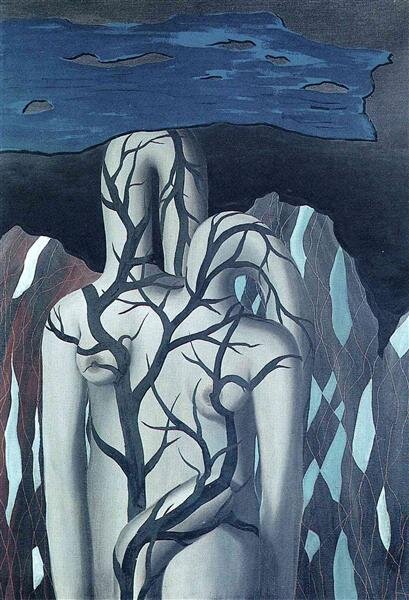

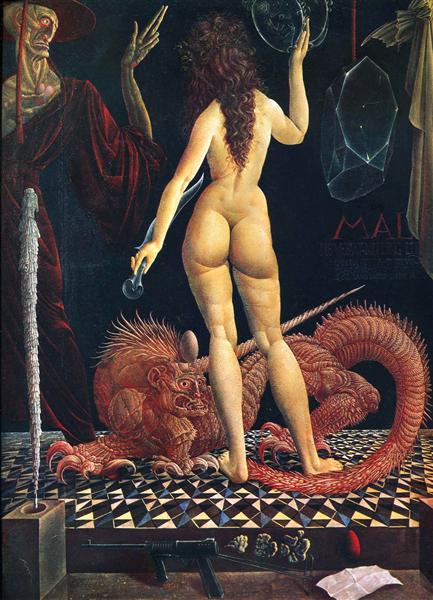

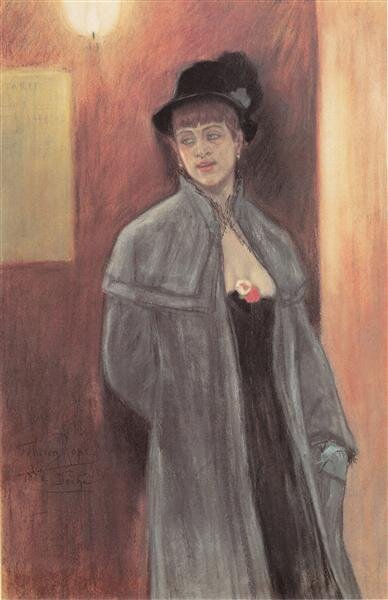

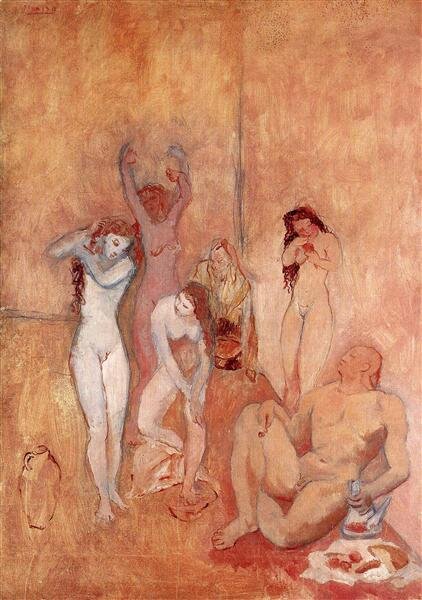

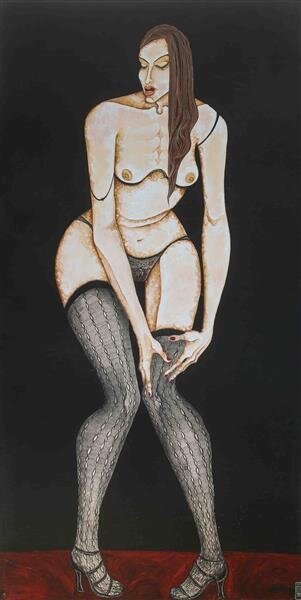

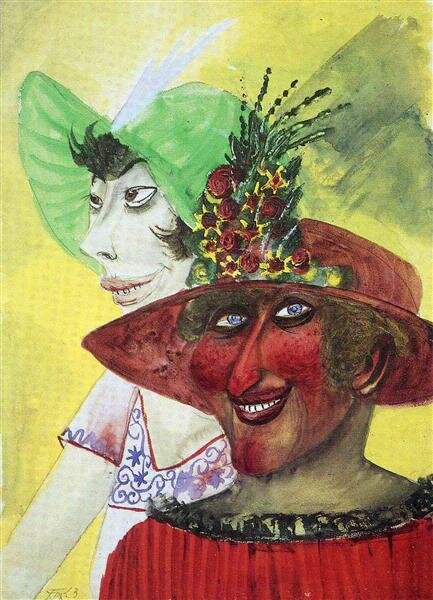

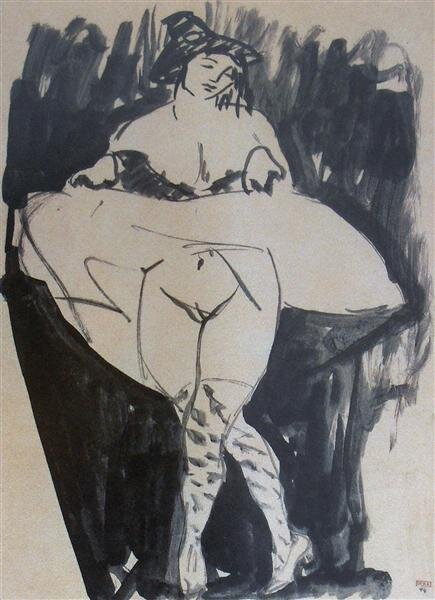

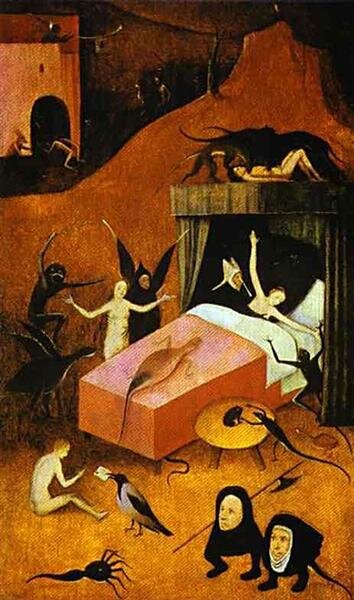

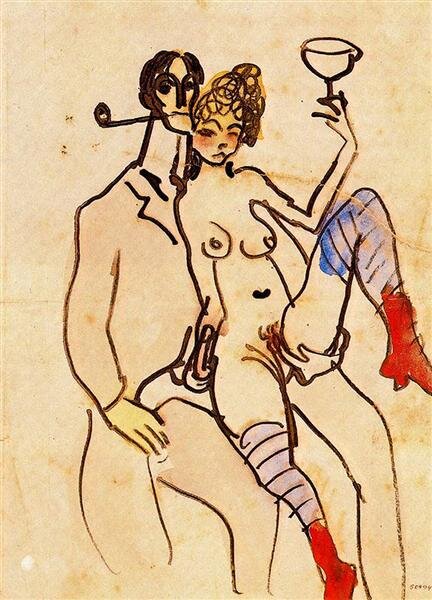

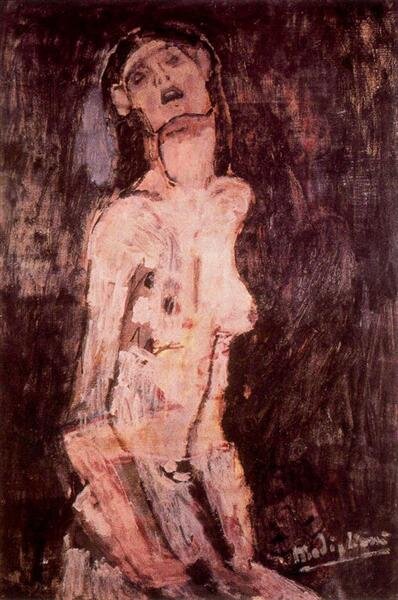

Medusa has been depicted as either a monster or a beautiful woman: raped (or sexually active); then blamed for being raped (or for engaging in sex); then transformed into a raging monster and subsequently beheaded. Medusa seems to materialize whenever male authority feels threatened by female agency.

“Medusa remains the symbol of the quintessential nasty woman that must be vanquished in order to restore the balance of power.”

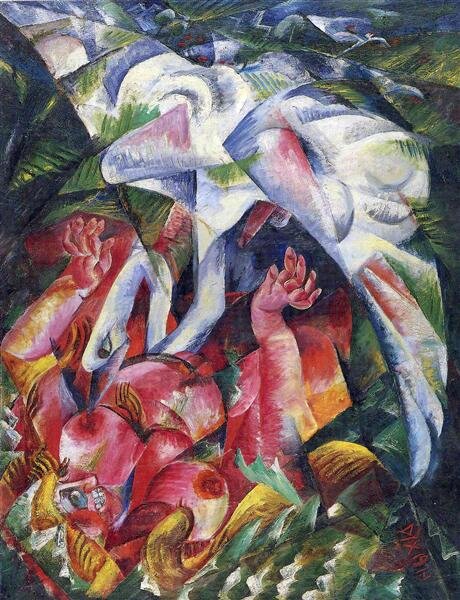

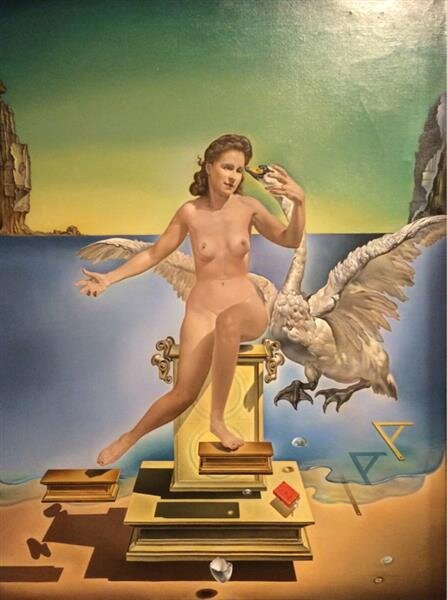

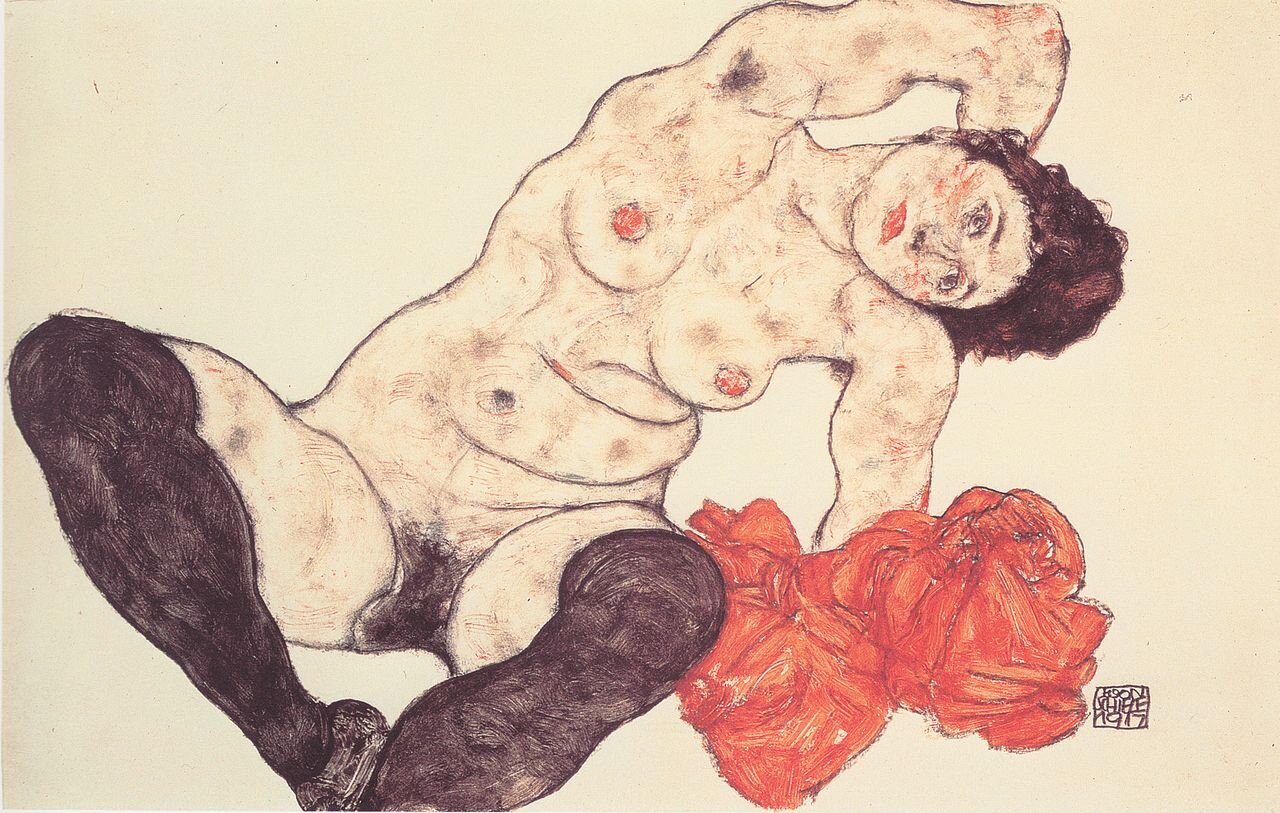

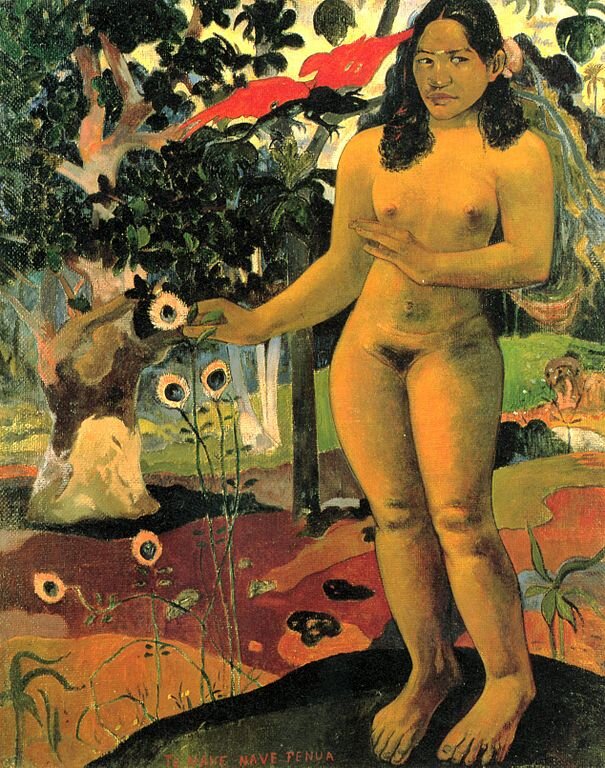

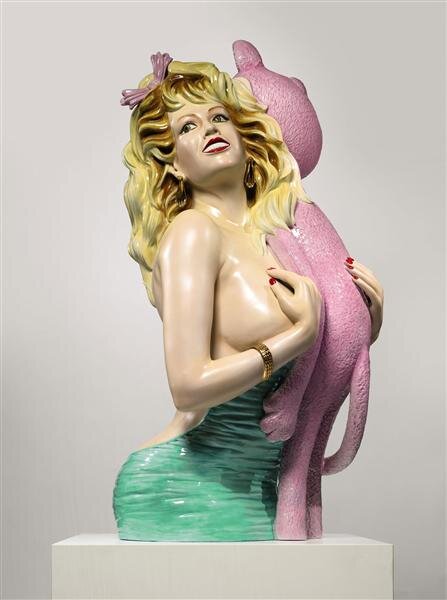

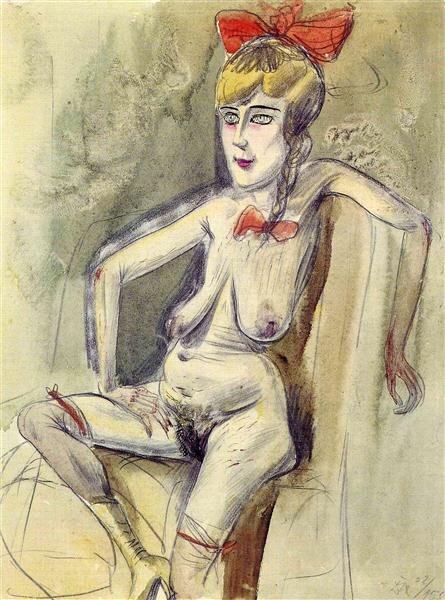

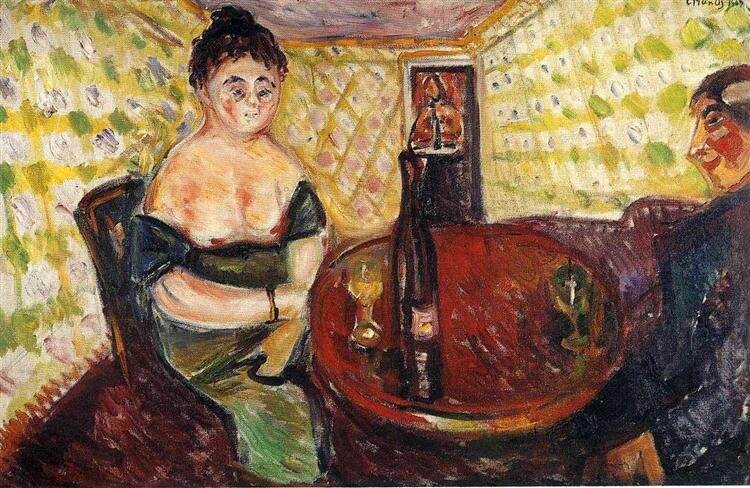

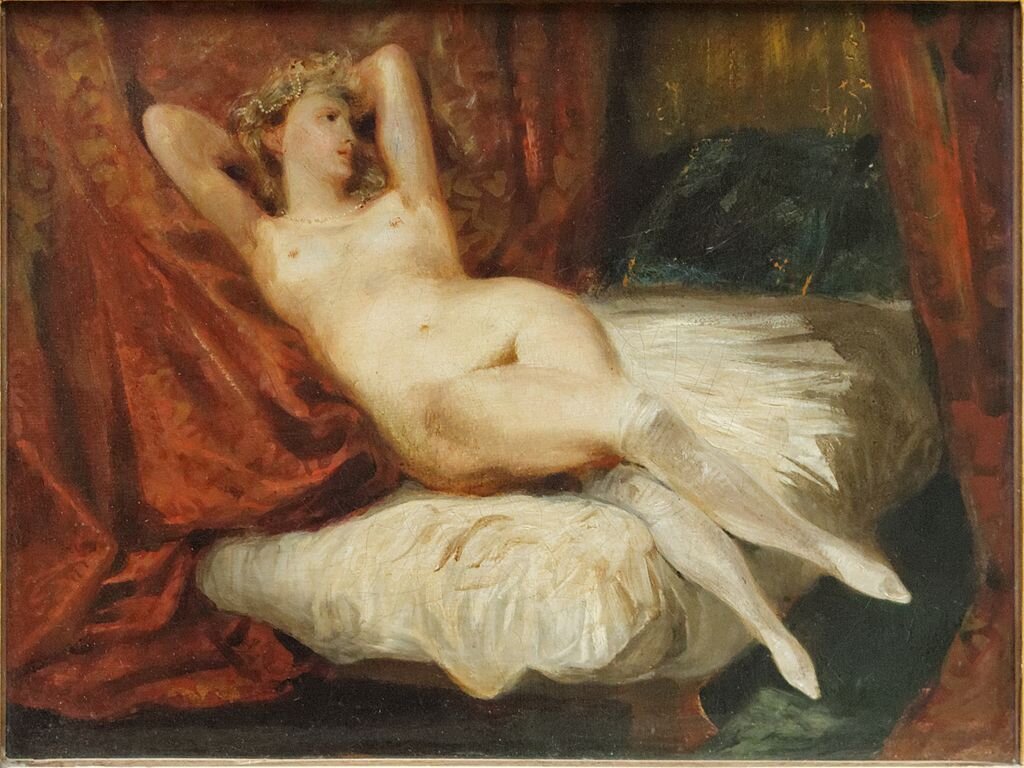

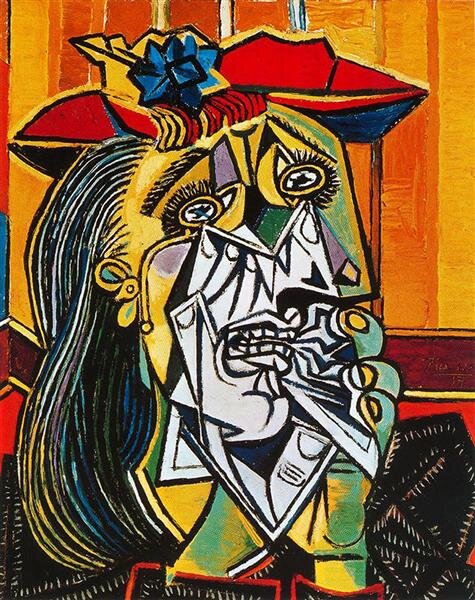

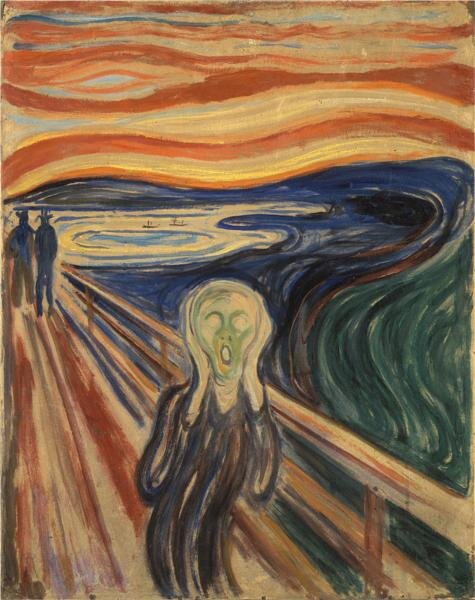

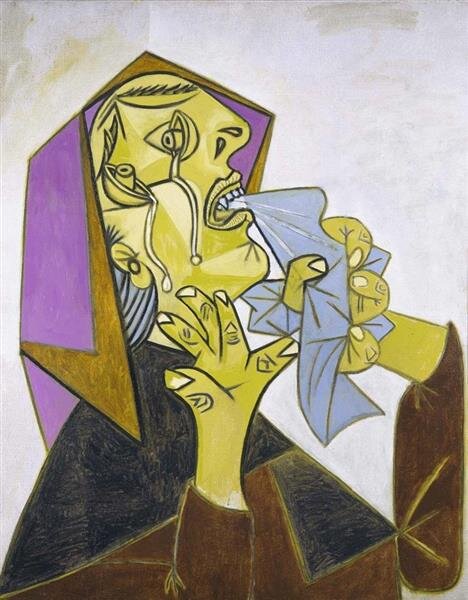

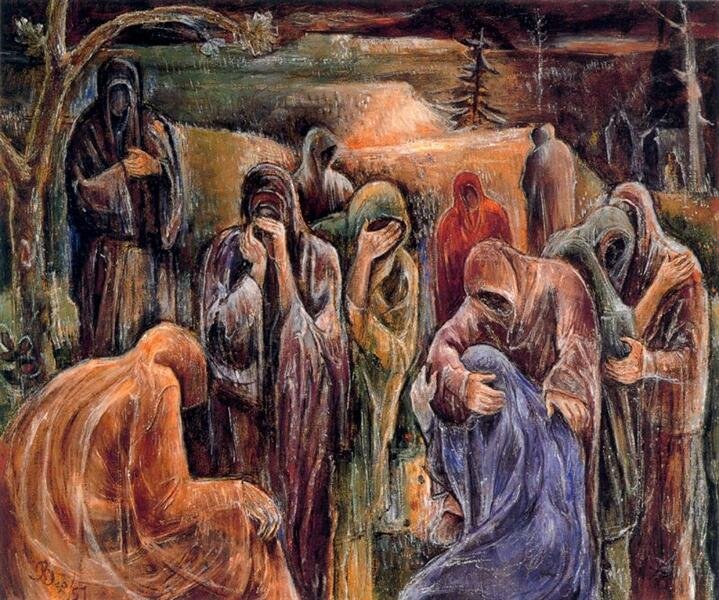

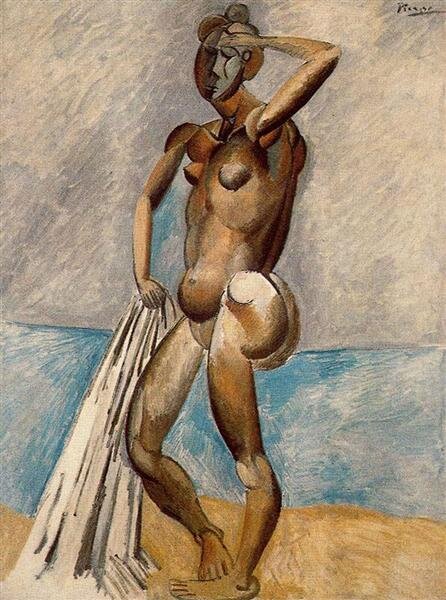

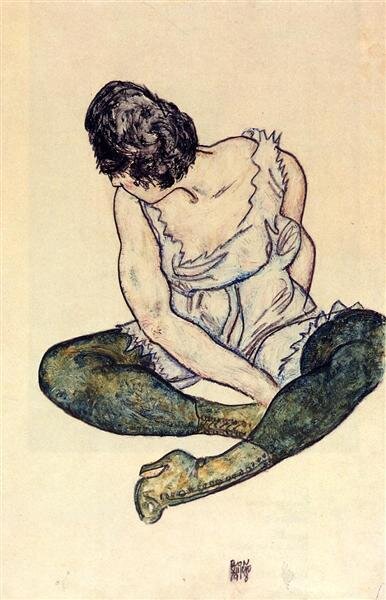

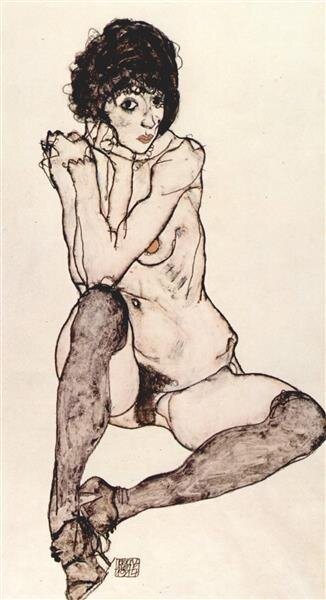

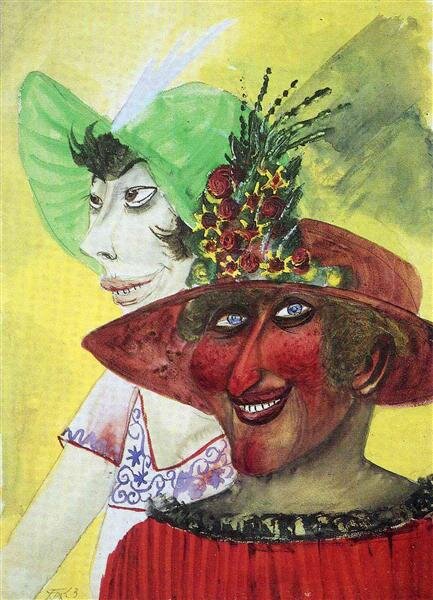

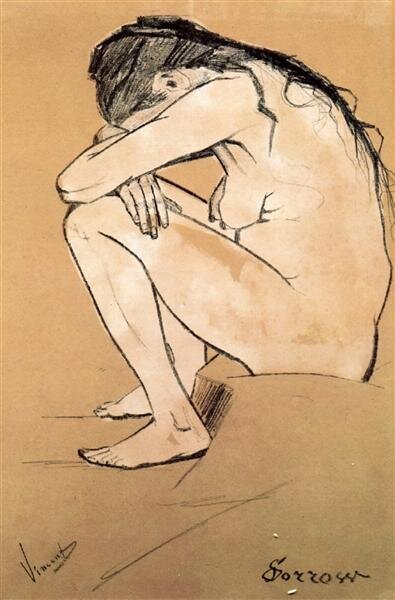

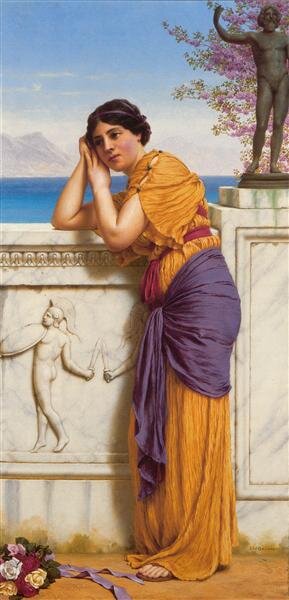

Connections & Contrasts with Women in Art

How do representations of women in art relate to and/or contribute to problems we encounter in society today?

triggered by #metoo . . . tintoretto . . . and medusa

yes — #metoo

Typically I never pay attention to trends, but I felt I had to put my hand up for this.

In all the years working with my project Parallel Lines — inviting and listening to stories from people of all ages, cultures and socio-economic backgrounds, all: triggered by my paintings and installations centred around a lone individual and a prison bed — I had resisted articulating my own experiences in words.

Doing so was really hard for me to do. And afterwards, for weeks, it was as though there was some sort of seismic shift going on inside of me. At times I wasn’t sure if my own demons might turn me to stone. So what happened?

the origins of the idea

I was in my studio, sketching.

I’d just returned from Italy, where I’d had a profound encounter with Bernini’s astounding sculpture: The Rape of Proserpina in the Borghese Gallery, Rome.

(I share this experience while discussing another painting in the series: Persephone Returned — Impressions of Rinelle Harper.)

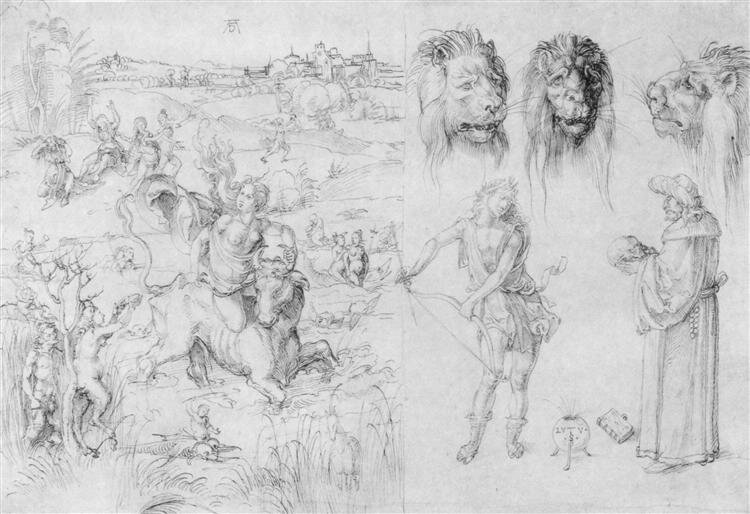

I was also fortunate to feel, at first hand, the magic of Caravaggio; and see a whole a series of exhibitions on the works of the Venetian painter — Tintoretto.

The Rape of Proserpina, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, 1622, Borghese Gallery, Rome

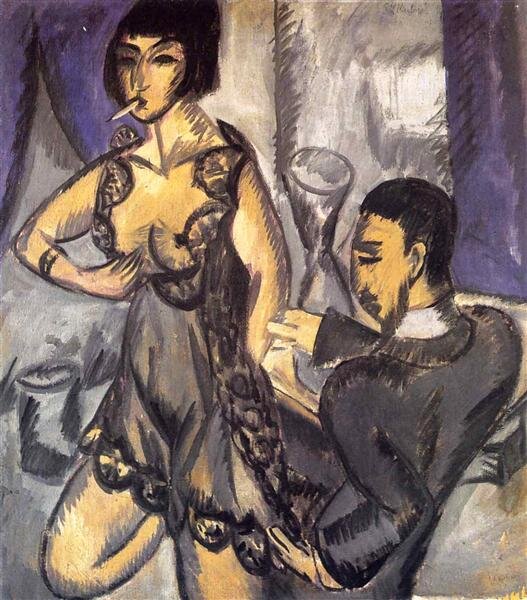

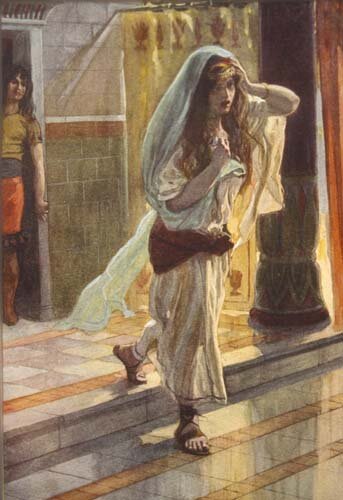

Susanna and the Elders, Tintoretto

Two of Tintoretto’s works particularly intrigued me:

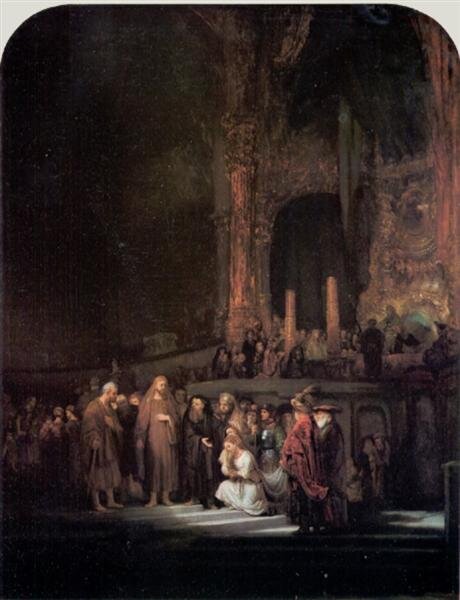

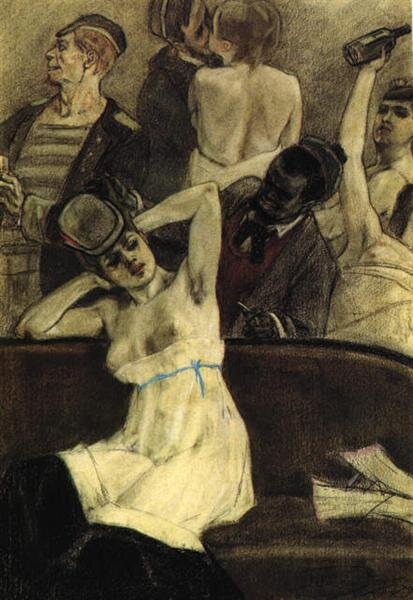

The first was Susana and the Elders — a biblical story about woman who is spied upon by a couple of old creeps who attempt to blackmail her and ruin her reputation . . .

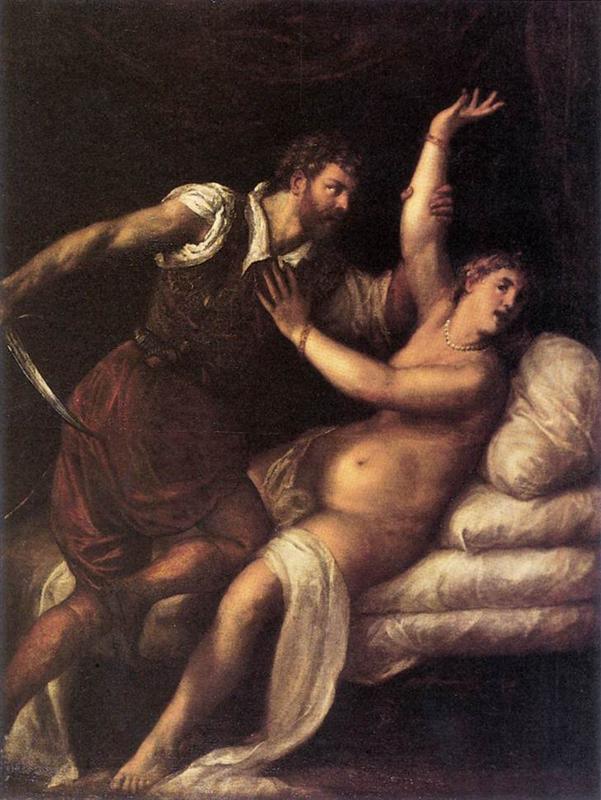

. . . and another work, Tarquin and Lucretia

— Lucretia is a Roman noblewoman who is attacked at night in her bedroom by a guest to her home — Sextus Tarquinius, the King’s son— and blackmailed into having sex with him. In the morning she tells her father and husband what happened and demands vengeance. While they’re deliberating what to do, Lucretia stabs herself in the heart and dies. Her death triggered a rebellion which overthrew the Roman monarchy and led to the foundation of the Republic of Rome.

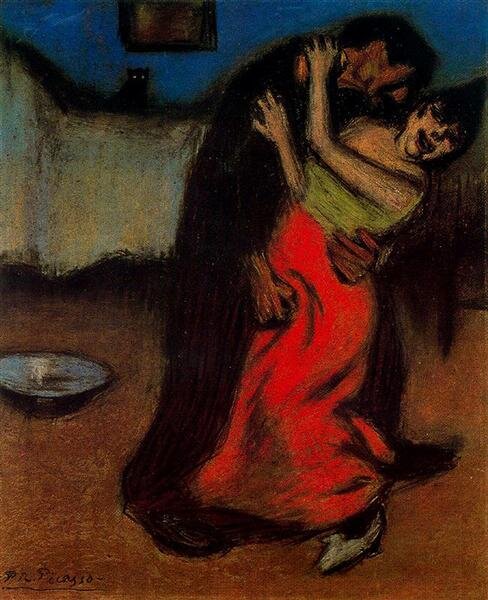

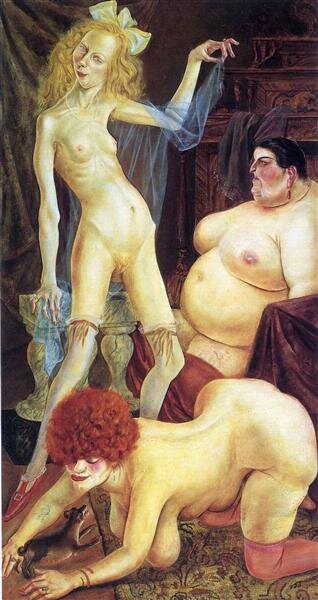

Both these stories reverberated in my own heart. They are also major themes in European art.

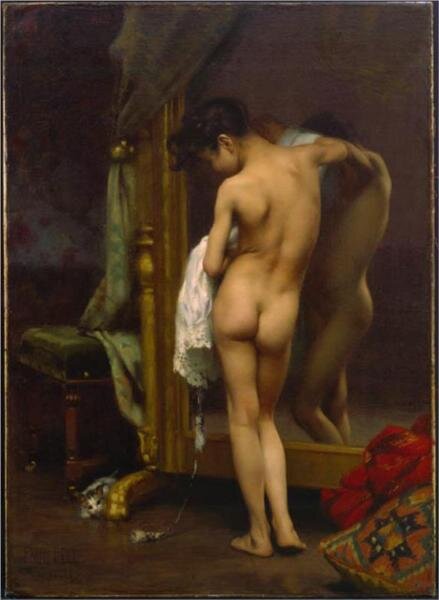

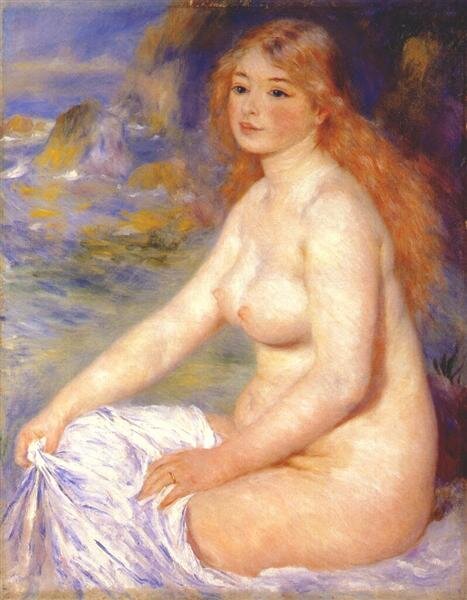

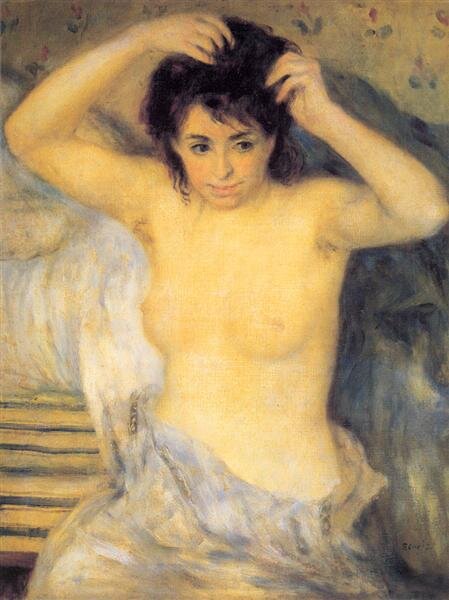

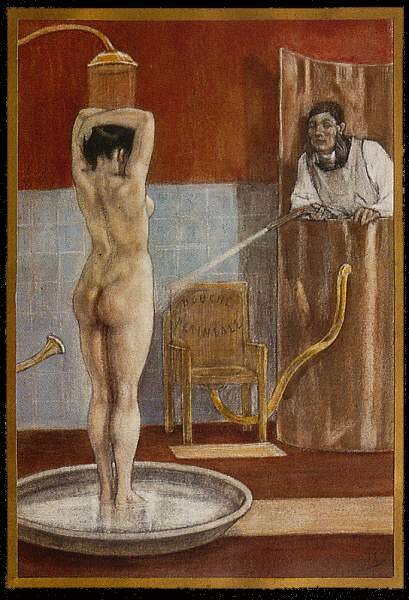

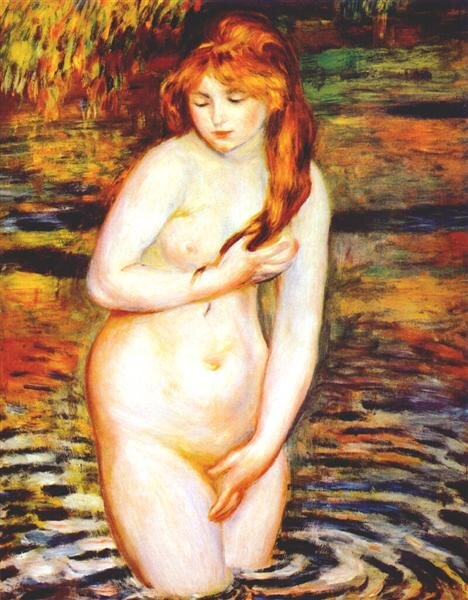

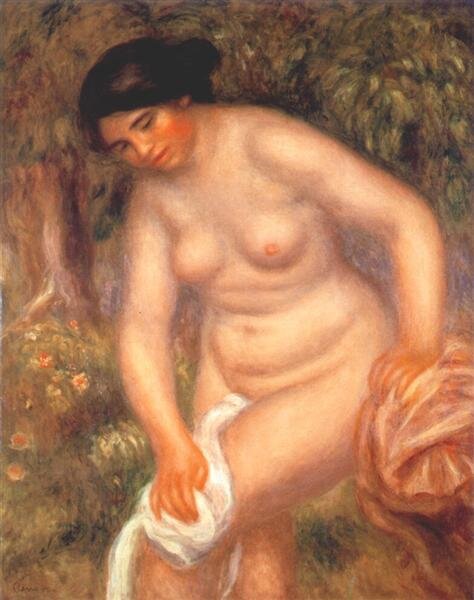

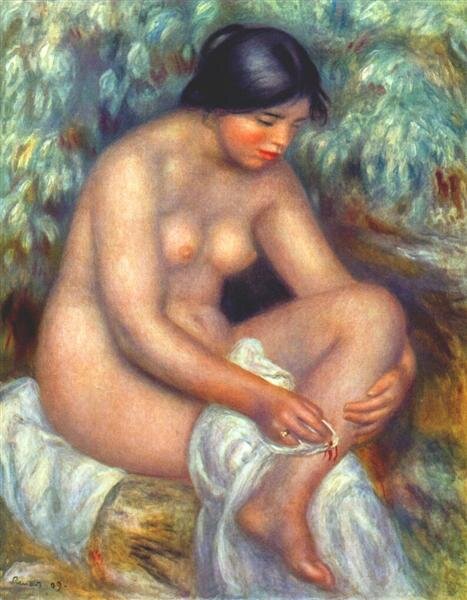

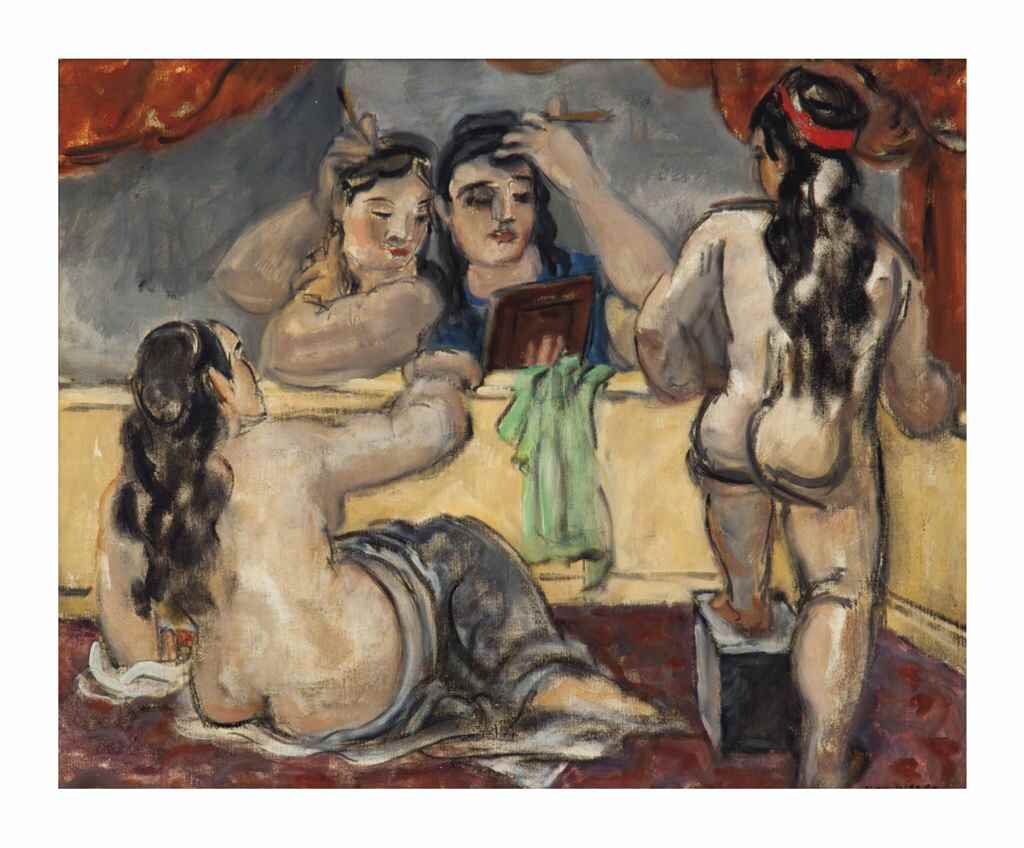

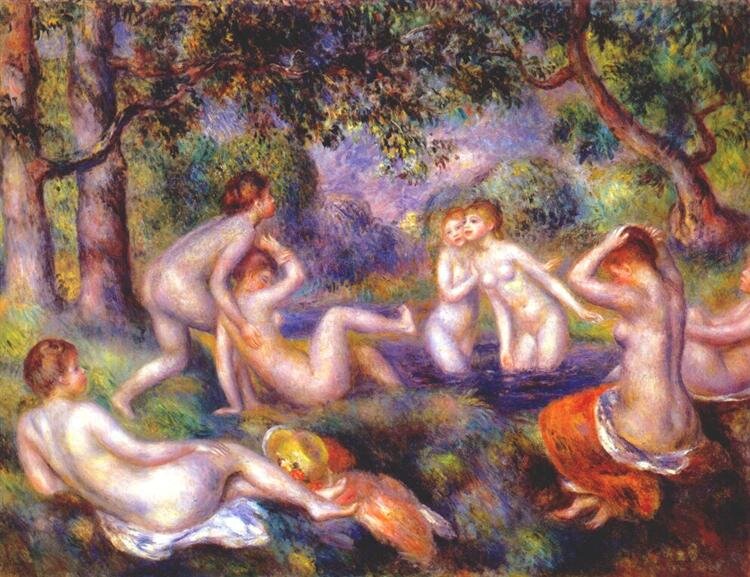

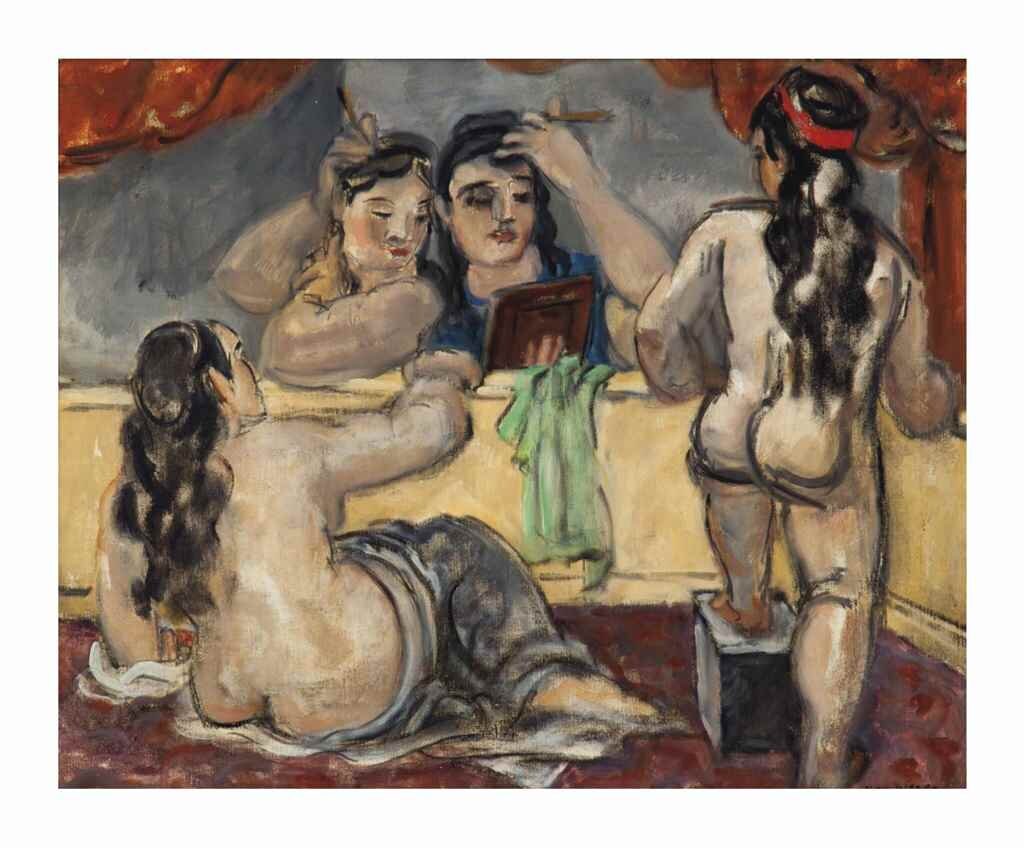

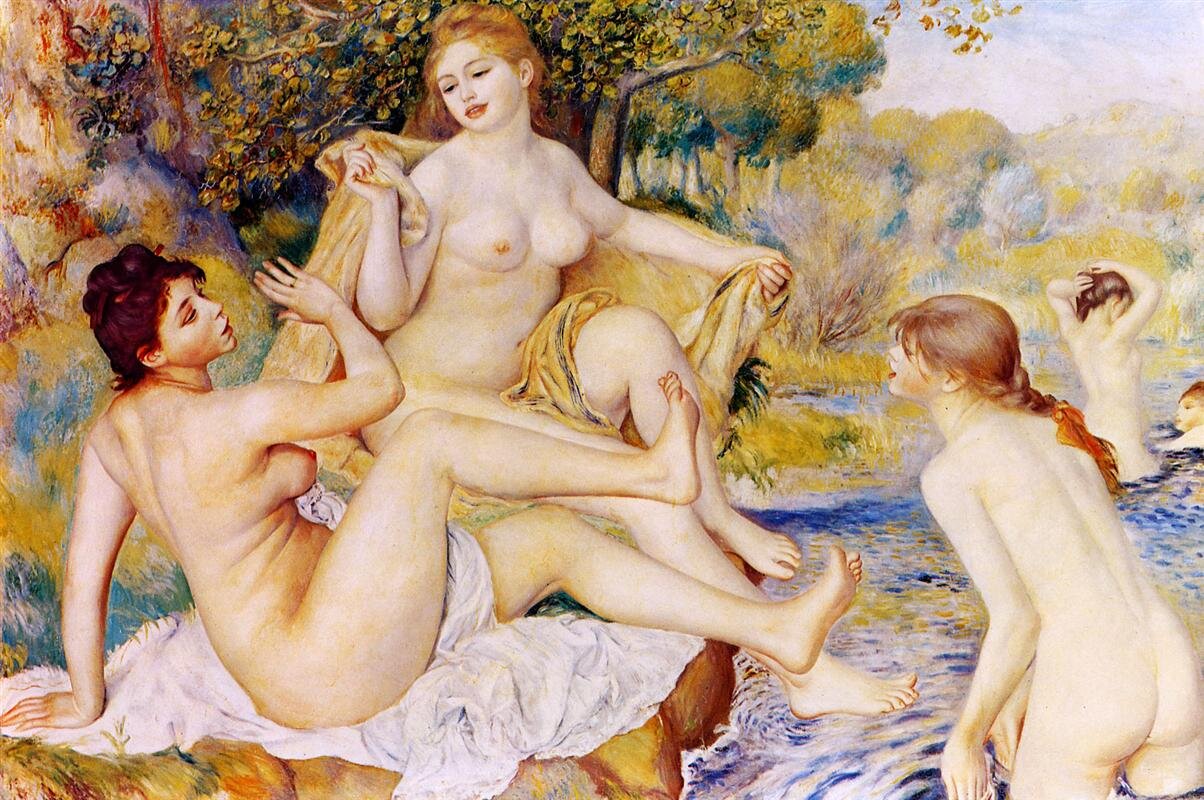

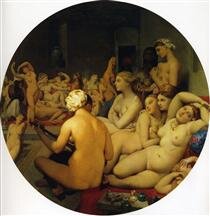

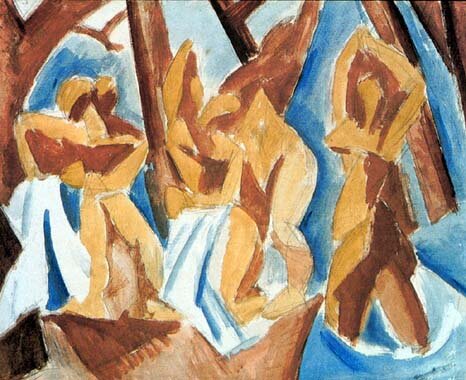

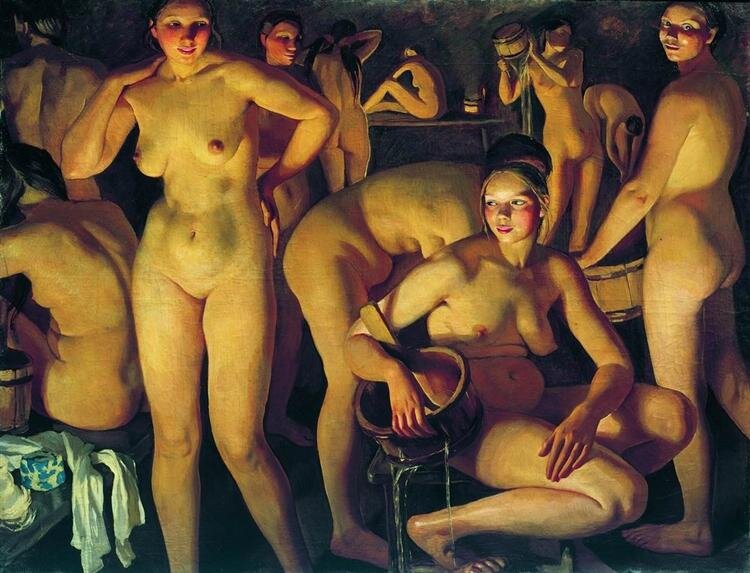

. . . click on links for examples of artworks depicting Women Being Watched While Bathing

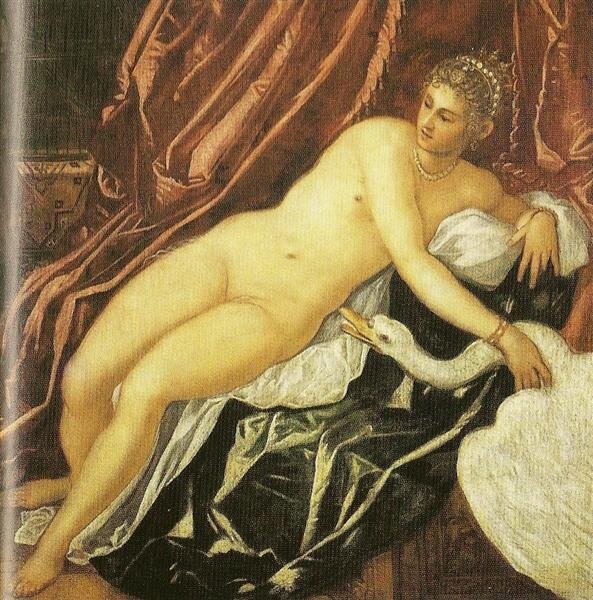

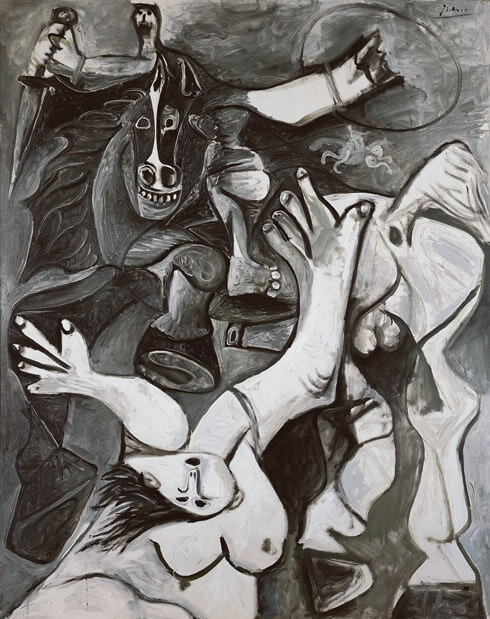

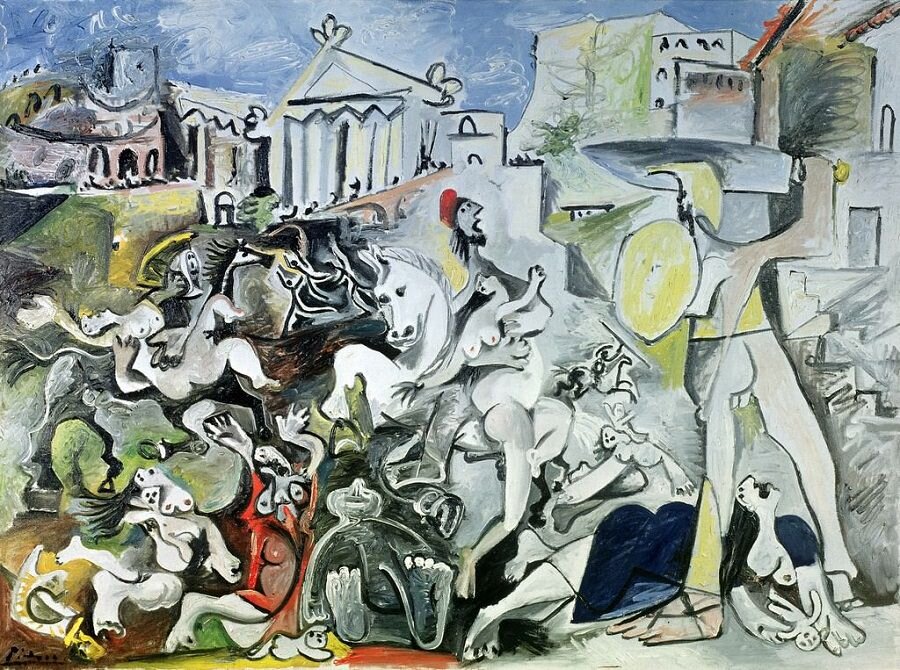

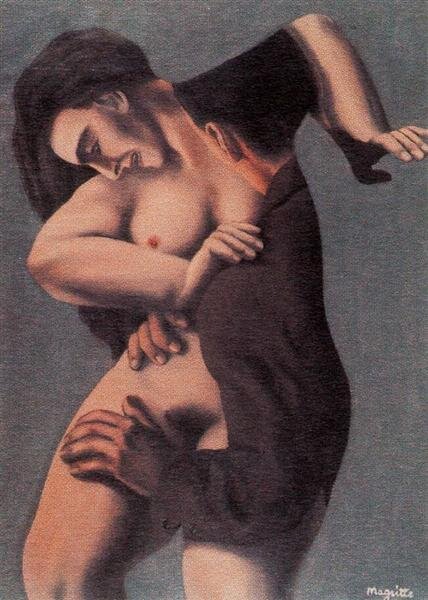

. . . click on links for examples of artworks depicting Women Being Raped

I decide to study Tintoretto’s work Tarquin and Lucretia . . . I start sketching out the work in pastels . . . (When you sketch artistic masterpieces you learn a great deal, often far more than you might anticipate — as I did here!)

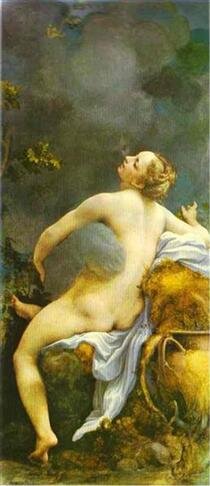

As a painter Tintoretto sought to combine the muscularity of Michaelangelo and colouring of Titian.

Summer, Jacopo Tintoretto, 1555, National Gallery of Art

Venice moment — Amanta Scott

He was also a master of light and shadow which I think stemmed from living in Venice.

You can’t help being struck by the dramatic contrasts of light and shadow, water and sky as you prowl those narrow twisty streets and canals.

The quality of light, particularly at dawn and at sunset, is absolutely enchanting. I’ve never seen anything like it.

Sunset in Venice — Amanta Scott

Tarquin and Lucretia, Tintoretto

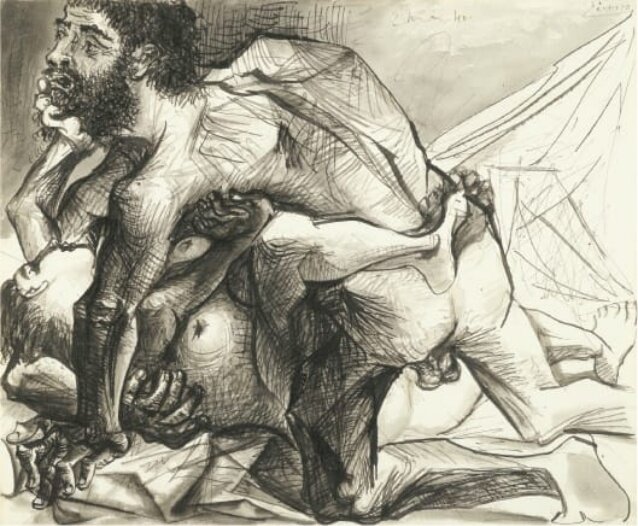

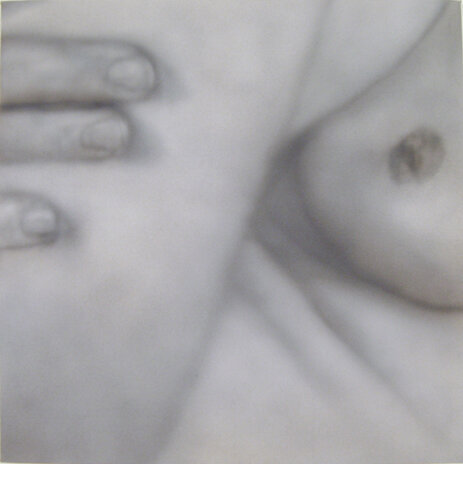

Looking at Tintoretto’s painting Tarquin and Lucretia we see: a violent struggle taking place... the falling pearls, the tumbling white cushion and broken bed post add to the urgency of the event, as does the dagger at her foot.

Now notice how all the lines in the painting converge on one point in the work: Tarquin’s hand — which is almost invisible, hardly painted at all, basically blocked in — pulling at the flimsy fabric covering Lucretia’s body.

For me this unknown element heightens the element of fear. Contrast this with the amazing detail of Lucretia’s hand, in front of this point — the flexed fingers and palm seem to push everything away, including ourselves as viewers and witnesses.

However, it was while I was sketching in Tarquin’s left hand around her throat, that I became aware of the expression on her face. And that stopped me cold.

Notice how her expression is completely blank, almost passive.

In a flash, I recalled asking my doctor why I hadn’t fought back, and she replied: “Most don’t” - and turned away.

Then I become aware of just how horrible I’m feeling while sketching this work.

I realize: I can’t continue this.

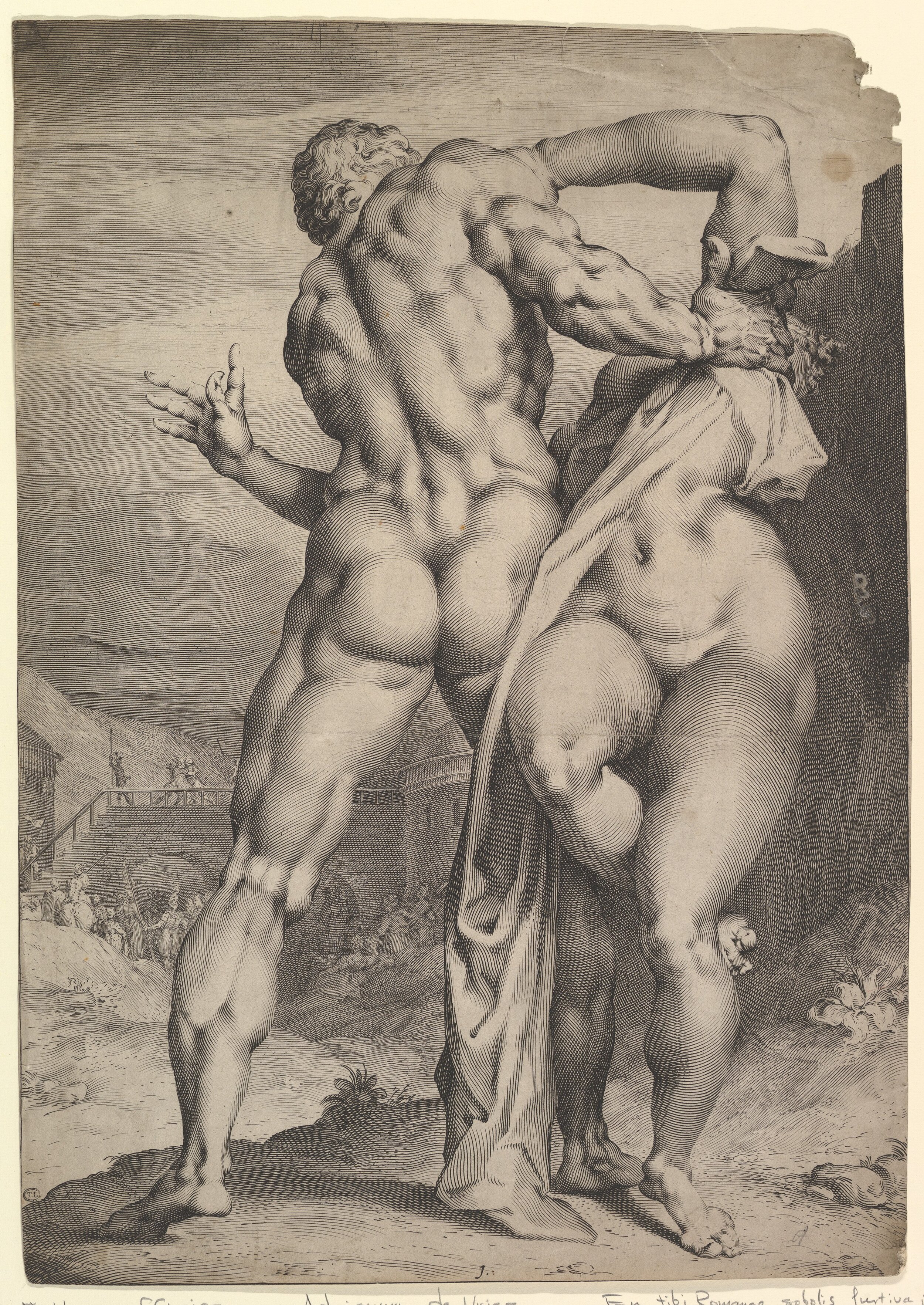

The Rape of a Sabine Woman by Giambologna, Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence

I wonder: What would possess anyone to paint or sculpt such a horrible situation?

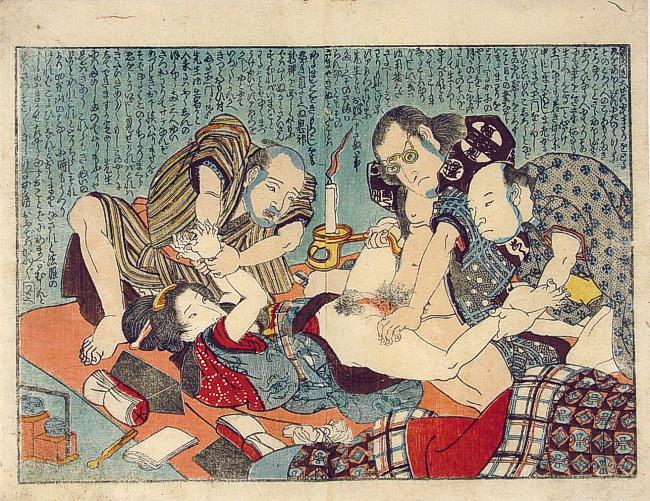

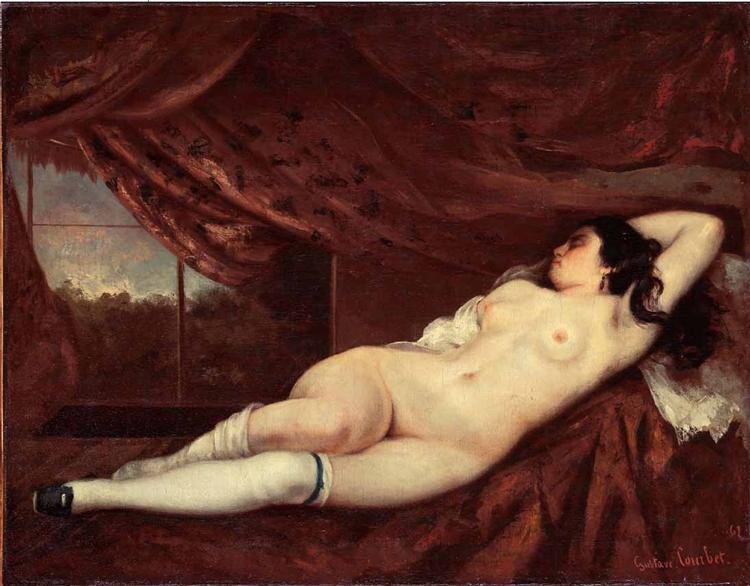

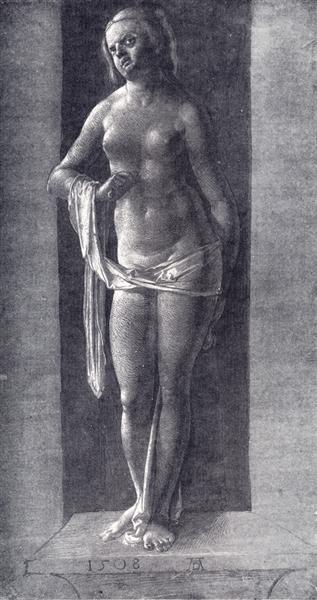

Why are there so many artworks dedicated to rape?

When you consider the time it takes to create an artwork, that’s an amazing amount of energy going into one specific subject.

What is wrong with us that we continually focus on violation?

The idea that women are merely vessels for sexual desire has enabled enslavement, rape, forced reproduction, and other forms of sexual coercion.

I’m always amazed when people try to justify rape historically claiming that women were needed to repopulate cities.

Tell me we’re not going to justify rape now just because hundreds of thousands of people are dying of starvation and covid19.

I ask myself: If energy goes where attention is directed, why feed into more of the same?

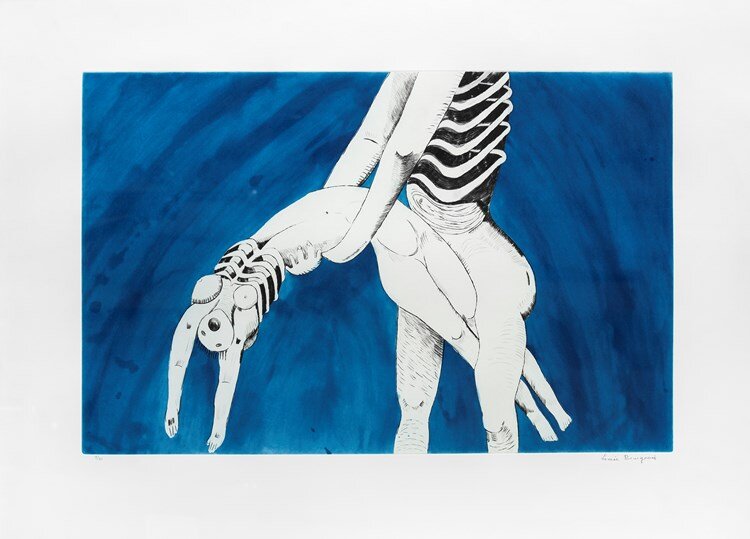

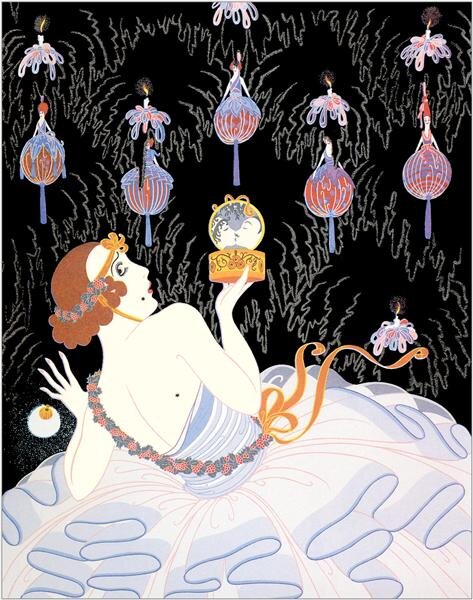

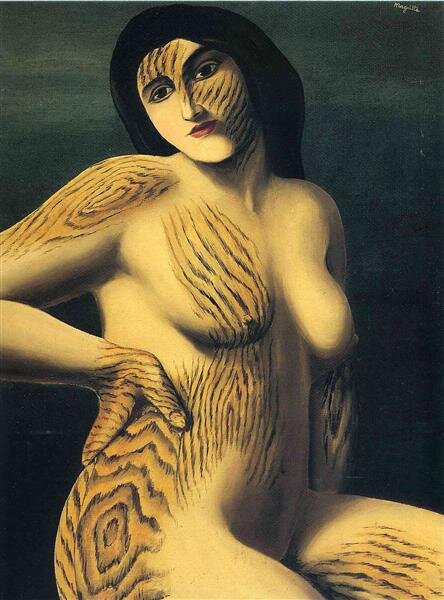

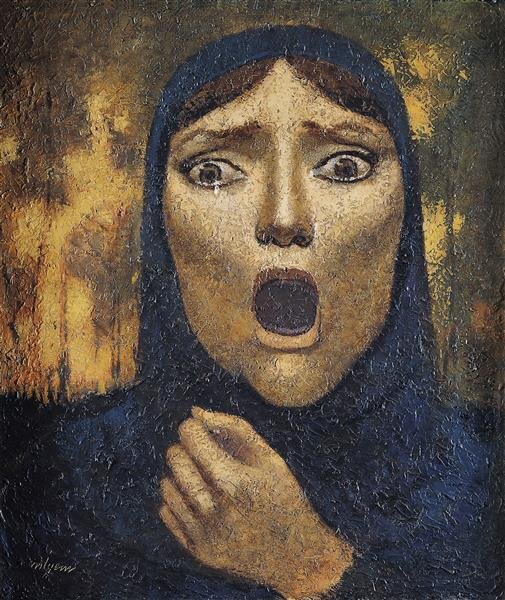

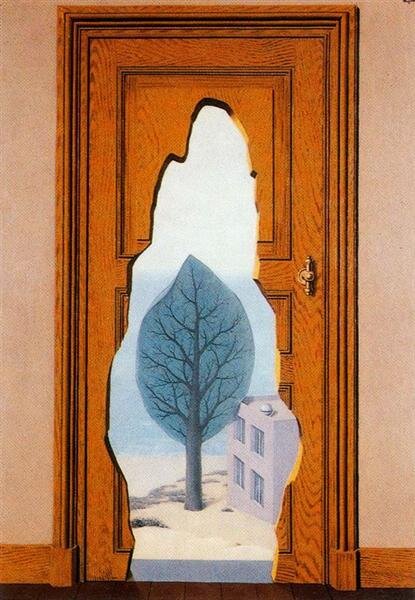

I think: I need to go at this completely differently. Rather than re-telling or reinterpreting the myths, scriptures, stories and artworks of the old masters I need to change the game entirely. Instead of presenting women as victims, I need to start celebrating women as survivors, wise and willful, brave, insightful, determined, strong, fierce, compassionate and kind.

And this is what started me on the route to my project Eyeing Medusa.

What about Tarana Burke?

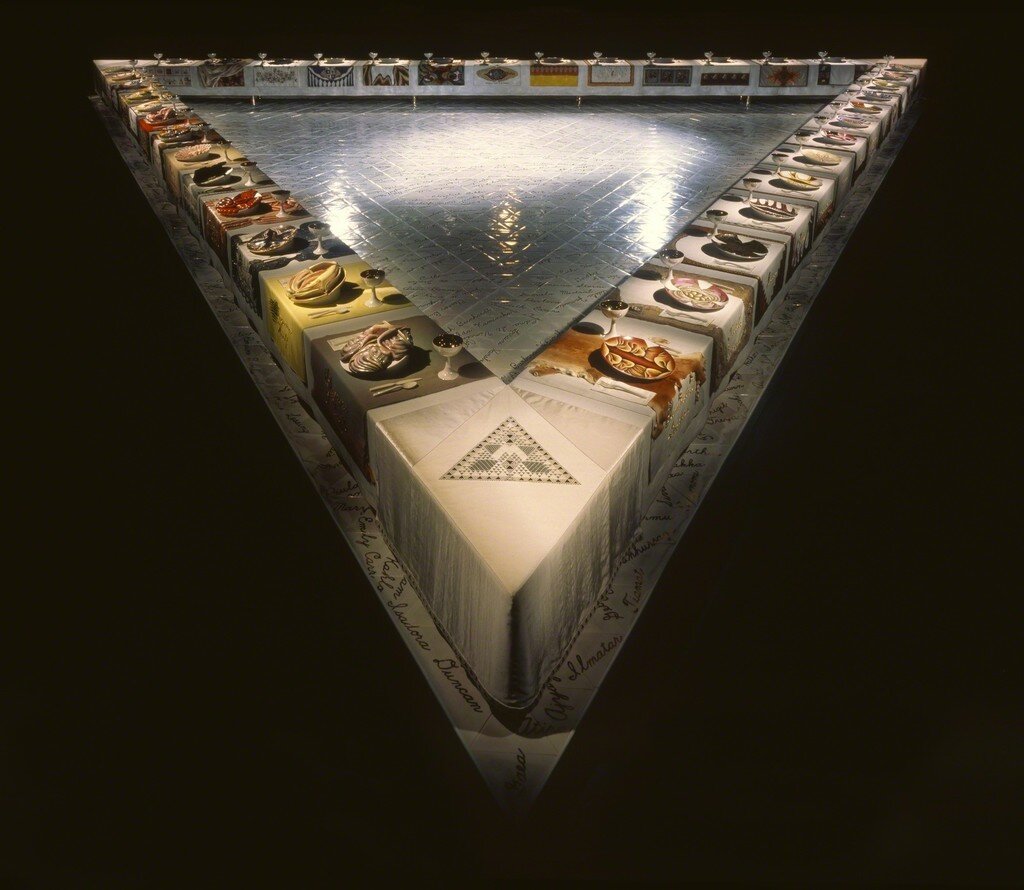

One of the first women I knew I had to paint was Tarana Burke — an African-American civil rights activist from The Bronx, New York who started the #MeToo movement.

Tarana Burke grew up in a low-income, working-class family in a housing project. She was raped and sexually assaulted both as a child and a teenager. Thanks to her mother’s support and encouragement, she started to improve the lives of young girls living in marginalized communities, recognizing that many of them undergo extreme hardships.

I attended one of her talks, where she spoke about comforting a young girl who’d been raped. Recalling the moment when she said: “I know how you feel — that happened to me too.” she told us that this was the moment that prompted her to begin using the phrase "Me Too".

In 2017, following the use of #MeToo as a hashtag, the "Me Too" movement became a global phenomenon that raised awareness about sexual harassment, abuse, and assault in society.

Tarana Burke emphasized that while the MeToo movement has helped many women with a similar experience stand up for themselves, the movement was intended for women of colour from low income communities.

This made me stop and think. For a moment I felt rejected, cast out of something I’d only just connected with, but I realized that regardless of anything that has happened to me or my ancestors, I still have to recognize how privileged I am.

Personally, I don’t have to worry about myself or my children being shot dead while going for a run or pulled over in a car because of the colour of my skin. But my friends do. So that’s why I painted the work Black Lives Matter — Impressions of Patrisse Cullors.

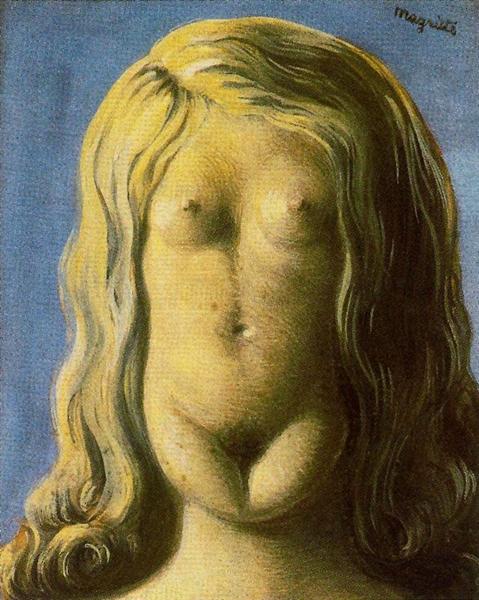

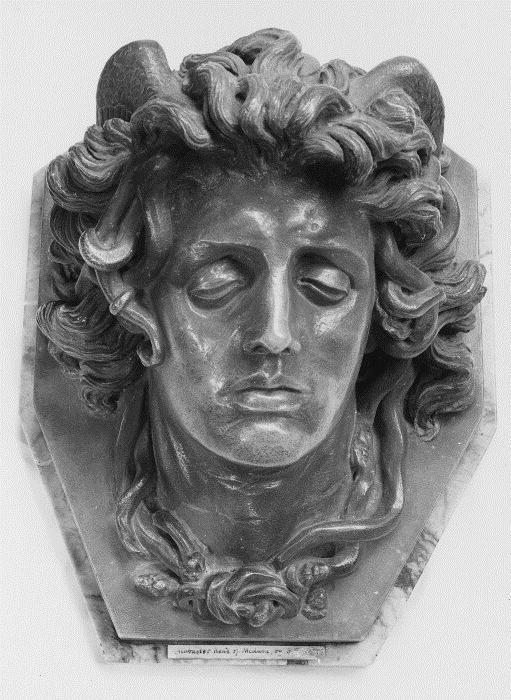

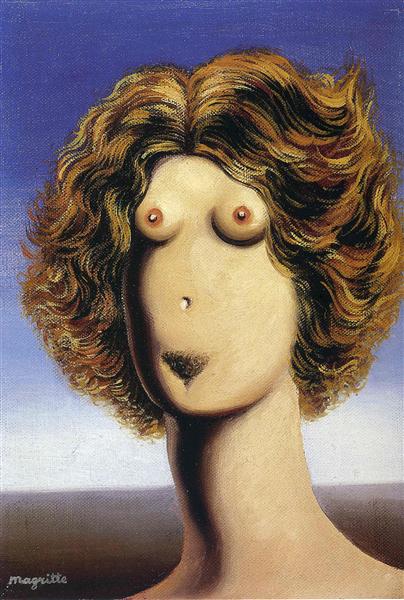

Today Medusa is largely known as a hideous female monster with snakes for hair whose fury and frightful eyes will turn viewers to stone if they so much as glance at her. The face of Medusa appears in paintings and sculptures throughout history; in literature, film and theatre; on boats and buildings; on housewares; and even as a logo by the fashion company Versace.

The archetypal “angry woman”, Medusa has been adopted as a symbol of female rage, and the personification of female fury.

“The story of a powerful woman raped, demonized, then slain by a patriarchal society [. . .] seems less of an ancient myth than a modern reality. [. . .] the way Medusa has resurfaced in recent election cycles also points to the pervasiveness of misogyny: Angela Merkel, Theresa May, and Hillary Clinton have all received the Medusa treatment lately, their features superimposed onto bloody, severed heads.”

Perseus with the Head of Medusa, in the Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence — photo by Paolo Villa

According to Art historian Christine Corretti, the artist Cellini believed Medusa symbolized both the threat of women’s burgeoning political power and a feminized Italy.

Benvenuto Cellini's Perseus and Medusa symbolizes the male ruler overcoming a female adversary. Dr. Corretti argues that although not a surrogate for powerful Medici women, Cellini's Medusa may have reminded viewers that Cosimo I de' Medici's power stemmed in part from maternal influence.

Drawing upon a vast body of art and literature, Dr. Corretti concludes that Cellini and his contemporaries knew the Gorgon as a version of the Earth Mother.

Tarana Burke

#MeToo

Tarana Burke (b. September 12, 1973) is an African-American civil rights activist from The Bronx, New York.

She founded the “Me Too” movement in 2006 which blossomed into a worldwide campaign to raise awareness about sexual harassment, abuse, and assault in society.

In 2006, Burke began using the phrase "Me Too" to raise awareness of the pervasiveness of sexual abuse and assault in society, and the phrase developed into a broader movement, following the 2017 use of #MeToo as a hashtag.

In 2017 the "Me Too" movement, became a global phenomenon that raised awareness about sexual harassment, abuse, and assault in society.

For additional interesting reading see: rape victim turned into a monster

In 2017 Burke and other influential female activists were named "the silence breakers" by Time magazine. She currently serves at the Girls for Gender Equity in Brooklyn as its senior director.

digging deeper into Medusa’s story. . .

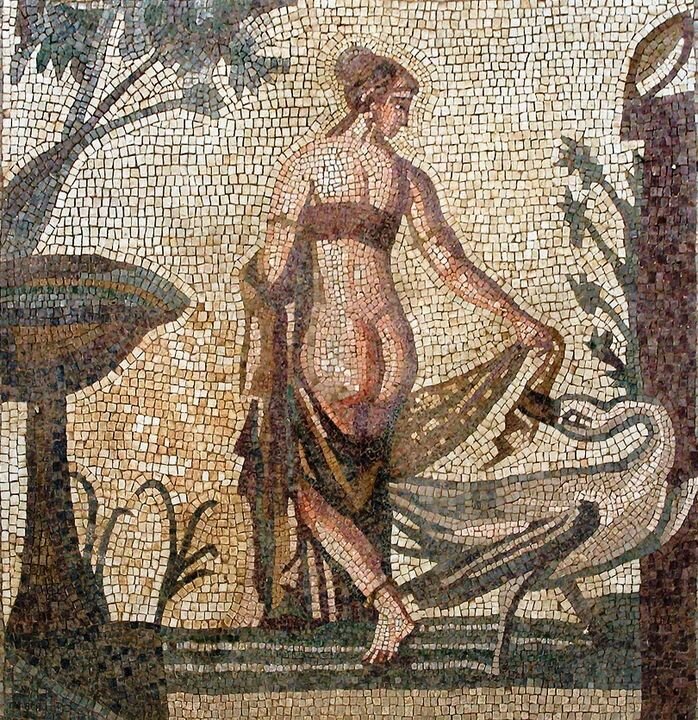

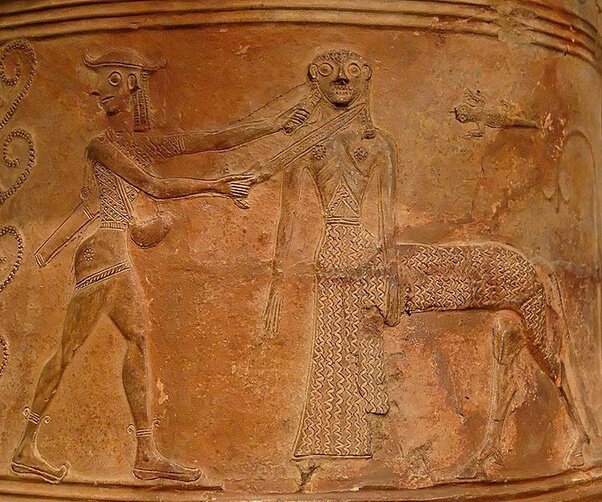

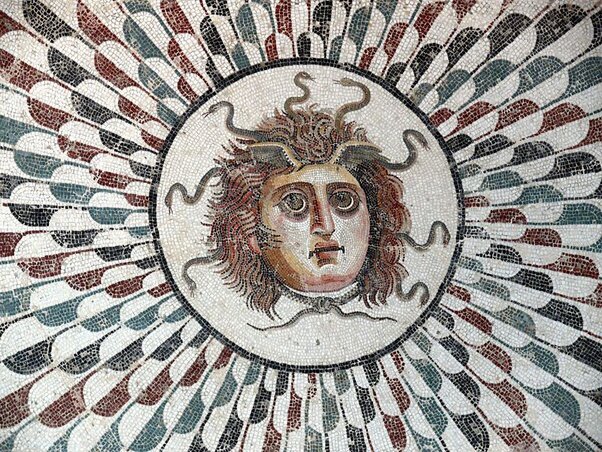

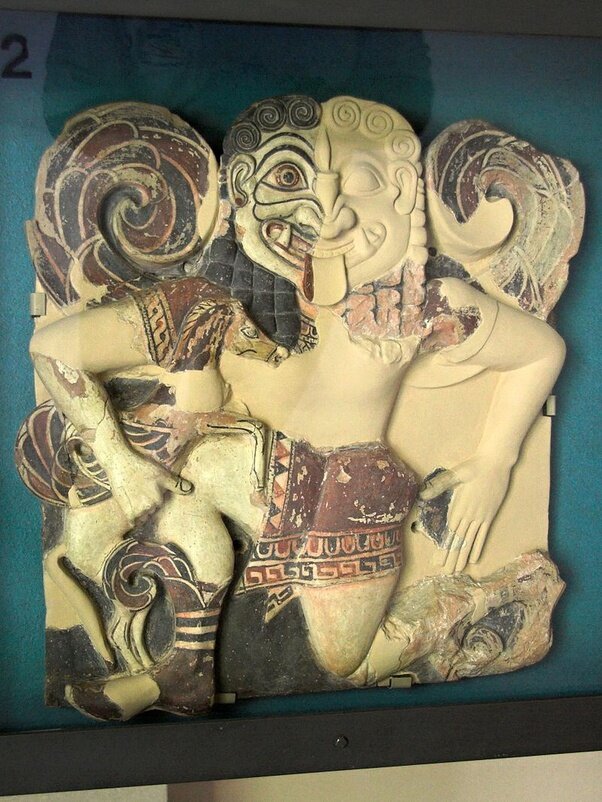

A Gorgon

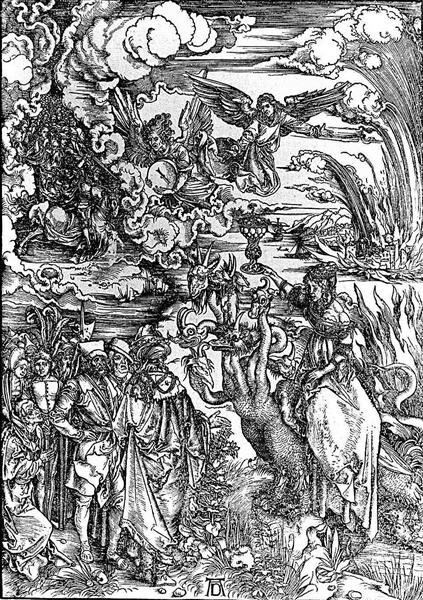

The Gorgon was a protective deity from the ancient world. The temples of the Oracles were protected by and frequently associated with serpents and Gorgons. A Gorgon wore a belt of serpents that intertwined as a clasp.

An archaic Gorgon (circa 580 BC), as depicted on a pediment from the temple of Artemis in Corfu, Archaeological Museum of Corfu

image: Wikipedia

The Caduceus, symbol of God Ningishzida, on the libation vase of Sumerian ruler Gudea, circa 2100 BCE.

image: Wikipedia

The image of two serpents entwined around an axial rod may also be the origins of the caduceus, which first appeared as a symbol of God/Goddess Ningishzida, a Mesopotamian underworld deity considered to be the god or goddess of medicine, nature and fertility.

The power of a Gorgon was so strong that one would be turned to stone upon daring to gaze at her. Such images were therefore used for protection and put upon a range of items, including temples, armour, shields and wine vessels.

Detail from Alexander and Bucephalus - Battle of Issus mosaic - Museo Archeologico Nazionale - Naples. Image courtesy of Wikipedia

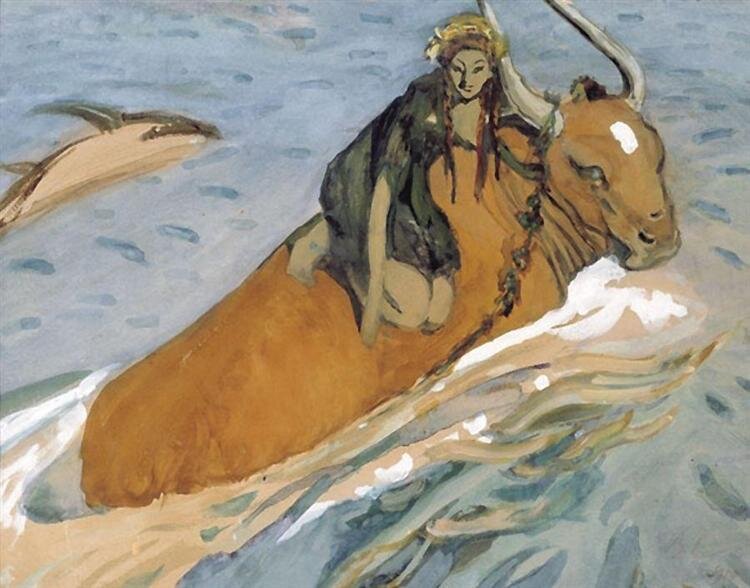

The oldest existing version of the story of Medusa comes from the poem Theogonia, composed circa the eighth century BCE by the Greek poet Hesiodos of Askre. Here, Hesiodos mentions that Medusa was the only mortal of three sisters, daughters of the ancient marine deities Phorcys and Ceto, chthonic monsters from the archaic world. In this version she is born a Gorgon with the ability to turn people to stone at a glance. She may also, according to some depictions, have had the body of a horse.

Hesiodos writes: “With her lay the Dark-haired One [i.e., Neptune/Poseidon] in a soft meadow amid spring flowers.” Since Hesiodos makes no mention of this being a rape, we may understand that she was a willing partner in sexual activity. She was, however, still cursed and punished as a result.

In 8 AD the Roman poet Ovid wrote a Latin narrative poem entitled The Metamorphoses (Latin: Metamorphōseōn librī: "Books of Transformations") comprising 11,995 lines, 15 books and over 250 myths, which chronicled the history of the world from its creation to the deification of Julius Caesar.

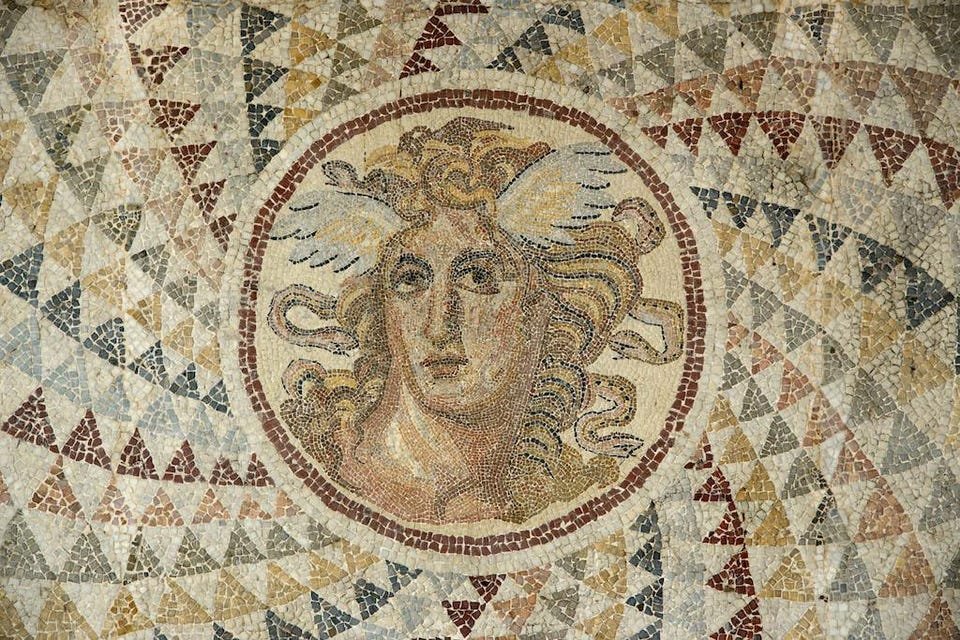

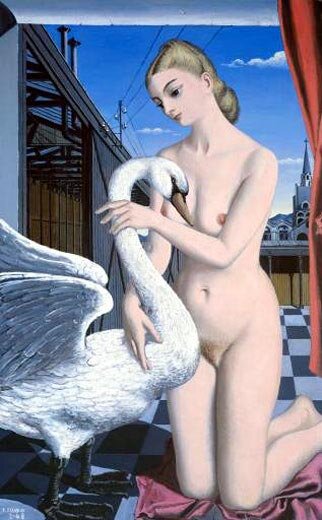

In Ovid’s version, Medusa was once a beautiful young maiden, the only mortal of three sisters (Medusa, Stheno and Euryale) known as the Gorgons, who were also sisters of the Graeae: Deino, Pemphredo and Enyo — old women, grey ones, grey witches — who shared one eye and one tooth between them.

Perseus Returning the Eye of the Graii, Henry Fuseli, image courtesy of Wikipedia

Being mortal, Medusa was also distinguished from them by the fact that she alone was born with a beautiful face. Ovid especially praises the glory of her hair, “most wonderful of all her charms.”

Medusa was one of the sacred priestesses serving in the Temple of Athena. Some say she had many suitors but had chosen not to marry in order to devote herself to her work. Rumour had it that her beauty rivalled that of (and may have angered) Athena, but that was short-lived.

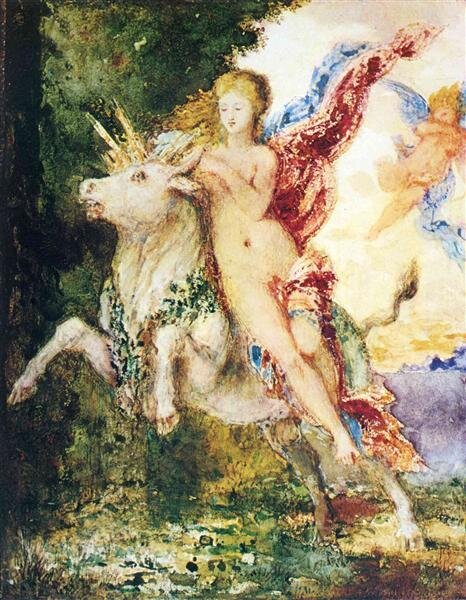

One day Medusa’s beauty caught the eye of the sea god Poseidon/Neptune, who became enamoured with the lovely girl. Determined to have her at any cost, he raped her in the sacred temple of Athena/Minerva.

Furious at the desecration of her temple, Athena/Minerva punishes the victim rather than the perpetrator. She transforms Medusa into a monster with a face so hideous and a gaze so piercing that now, instead of inspiring desire, the mere sight of her is sufficient to turn a man to stone. Medusa’s beautiful hair is transformed into a coil of writing serpents; and she is banished to a remote and foreign land.

Soon after this, Polydectes, the king of Seriphos, sends Perseus on a quest to bring back the head of Medusa. (The king fully expects and hopes that Perseus will be unsuccessful because he wants to marry Perseus’ mother, Danaë, and requires her son be otherwise occupied.)

Aided by Hermes and Athena, Perseus pressed the Graeae, sisters of the Gorgons, into helping him by seizing the one eye and one tooth that the sisters shared and not returning them until they divulged Medusa’s whereabouts.

Perseus and the Graeae by Edward Burne-Jones (1892), image courtesy of Wikipedia

He also forced them to provide him with winged sandals (which enabled him to fly), the cap of Hades (which conferred invisibility), a curved sword, or sickle, to decapitate Medusa, and a bag in which to conceal the head.

Perseus finally reaches the fabled land of the Gorgons, located either in the far west, beyond the outer Ocean, or in the midst of it, on the rocky island of Sarpedon.

Perseus creeps up on Medusa while she is asleep. Then — using the reflection in Athena’s bronze shield as a guide so as to not look directly at Medusa and be turned into stone — Perseus decapitates Medusa with his sickle.

At the time of her death Medusa was pregnant by Poseidon. The assassination of Medusa releases her two unborn children Chrysaor and Pegasus (the winged horse) from her severed neck. The resulting noise awakens the Gorgon sisters who endeavour to avenge Medusa’s death but they are unsuccessful because Perseus is wearing Hades’ Cap of Invisibility and Hermes’ winged sandals. Returning to their cave the sisters mourn their fallen sister. Hearing their gloomy lament it is said that Athena modelled the music of the double pipe, the aulos, after the sound.

On the way back to Seriphos, flying across northwest Africa, Perseus stopps briefly in Ethiopia. There, he rescues and weds his future wife, the lovely princess Andromeda who he found naked and chained to a rock on the shore. (Save that for another story). The corals of the Red Sea were said to have been formed as Medusa's blood spilled onto seaweed when Perseus laid down her severed head beside the shore — attending to Andromeda’s rescue.

Later as Perseus flies across the sands of Libya, with Medusa’s putrefying head clutched in his hands, the falling drops of her blood create a race of poisonous vipers of the Sahara; and also spawn the Amphisbaena (a horned dragon-like creature with a snake-headed tail). And that is why that, to this day, Libya abounds with serpents.

Perseus then flew to Seriphos, where his mother was being forced into marriage with the king, Polydectes. Perseus used Medusa’s head to turn him and various other vicious islanders into stone — which explains why the island became famous for its many rocks.

Perseus then gave Medusa's head to Athena, who placed it on her shield, known as the Aegis.

Athena also collected some of the remaining blood and gives most of it to Asclepius, who used the blood from Medusa’s left side to take people’s lives and the blood from her right side to raise people from the dead. The rest of Medusa’s blood – a vial containing two drops – Athena gave to her adopted son, Erichthonius; Euripides says that one of the drops was a cure-all, and the other one a deadly poison. She also put aside, in a bronze jar, a lock of Medusa’s hair for Heracles, who subsequently gave it to Cepheus’ daughter, Sterope, to use to protect her hometown Tegea. Although the lock of hair lacked the power of Medusa’s gaze, it could still cast terror into any enemy unfortunate enough to behold it, accidentally or otherwise.

the roots go deeper

When considered within an historical context, however, one wonders if the roots of the story might go much deeper.

Greek historian Herodotos of Halikarnassos (c. 484 – c. 425 BCE) wrote in Histories 2.91 that Medusa and her sisters lived in the land of Libya, which, for the ancient Greeks, meant the whole part of North Africa west of Egypt.

There is reason to wonder if the origins of the character Medusa may be rooted in the Egyptian Cobra Goddess Wadjet or the Minoan Snake Goddess. Depicted as a snake-headed woman or a cobra she was associated with the land as matron and protector of Egypt; of kings and of women in childbirth. As the nurse of the infant God Horus, Wadjet was closely associated with the Eye of Ra. The word “Egypt” comes from the Greek word for “Black”, referring to the Black Nile, but possibly also referring to the people. Her serpentine hair may have been dreadlocs.

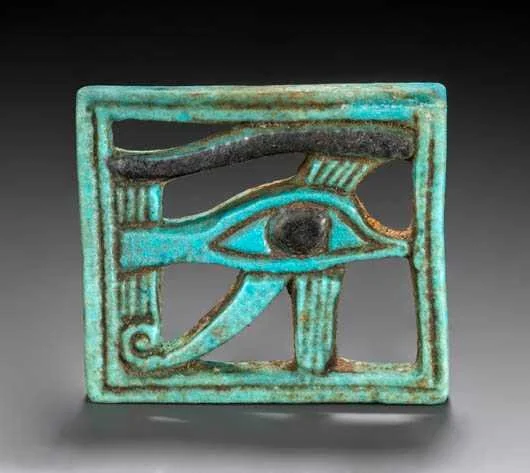

Wedjat Eye, Egyptian Amulet, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

Could this fear of Medusa stem from the fear of unknown people of colour?

About the #MeToo Movement and its impact in Canada

Resources from #MeToo Movement

References

- New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology, Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd., New York, 1959

- Ancient Mirrors of Womanhood, Merlin Stone, Beacon Press, Boston, 1984

- When God Was A Woman, Merlin Stone, Harvest Edition, 1976

- The Civilization of the Goddess, The World of Old Europe, Marija Gimbutas, HarperCollins Publishers, 1991

- The Language of the Goddess, Marija Gimbutas, HarperRow publishers, San Francisco, 1989

- Cellini's Perseus and Medusa and the Loggia dei Lanzi: Configurations of the Body of State, Christine Corretti, Ph.D., Brill, 2015

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wadjet

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perseus

- https://www.greekmythology.com/Myths/Creatures/Medusa/medusa.html

- http://employees.oneonta.edu/farberas/arth/arth200/Body/snake_goddess.htm

- http://arthistoryresources.net/snakegoddess/votary.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Snake_worship

- https://commons.wikimedia.org

- https://guts4garters.wordpress.com/2009/05/25/the-angry-woman-feminism-medussa/

- https://talesoftimesforgotten.com/2020/10/10/where-does-the-myth-of-medusa-come-from/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caduceus

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gorgon

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Graeae

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Burne-Jones

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Egyptian_hypothesis

- http://arthistoryresources.net/snakegoddess/

- https://rbgstreetscholar.wordpress.com/2007/ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Summer_A21762.jpg11/24/black-egyptians-the-original-settlers-of-kemet/

- https://www.mbam.qc.ca/en/collections/arts-of-one-world

- https://religion.wikia.org/wiki/Ningishzida

- https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2016/11/the-original-nasty-woman-of-classical-myth/506591/

- https://www.vice.com/en/article/qvxwax/medusa-greek-myth-rape-victim-turned-into-a-monster

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perseus_with_the_Head_of_Medusa

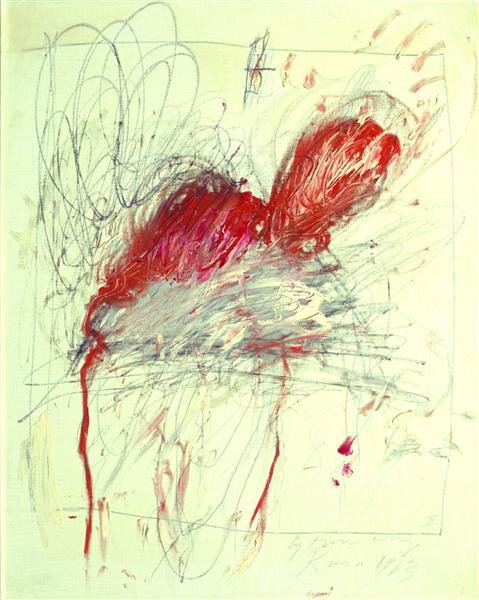

Amanta Scott, encaustic on canvas on cradled panel, Eyeing Medusa series, 108.5 x 108.5 x 5.75 cm, 2019-2021. Read more